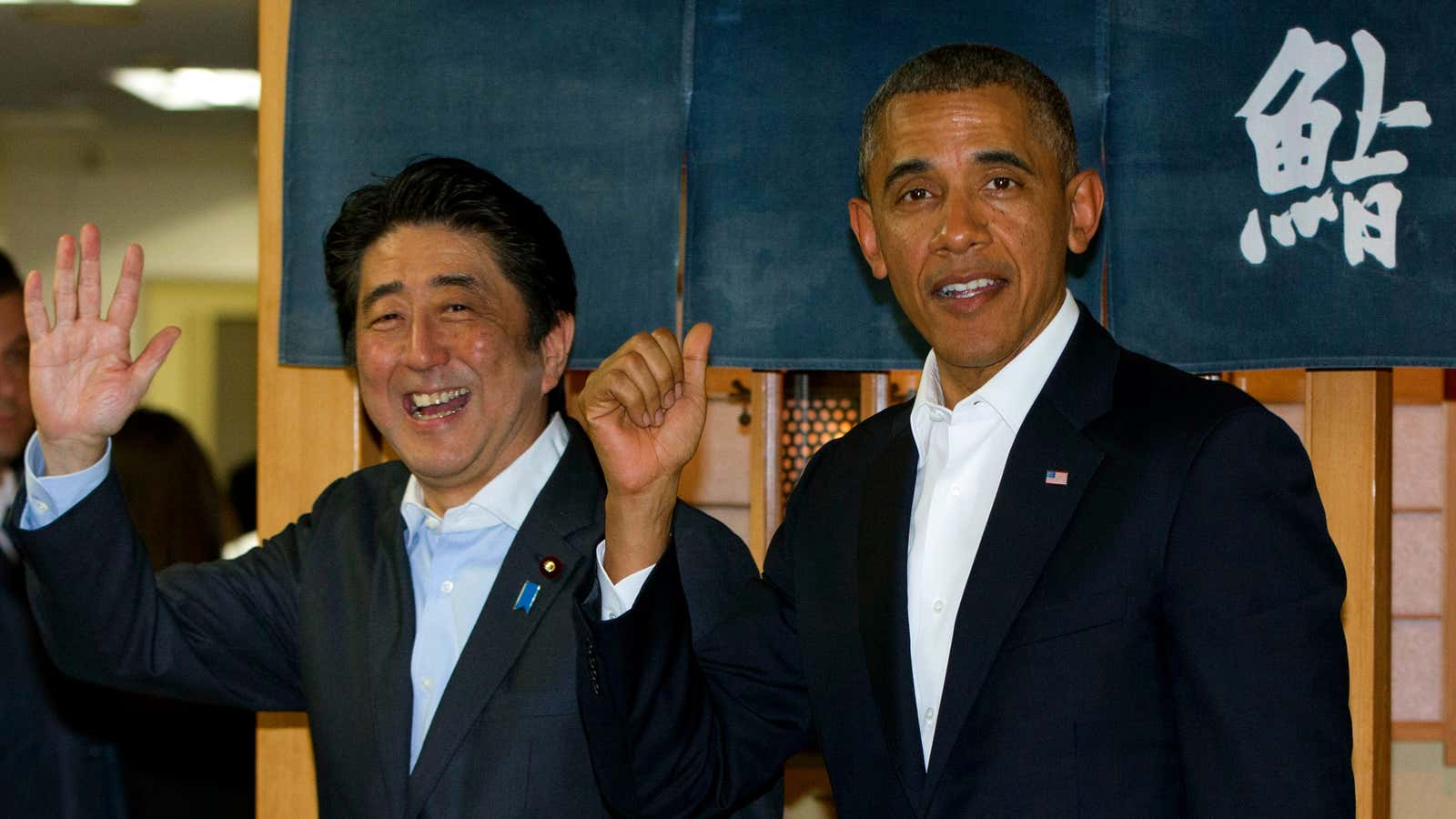

US president Obama and Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe sat down for dinner today at Sukiyabashi Jiro, the restaurant made famous by a documentary about the chef’s relentless pursuit of perfection. But if Obama, on a state visit to Japan, and Abe are seriously pursuing a trade pact that requires the political equivalent of Jiro’s deft knife-work and exquisite timing, they’re looking in the wrong place.

Officials are portraying the visit as a last shot to announce a final agreement between the two largest participants in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a multi-country free trade arrangement that includes countries across the Pacific rim. For Obama, the deal would solidify his administration’s “Pacific pivot” to counterbalance China, increase US trade and add another achievement to his legacy. For Abe, the deal represents the third arrow of “Abenomics,” his economic reform plan that aims to pair reforms like trade liberalization with fiscal and monetary stimulus to awaken his country’s stagnant economy.

Currently, Japanese negotiators are still pushing to keep tariffs on agricultural imports like rice and beef, one of the key obstacles to finalizing the deal. Obama hopes to pressure Abe toward concessions with his trip, but those concessions are far from likely because of Obama’s troubles with the trade pact back in Washington.

To pass a trade agreement, the president needs Congress to pass a special bill called trade promotion authority (TPA), which gives the president a negotiating mandate and a clear path to approve it. But TPA is not going to pass before November. Simply put: While the US business community is pumped about the talks, progressives in the Democratic party’s base are decidedly not.

The process by which trade deals are negotiated is extremely opaque, which upset members of Congress and left key interest groups, including environmentalists, labor unions and civil libertarians, feeling left out. Leaks of the negotiating texts confirmed their fears: The texts showed trade negotiators pushing for restrictions on intellectual property that contravene US law and allowing loopholes that might be exploited by cigarette companies fighting health laws.

Obama might be inclined to work around or over these objections, but this is an election year in the United States. The president and his allies know they need maximum enthusiasm in the fall, not a bitter intra-party debate. That’s especially true when the White House knows it can’t rely on Republicans, generally supportive of free trade, to carry a bill like this and provide a legislative victory.

After November’s election, a TPA bill is likely to be approved. But to do so might mean changes to woo progressives, including instructions about the deal that contravene what negotiators have already agreed on, particularly with regard to currency manipulation to promote exports, a move that Japan has been accused of adopting with its aggressive monetary stimulus. If you were Abe, would you give concessions on agriculture if you knew more would be asked later?

“If I were the Japanese, I wouldn’t close,” a former US trade negotiator who is following the talks told Quartz. “Why would I close and make all these sacrifices on agriculture, if I have a sneaky suspicion that you’re going to come back to me with a TPA bill that requires me to do more on currency than I want to do?”