Brazil is on the verge of a coffee shortage, and that could be bad news for the quality of your morning caffeine fix.

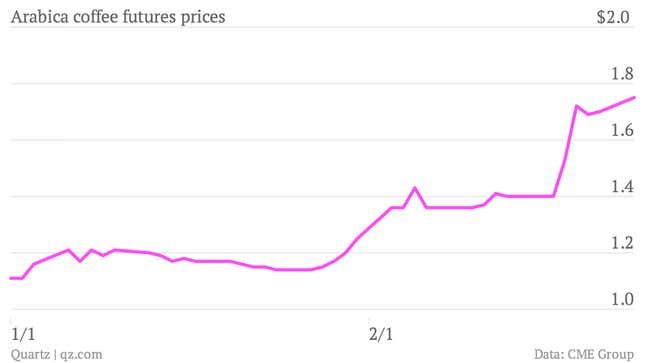

An extended drought in Brazil has significantly curbed expectations for this year’s coffee harvest. The crop could fall below 50 million bags, which would be about eight million short of the country’s production potential. While that’s good news if you’re invested in coffee futures, it’s terrible news if you’re buying the stuff wholesale. The anticipation of a shortfall has sent prices of arabica coffee—the kind Brazil produces, and which many higher-end coffee makers, including Starbucks, prefer to robusta—up nearly 60% since the beginning of the year.

While it hasn’t yet resulted in more expensive coffee at the counter, it could soon. But it also could lead to the start of a subtle bean migration that could negatively impact the taste of coffee blends.

Robusta beans, which are grown in Southeast Asia, and known for their bitterness (and use in instant coffee), have been getting more expensive, too. But their price increase has still been dwarfed by that of arabica, and that’s only further widening the price gap between the two. The price difference is now the highest it’s been since January 2013, according to Rabobank analysts. And it’s come despite an expectation that the price gap would actually shrink.

Robusta beans have long been recognized for their cheapness, but also their lower quality (in the eyes of higher-end coffee makers, anyway). The bigger that price gap gets, the better the chances robusta beans begin to make their way into more and more coffee blends. “[W]ith arabica prices spiking, more robusta may be incorporated into blends, lifting the demand outlook and supporting prices,” Rabobank explained in its note. Some savvy coffee drinkers in the past have complained about other price-related increases in the use of robusta in coffee blends.

As the world continues to down more coffee each year—consumption has grown by an average of 1.2% each year since the 1980s, according to the International Coffee Organization—the impact of poor coffee harvests will only prove more severe. At the moment, Brazil’s troubles could lead to less tasty coffee, at least temporarily, around the world. But down the road, production problems could lead to outright global coffee shortage. Coffee supplies are expected to outpace consumption by about 400,000 bags this coming year, according to Bloomberg, a far cry from the four million bag surplus achieved this past season.