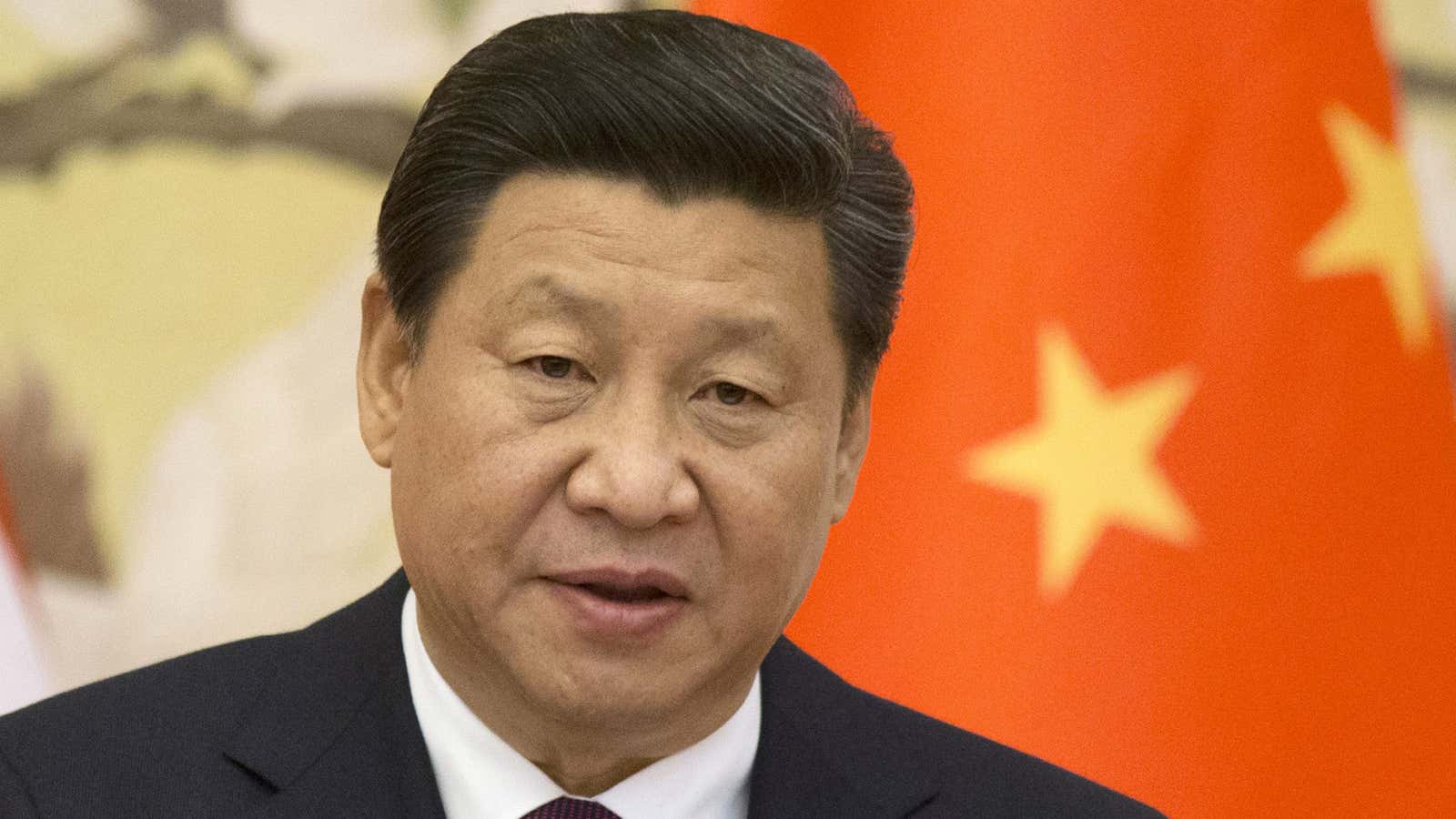

In 2013, China’s Communist Party, led by Xi Jinping, silenced human rights defenders and popular internet voices, while also setting new austerity rules for party members. This year, the crackdown became even more expansive, as Xi worked overtime to oust corrupt officials and jail moderate critics. But it also started to get decidedly weird, as China rolled out restrictive new cultural guidelines that often inspired outright mockery.

Below is just a partial list of what China banned in 2014:

More foreign media

A January 21 investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists uncovered links between family members of Communist Party elite and a far-reaching network of offshore tax havens. Any foreign media outlets that reported on the links, including the Guardian, Le Monde, El Pais, and the CBC, were immediately blocked inside China.

The government also stepped up its blockade of foreign websites for the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen Square massacre in June, and again after Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement protest that began in September. By the end of the year there were only a handful of foreign news websites operating in China.

Pornography (again)

Sexually explicit content has been illegal in China since the People’s Republic was founded in 1949, but that hasn’t prevented citizens from enthusiastically consuming it. Beijing’s latest “cleaning the web” initiative—which targeted websites, search portals, mobile app stores, and TV set-top boxes that provide access to porn—may have deeper political aims. The technology employed in porn bans has been used to censor political content in the past.

Windows 8

On May 20, government offices were banned from upgrading to the latest Microsoft Office operating system, leaving local IT teams little choice but to stay on unstable, easy-to-hack Windows XP, or a locally-created system with a shorter track record. Ubuntu Kylin, the “home-grown” operating system that the government is backing, has more than a few rough edges and was in fact largely created by foreigners.

Adultery (Communist Party members only)

Having at least one mistress is so common for powerful men in China that it is believed to be a factor in high property prices in Beijing, and many mistresses have become whistleblowers in corruption cases. Perhaps wary of the latter, CCDI, China’s top anti-corruption body, declared on June 7 that Party members would be henceforth held to a higher moral standard than the rest of the population, and committing adultery would be grounds for dismissal from a post, and banishment from the party.

Unapproved reporting

Journalists in China who published politically sensitive reports of internal corruption or cover-ups have risked arrest in the past. But new rules published June 18 forbid them from even reporting on a topic that doesn’t have previous approval, or reporting on topics outside their usual beat.

Ramadan

The Islamic religious festival started world-wide on June 28, but many Muslims in China did not participate. Fasting and other religious activities were banned at government offices, hospitals and schools in China’s Xinjiang region, where about half of the population is Muslim.

New government buildings

In late July, the party put a five-year moratorium on the construction of new state-owned buildings, perhaps to discourage continued construction of lavish, underutilized eyesores like the Harmony Clock Tower that have sprung up across the country.

Art without Socialist characteristics

“Socialist literature and art, essentially speaking, is the people’s literature and art,” Xi said during an October 15 speech. “Literature and art must reflect well the people’s wishes; it must persist in the fundamental orientation of serving the people and serving Socialism.” It must also not “stink of money,” he said, and should “save righteousness for history,” while “present[ing] beauty and virtue to the people of the world.” Xi also said during the same speech (in remarks that were reportedly deleted from the official account) that qiqiguaiguai, or “weird” cutting-edge buildings like the Rem Koolhaus-designed CCTV tower, should no longer be built.

“Lewd” content in film and television

On Nov. 13, China’s top media watchdog, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, issued a blanket ban on TV shows, films or online that show a huge range or human behavior. They include “polyamorous relationships, one-night stands, sexual abuse, pornographic content,” according to a state-run news site, as well as depictions of “rape, fornication, necrophilia, prostitution or masturbation,” plots containing “violent murder, suicides, kidnapping, drug abuse, gambling or supernatural occurrences” and websites that show pictures or contain text describing “sex and nudity.”

Enforcement of the ban could make it tricky for Internet giant Tencent to show any TV shows from its new partner, HBO, though it’s unclear how strict enforcement will be. The premiere of 3D gangster movie “Gone with the Bullets” was delayed for several days to satisfy censors, but, some netizens have noted happily, still contains a lap-dancing scene.

Puns and other word games

The late November ban on “the irregular and inaccurate use of the Chinese language, especially the misuse of idioms,” technically only applies to press, broadcast and advertisements, but it carries a chilling message to China’s netizens: the party is not amused by your clever use of wordplay to discuss verboten topics online.

Unapproved performances of the national anthem

The anthem, “March of the Volunteers,” reflects “national independence and liberation, a prosperous, strong country and the affluence of the people,” so should no longer be played at weddings, funerals, balls, entertainment events or in commercial arenas, according to state media, as it explained the new “standardized proper etiquette” introduced in mid-December.

Umbrellas (at least around Xi)

After umbrellas accidentally became the symbol of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests, press and bystanders were forbidden from using them during Xi’s rainy two-day trip to Macau. The press were handed raincoats instead, the AFP reported.

What’s in store for next year?

In 2014, Xi has managed to continue consolidating power within the party, while deftly disposing of potential rivals, and strengthening the party’s oversight of China’s 1.3 billion people.

But is tightening the vise on civil society and the party itself creating a more stable society and country, or one where people are simply more dissatisfied? It is hard to find many voices inside China willing or able to answer that question honestly, and those on the outside who are sounding the alarm are often the same voices who have been warning for years that Chinese citizens are on the verge of may revolt for years.

Zheping Huang contributed reporting.