Talking about fur—the pelts of animals used for clothing such as coats, hats, and mittens—makes many understandably squeamish. There’s no denying the material’s origins: Fur was once the skin of a living creature.

So it stands to reason that some people cannot abide its use, just as some abstain from meat, milk, or any other animal by-products. Its detractors are passionate, and good at spreading photos, videos, and reports that highlight the material’s ugliest aspects.

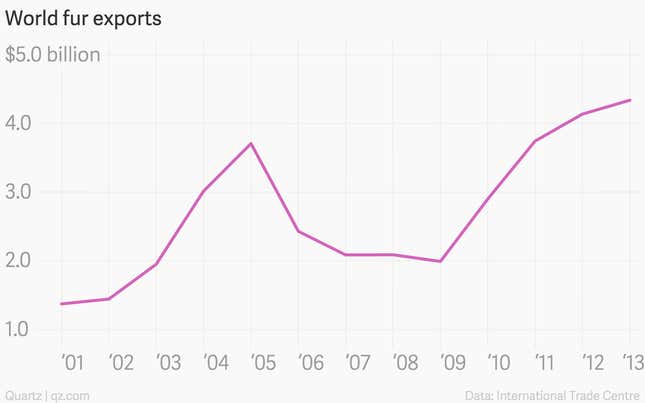

But however you feel about wearing fur, it doesn’t seem to be going away. Between 2008 and 2013, world fur exports more than doubled, from $2 billion to more than $4 billion, according to data from the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization.

At the fall/winter 2015 fashion shows (currently underway in Paris), fur has appeared in aquamarine overcoats, Chewbacca-style slippers, and packs of plush fox collars. Karl Lagerfeld recently announced a new fur-devoted show from Fendi. And the eastern US is still enduring another merciless winter.

It’s time to have a more nuanced conversation about the material, one that goes beyond simply FOR (or at least, “okay with”) or AGAINST, and acknowledges the ethical nuances involved. Yes, some aspects of the fur industry are absolutely horrific; living creatures suffer miserably for the greed of others. But the ugly truth is that this applies not only to fur, but to myriad other materials in the apparel industry—and sometimes those creatures suffering are human workers.

The question of whether fur can ever be ethically sound is one animal rights activists effectively silence, with a resounding “no.” But not all fur is created equally. Fur, like so many other natural materials, is not just black and white. Here, we attempt to distinguish some of the gray areas.

Wild fur

Just as some meat comes from wild animals—think venison or quail—so does some fur. Wild fur is less expensive than farmed fur, as the quality is difficult to control—a life (and death) in the wild can lead to scratches and irregularities in the animal’s coat. But some might prefer to wear the pelt of an animal whose days were spent frolicking in the woods over one that was raised in a cage.

The International Fur Trade Federation (pdf) says that around 15 percent of fur comes from animals such as beavers, raccoons, foxes, coyotes, and muskrats that are wild, as opposed to farmed. Fur labels often don’t specify if a piece is made from wild fur, but if you’re after a free-range fur, your best bet is to look for skins of animals such as beaver, coyote, muskrat, and raccoon from Canada, the USA, and Russia, where most wild pelts come from.

Many North Americans are already supporting the wild fur trade: It’s wild coyote fur that lines the hoods of those Canada Goose parkas currently stampeding New York City’s sidewalks. (See 1:20 in this video from the company.)

Invasive fur

Just as eating invasive fish has become a priority among environmentalists in the food world, using the fur of invasive animals could be a good way to make use of animals killed to protect fragile ecosystems.

For a species to be considered invasive, it must be harmful to the environment and be non-native. In the coastal United States, the nutria—a large, semi-aquatic rodent with webbed feet, long tails, and carrot-colored teeth—is both.

Since the 1930s nutrias, originally from South America, have been gobbling up the wetlands of coastal Louisiana, contributing to land loss that approaches 25 square miles per year, along with billions of dollars. The rodents, originally imported by fur farmers (as explained entertainingly in this New York Times video), chomp on marsh plants at their bases, which kills their roots. An area approximately the size of Delaware has already disappeared into the Gulf of Mexico.

In the 1990s, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries created an incentive program: they would pay registered hunters and trappers four dollars for each nutria they killed. (The price has since been raised to five dollars.)

“I didn’t get into invasive species management to kill animals,” says Michael Massimi, the invasive species coordinator for the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program, a conservation coalition administered by the Environmental Protective Agency. “I’m an animal rights advocate. But the damage they’re doing is existential.”

Massimi says wetland damage has declined every year since the program was implemented in 2002, but that 90 percent of the nutria carcasses harvested—last season there were about 400,000—are discarded.

Nutria fur, which, according to the Fairchild Dictionary of Fashion, has “a velvety appearance after long guard hairs have been plucked, with colors ranging from cinnamon brown to brown with gray stripes,” was once worn by Greta Garbo and Elizabeth Taylor, and had another moment in the fashion spotlight in 2010, when it appeared in collections by designers such as Oscar de la Renta and Billy Reid. But of course fashion is fickle, and demand has since slowed.

With a fashion project called Righteous Fur, Cree McCree, a New Orleans-based writer and artist, is seeking to drum up the market again. “It seemed to be this really criminal waste,” says McCree. “These nutrias were being killed for the coastal wetland control program, and then just throwing them in the swamp.”

At her periodic fashion shows, McCree sells items such as stoles, coats, messenger bags, and iPad cases. She also works with a local processor to prepare pelts for wholesale trade.

The New Orleans-based designer Kate McNee sells nutria headbands and slap bracelet-style cuffs made from McCree’s Righteous Fur, but for now, McCree takes less than 10 percent of the incentive program’s nutria carcasses. Until more mainstream designers take up the mantle, invasive fur is still a sideline business.

Roadkill fur

When the sustainability consultant Pamela Paquin returned to her native New England after several years working in Europe, she found herself overwhelmed by the animal carnage she saw on roads and highways.

She looked at the data about roadkill in the USA—estimates range from several to hundreds of millions of animals killed by cars each year—and resolved to begin her company, Petite Mort Fur. She now sells hand-muffs, scarves, hats, mittens, and leg-warmers made from the collateral damage of American car culture.

“Here is a resource that’s going to be there, whether or not we use them,” she says. “We can turn our noses up at them, drive by, treat them with disgust, disdain or we can stop and treat them with respect, and use what’s there.”

Paquin’s company is still small—she skins the animals, makes everything herself, and likes to connect personally with each customer—but her ambition is huge. She wants to revolutionize the fur trade by making roadkill (which she calls “accidental fur”) a viable sector of the market.

Personally, Paquin tells Quartz, the process of skinning the animals is a labor of love: “It’s so intense,” she says. “Quite often they’re partially frozen, so it can be a slow process. They’re beautiful. They’re beautiful. You can see their bodies and imagine their lives.”

She’s developing an app to help the Department of Transportation and wildlife officers track dates, species, and GPS coordinates of roadkill. The app would not only help her find the pelts for her business, says Paquin; it also would indicate problem areas for collisions, where land bridges or barriers could help protect animals.

It’s easy to imagine a scenario in which progressive designers uncomfortable with the idea of killing animals for fur may work with a material like Petite Mort’s. Already, Paquin is selling fur-pompom-topped beanies that are knitted by a local alpaca farmer, and priced to compete with similar models from Moncler and Gorsuch.

Vintage or repurposed fur

With a vintage or second-hand fur, customers avoid directly supporting fur’s modern-day supply chain, and the brands that engage with it. Because fur has had so many fashionable heydays—the prim 50s, shaggy 60s, and over-sized 80s for starters—vintage stores are overflowing with the stuff, as are many grandmothers’ closets.

For those who have inherited a fur that feels too old-fashioned to wear, but too precious and warm to get rid of, there are options. If the quality is still good—ie: the coat feels supple and not dry or papery, and it’s not shedding hairs—there are lots of ways to repurpose the coat. A professional furrier can cut a massive mink coat into a slimmer shape, a cropped jacket, or even a vest and some mittens, earmuffs, or a hat.

If the thought of wearing fur on the outside just doesn’t appeal, you could even line a non-fur jacket with it. Vogue’s Alessandra Codinha tracked down the Vienna-based fashion label, Envie Heartwork, which lines parkas made from used military tents with recycled fur coats.

And if you’ve inherited a fur that you just can’t wear, the US secondhand clothing chain Buffalo Exchange accepts donations of real fur in any condition for animal rehabilation centers which use the material as comforting bedding for injured and orphaned animals.