Relations between Malaysia and China may be at an all-time low after the March 8 disappearance of a Malaysia Air flight carrying 154 Chinese passengers. But there’s one connection between the two countries that’s not likely to change: a small but quickly growing wave of Chinese nationals who are moving to Malaysia to escape pollution, food scares, and political constraints.

China’s wealthy elites, keen to emigrate or at least reserve the option to do so, have traditionally flocked to Canada, the US, Australia, the UK, or developed Asian cities like Singapore or Hong Kong. But as restrictions in some countries have tightened, Malaysia has become an alternative immigration destination for China’s wealthiest as well as its middle-class families.

“Malaysia My Second Home”

“The living cost here is not high,” Wang Dong told Quartz. Wang, 43, gave up a career in international logistics and moved his family from Shanghai to Kuala Lumpur last year. The couple was worried about growing pollution and food safety, and disenchanted with a school system that they believe overloads young children. The family now owns a home in the capital, Kuala Lumpur, and their daughter attends a local elementary school.

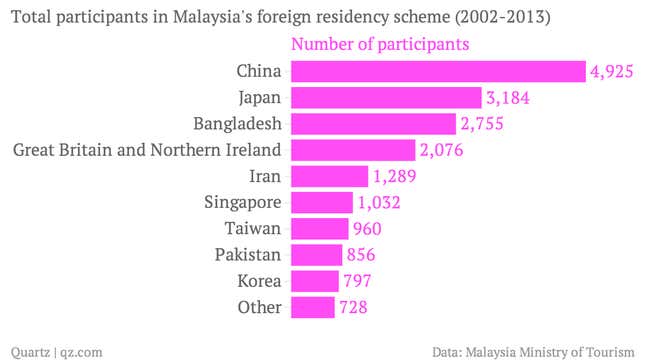

Wang is one of almost 5,000 Chinese who have the right to live indefinitely in Malaysia under a foreign residency scheme called “Malaysia My Second Home,” or MM2H. Started in 2002, the program targets wealthy foreigners who will hopefully buy property and cars, invest in the stock market, or open businesses.

The MM2H program is easier to get into than similar schemes in some other countries. Foreigners under 50 with liquid assets of at least 500,000 ringgit (about $152,800) are eligible; those older than 50 need only 350,000 ringgit. In contrast, foreigners hoping to participate in America’s investor immigration scheme have to sink at least $500,000 into the country and create 10 jobs for Americans.

Chinese families have tended to settle in Kuala Lumpur, drawn to its high-quality schools. Chinese telecom giant Huawei also has an operation in the capital and some of its employees have applied for MM2H visas, staff told Quartz. Penang, an island off the northwest coast known for its blue-sky days and white beaches, is similarly popular with Chinese retirees.

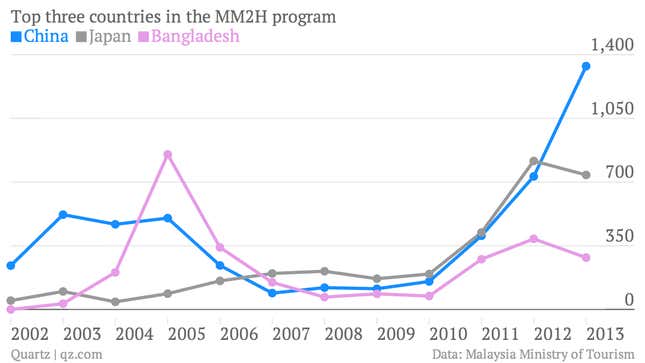

In all, there are more MM2H visa holders from mainland China than from anywhere else. Applications from China have spiked since 2012, while those from other countries have fallen:

They bring their money with them. Last year, Chinese institutional and retail investors poured $1.9 billion into Malaysian real estate, more than in Hong Kong, Singapore, or Australia. At least four mainland property developers announced plans to invest some $4.8 billion in the country this year—but that was all before Malaysia Airlines flight #370 went missing last month.

A bad year for friendship

Since the flight vanished, Chinese media and the public have been furious at Malaysia for what they believe have been bungled rescue efforts. Chinese travel agencies have seen a steep fall in interest in travel to the country. Officials have delayed delivering a pair of pandas (paywall) to Kuala Lumpur, a withdrawal of one of Beijing’s favorite gestures of friendship. The recent abduction of a Chinese tourist in Sabah, Malaysia has only made things worse. It’s been a terrible beginning to what was supposed to be the “China-Malaysia Friendship Year.”

But according to MM2H participants and promoters, the MM2H program has so far withstood the shocks. “Every day we have one or two clients signing contracts with us. It is the same as before,” says Nicole Xian, a marketing director of a Guangzhou-based MM2H agency. She describes the steady growth of applicants to the program as ”rigid demand,” based on families that have planned their decision far in advance. She believes that isn’t likely to change because of one accident.

Real estate operators in Iskandar, a development zone in southern Malaysia, say interest may be affected in the short-term but should bounce back soon. Iskandar is where some of China’s largest property developers, like Country Garden, have built serviced apartments, luxury sports clubs, shopping centers, and an amusement park. One Malaysian property developer told local media, “Business and investments decisions are based on calculated risks and not easily swayed by emotions. Last I checked, there are still busloads of prospective Chinese buyers coming to Iskandar.”

“People here are mild and compare less”

The continued appeal of Malaysia’s foreign residency program has a lot to do with conditions in China—what some migration experts call the “push” factors. Many young and middle-aged Chinese face increasing pressure to earn enough to buy a home, take care of their parents, and raise a family, all in the face of sky-high housing prices, a depressed savings rate, and an elderly population that’s growing faster than the number of young people who can care for them.

Malaysia provides some respite. Dong Cheng, 46, who holds a MM2H visa and has lived in Kuala Lumpur for more than half a year, says, “I feel that the people here are mild and compare less [i.e., are less competitive].” Travel, food, and health are the common topics of discussion among Chinese expatriates, Dong says; he often travels to Penang and Langkawi, a cluster of Malaysian islands in the Andaman Sea, for vacations.

Politics at home are another motivating factor. Government and public scrutiny of wealthy families has some households eager to move abroad. Others just worry about where the country is headed. Chen Tien-Shi, an associate professor at the School of International Liberal Studies at Waseda University in Japan, compared the recent MM2H trend to the exodus of Chinese from Hong Kong before the 1997 handover back to the mainland.

“The latest wave of emigration has been prompted, I imagine, by such factors as the domestic political situation and anxiety about environmental pollution and their own livelihoods,” he wrote in February, after visiting Iskandar. “The movement of Chinese nationals abroad always appears to be linked with domestic conditions.”

“Time will heal the wound”

The number of Chinese families moving to Malaysia also reflects a long history of friendly relations between the two countries. Malaysia was the first member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to establish diplomatic ties with China in 1974, when others wouldn’t, notes Richard Hu, an associate professor of international relations at Hong Kong University.

And even though Malaysia also claims territories in the disputed Spratly and Paracel Islands in the South China Sea, it has avoided public spats with Beijing. Today, China is Malaysia’s largest trading partner, and Malaysia is China’s top trading partner in ASEAN.

Cultural connections also run deep. Almost a quarter of the Malaysian population is ethnic Chinese who migrated there throughout the during the early-to-mid 20th century; Chen calls the recent crop of Chinese MM2H-ers Malaysia’s “latest wave of Chinese emigration.” In a region where sentiment against ethnic Chinese has been known to turn violent (pdf), such feelings appear largely dormant in Malaysia, where the bulk of Chinese are now third- or fourth-generation descendants of earlier migrants who often identify as Malaysian first.

Many of MM2H residents don’t have a clear plan for how long they will stay. The Malaysian government allows them to renew their 10-year visas indefinitely. “It is hard to predict the future,” says Wang. “We will stay in Malaysia in the upcoming years, at least until our daughter’s junior high school or high school graduation.”

He still believes that many more Chinese will opt for taking up residence in Malaysia: “The disappearance of MH370 may affect Chinese people’s enthusiasm for travel in Malaysia in the short term, but time will heal the wound.”