Once in a while, a single accessory can define a fashion season, or begin a new era for a well-established brand. This fall, a pair of Gucci loafers, compliments of the label’s new creative director, Alessandro Michele, did both.

The shoes—embellished with Gucci’s signature metal horsebit, their interior bursting with a fluffy fur lining—spread across social media when they hit the runway at Gucci’s men’s show, reappeared on the catwalk a month later for women, and are now splashed across September fashion magazines and the shelves of Saks Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdale’s, and Nordstrom.

What’s interesting about these shoes is not just their appearance, but their materials. Those leather Gucci loafers—along with some women’s clogs and heels—are lined in wild kangaroo fur.

Some will find the idea of Australia’s adorable mascot ending up as an insole appalling, but a spokesperson for Kering, the luxury company that owns Gucci, says the fur is actually environmentally friendly:

“Kangaroo harvest is one of the best examples of a well-managed harvest program, and thus can be classified under our guidelines as a sustainable fur,” she told Quartz, confirming that the fur comes from wild Australian kangaroos.

Wild fur, as Quartz has reported, is relatively rare on fashion’s runways. Those who ethically oppose the killing of animals for human consumption will find no comfort in fur obtained from wild animals. But for others, the well-regulated hunting of a carefully managed wild population could be a more acceptable source of fur than farms—which are often criticized for mistreatment of animals and environmental damage—just as wild game makes a palatable alternative to factory-farmed meat.

Like deer in the US, kangaroos are often viewed as pests in Australia: Farmers complain that kangaroos destroy their crops and fences, conservationists are concerned they may threaten biodiversity (pdf), and and car collisions with kangaroos in Australia are commonplace. (One insurer counted more than 600 claims for kangaroo-related accidents in the Australian Capital Territory alone.)

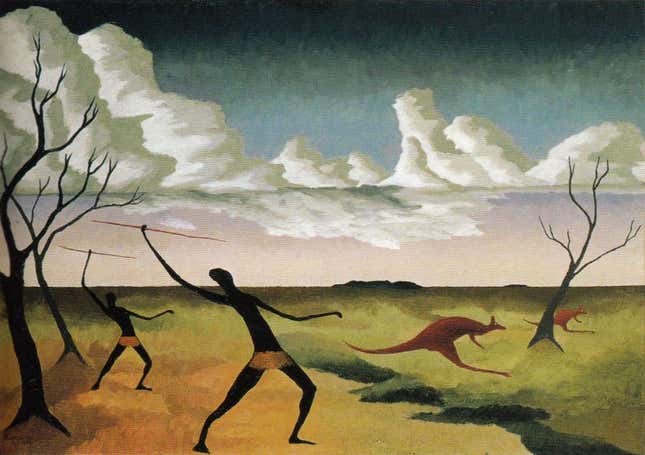

However controversial, kangaroo hunting has persisted in Australia for millennia. Aboriginal people hunted them for meat and tools, and for newly arrived British colonists in the late 1700s, the creatures were a source of novelty and then, sport hunting. (Captain James Cook spotted one on a short walk from his ship in 1770 and described an animal that was colored like a mouse, shaped like a greyhound, and hopping like a hare.)

When those colonists became farmers, they worried that kangaroos competed with their grazing sheep and cattle for food. That belief persists today, with farmers investing heavily to protect their land from kangaroos.

Some oppose any hunting of the marsupial. Daniel Ramp, the director of the Centre for Compassionate Conservation at the University of Technology, Sydney, says there’s no argument for hunting kangaroos that is ethically sound. “Kangaroos in particular are highly social creatures,” Ramp told Quartz. “They’re a wild animal, and they need to be left alone.”

Others focus on making sure that hunting is managed carefully. Steve McLeod, a senior research scientist specializing in kangaroos at New South Wales Department of Primary Industries, is not convinced by farmers’ worries about kangaroos competing for food with livestock; he says that sort of competition for resources is rare, though times of drought—and parts of Australia are experiencing a serious one—can be exceptions.

“My interest is not in the ethics of whether we should be using [kangaroos] or not,” says McLeod who, like Ramp, has participated in studies of kangaroo populations and hunting for around 20 years. “It’s to ensure that if they are going to be used, then they’re used in an appropriate way that’s sustainable and doesn’t impact on the viability of kangaroo populations.”

Australian state governments monitor commercial kangaroo hunting—also known as “culling” or “harvesting”—through a quota system, not unlike the ones in place for deer in the US. Those quotas vary from year to year, based on annual population surveys of the four species of kangaroos allowable for commercial export. This system, known as “proportional threshold harvesting,” usually sets the quota at between 15 and 20 percent of a species’ annual estimated population, but McLeod says commercial hunters rarely, if ever meet it.

How do they know? Each shooter, McLeod explained, applies to a management agency to purchase a set quantity of tamper-proof tags, and processors can’t accept a kangaroo without one.

And not just anyone can purchase the tags. Shooters must be trained to kill a kangaroo quickly, with a shot to the head. The specifics are not for the faint of heart (pdf), but they are in place to minimize suffering, and kangaroo shooters are known for their efficiency and precision.

That’s not to say unlicensed shooting of kangaroos doesn’t occur—but those animals can’t be sold. In that sense, commercial demand for kangaroos encourages hunters to comply with regulations. Right now, it’s mostly meat and leather driving that demand.

Paper-thin kangaroo leather showed up in recent menswear collections by Berluti and Loewe, and manufacturers of football cleats favor the material for its elasticity. Much like cow leather, kangaroo hides are generally a byproduct of the meat industry. In fact, in some states, “skin only” shooting is illegal. This efficiency of use—“nothing is wasted”—is an ethical justification some fur-averse consumers use for wearing leather.

It’s an argument that might be extended to fur from wild game, if manufacturers and brands are willing to make their supply chains even more transparent, and consumers are willing to consider that the ethics surrounding fur can go beyond simply “for” or “against.”

Those Gucci loafers looked interesting on the runway, to be sure. Whether consumers can feel good about what’s inside them is a more complicated question.