Oil has wrong-footed our leading experts—again.

At the beginning of 2014, the world was marveling in surprise as the US returned as a petroleum superpower, a role it had relinquished in the early 1970s. It was pumping so much oil and gas that experts foresaw a new American industrial renaissance, with trillions of dollars in investment and millions of new jobs.

Two years later, faces are aghast as the same oil has instead unleashed world-class havoc: Just a month into the new year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is down 5.5%. Japan’s Nikkei has dropped 8%, and the Stoxx Europe 600 is 6.4% lower. The blood on the floor even includes fuel-dependent industries that logic suggests should be prospering, such as airlines.

China’s slowing growth is one big reason. Another, according to analysts, is the direct or indirect fault of oil prices, which are still down 5% this year despite a week-long bullish run, and about 70% since their June 2014 peak, with much uncertainty how much they will rise from here in 2016.

The misread of the market again illustrates oil’s unfathomability—despite being studied microscopically for 140 years by some of the highest-paid quants and analysts on Earth, oil confounds with maddening regularity.

But it also reflects the tendency of analysts to eagerly embrace a new financial trend first, and only later examine what could happen should it proceed to its natural extremes before suffering the seemingly inevitable hit.

Always in such situations, a few traders bet the other way, leading observers to declare them oracles. John Armitage, whose hedge fund made $1.5 billion last year betting on an oil bloodbath, hasn’t yet been crowned a sooth-sayer, though he could be at any time. On the other side, there are traders like Andrew John Hall, a long-time oil prophet who made a big bet starting in 2014 that oil prices were going back up, but they instead plunged; in 2015, he stayed with the bet, and by the end of the year, his hedge fund had reportedly lost more than a quarter of its value.

The analysts defend themselves by noting that they got this and that aspect of oil’s trajectory right, which is fair enough. But it seems all missed the big picture: First, they failed to see that from 2011 to 2014, a surge in shale oil production was going to become a big factor in global supplies; then, they did not anticipate that the same oil would create the mayhem before us now. In fact, in the case of the current turmoil, most forecast the precise opposite—economic nirvana. Interviews with the main institutions that made the bad calls reveal no crisis of confidence, and they are busy putting out analyses of the latest developments.

We live in a time of bad forecasting of all types. Examples include the failed predictions of political pollsters gauging a host of critical elections around the globe, and the delusionary thinking that led to the last American economic catastrophe wreaked on the world—the 2008 mortgage crisis. It’s hard to predict events, as Philip Tetlock described last year (paywall) in his book Superforecasting.

Even so, the sheer scale of what was not foreseen in oil (mea culpa: including by Quartz) is breathtaking.

Consumers have been big winners—gasoline prices have plummeted. That part has happened. But analysts failed to anticipate that the Saudis would refuse to cooperate with the shale gale, as it’s been dubbed, and in fact would declare war on it, even though Riyadh did precisely the same thing in the 1980s. The analysts did not foretell that, if shale oil production rose as they projected, it could drive down prices not only to the $80-a-barrel average that many forecast, but much lower—so low, for so long (see chart below), that companies would put on hold $380 billion (and counting) in oil and natural gas field investment, and fire 250,000 industry workers around the world last year (including around 90,000 in the US).

Nor did they foresee that many of the companies themselves would be at risk of bankruptcy (42 already filed as of last year). Of 155 US oil and gas companies studied by Standard & Poor’s, one third are rated B- or less, meaning they are a high risk of default. These companies’ debt is selling at just 56 cents on the dollar, below even the level during the financial crash. As a measure of this vulnerability, the 60 leading US independent oil and gas companies have accumulated $200 billion in debt.

In the bigger picture, none took account of the emerging markets’ addiction to investment from OPEC, whose billions of dollars today are either being withdrawn or simply no longer sent. This, along with an evaporation of recycled petrodollars from Europe, is consigning those emerging nations to recession, as reported first by Izabella Kaminska and her Financial Times colleagues.

“Unfortunately, we are all slaves to history,” said Robin Mann, an energy analyst with Deloitte. “We kind of fall back to what historically has happened.”

What is that history?

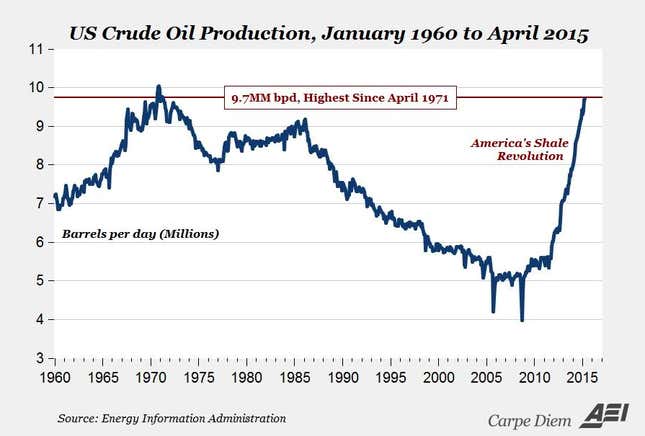

Since the 1970s, OPEC, the Saudi-led oil cartel, has governed oil prices by artificially restricting production in its members’ oilfields; there was never a global shortage, but OPEC’s market behavior created the illusion of one. Petroleum production in the US—once the world’s largest supplier—peaked in 1971 (see chart below), and it went on a slow decline, resulting in higher and higher imports, and an evolving shortage of natural gas, too. By 2008, the industry mantra was that cheap oil and gas were history; the only question was how high oil prices could go.

As an illustration of OPEC’s power, in the mid-1980s, Saudi Arabia became fed up with losing market share—its production dropped to as low as 3 million barrels a day (compared with 10.5 million today). So it flooded the market with oil, driving down the price to as low as $13 a barrel. In the process, a number of rivals were crushed, most harshly the Soviet Union, which collapsed entirely. But the Saudis recovered their market share.

By the early 2000s, oil demand from China, India, and elsewhere began to exceed supply—conditions for the so-called “superspike,” the famous rise of commodity prices—and oil’s long climb over $100 a barrel began.

Then, unpredicted and seemingly overnight, starting in the late 2000s, the US went from natural gas shortage to an enormous, 100-year overhang of the fuel. And there was a surge in US oil production that reached 4.4 million barrels a day by 2015. At once, the US was challenging the 1971 oil production peak.

The trigger was a boom in hydraulic fracturing—fracking—a drilling method that had opened up American shale fields, previously regarded as uneconomic. The catalyst for all of it was technology that lowered the cost of extraction, but also the incentive of high prices—US oil prices briefly went over $113 a barrel in April 2011, and stayed high.

With that rise in production came a Hallelujah Chorus.

Daniel Yergin, the oil industry champion and author of the 1990 Pulitzer-winning history The Prize, coined the expression “shale gale” to describe the impact he and his firm, IHS, forecast from fracking.

The US, Yergin said, was poised for an “industrial renaissance.” In an October 2012 report, IHS catalogued $5.1 trillion in spending from shale oil and gas production by 2035. In a December 2012 sequel, the firm went state by US state and detailed how, by 2015, fracking would employ some 500,000 workers. By 2020, the employment number would rise to 600,000 workers, and jobs supported by fracking would grow to 3 million, IHS said.

That was on top of the lower gasoline prices that would benefit all American consumers.

“This is probably the best economic news the US has had since 2008,” Yergin said.

One of the specific industries to gain from the boom would be steel, forecast Deloitte, the consulting firm, in a 2014 report. Given the expected demand from the oil industry as it built out its infrastructure, American steel companies could now compete head to head with rivals including China, despite the latter’s lower labor costs.

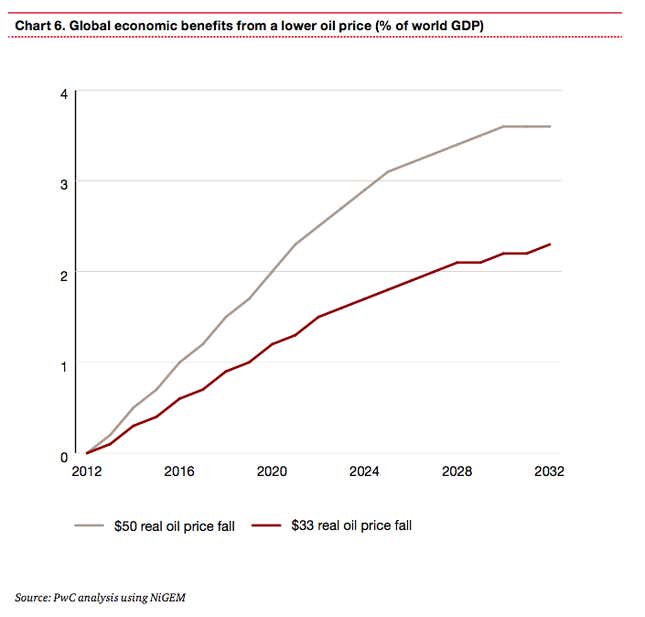

Adding to the growing glee, another major consulting firm, PwC, said that not only would shale be a big bonanza for the US, but it would drive a full percentage point increase in global GDP by 2016, and an extra 2.3% to 3.7% by 2032 (see chart below). In February 2013 (pdf), the firm did warn drillers that they should prepare for lower oil prices. But how low? If fracking spread around the world and began to produce 14 million barrels of oil a day—PwC’s estimate of the potential by 2035—oil prices would drop as low as $83 a barrel, the firm said.

Such studies, often paid for by the industry, accompanied forceful oil company lobbying to open more federal land to shale drilling, to forestall federal regulation of fracking, and to lift a ban on oil exports. The first two of those efforts—to open up more land, and to stop federal regulation—failed. But oil exports were eventually legalized.

On the shale patch itself, the politics were decidedly pro-fracking. When the Texas city of Denton voted to bar fracking within municipal limits, the industry came down hard, with the help of state politicians: the Texas legislature overturned the move by barring towns from regulating oil and gas drilling. Signing the bill, governor Greg Abbott said he was acting in the interest of “protecting private property rights.”

That’s when Saudi Arabia became unhappy

In summer 2014, Citigroup’s Edward Morse noticed that Saudi Arabia was offering its oil at lower prices than usual. Others reported the same, and it was inferred that, as OPEC’s leader, Saudi Arabia was suddenly out to push down the global price. And that is where it went—inexorably down. It was not clear how low it could go, although Morse had been forecasting for some time that it would average in the range of $65 to $80 a barrel by the end of the decade; now the plunge he foresaw seemed to be coming much, much sooner.

In effect, the Saudis had declared war on US shale. Then, in November 2014, the situation bode worse for the US-produced oil: The Saudis, meeting with fellow OPEC cartel members in Vienna, declared that US and other non-OPEC oil had to be driven out of the marketplace—the cartel as a whole had to go on a war footing. So it was that, led by the Saudis, OPEC, along with Russia, flooded the market with oil, leading prices to as low as $27 a barrel in January, a 77% drop from their peak in June 2014.

As Quartz has noted before, Morse has amassed a formidable record for getting big things right: Against the consensus, he forecast both of the most recent oil price plunges (in 2008 and in 2014). In both cases, he was subject to doubt often bordering on ridicule by his peers. There is no major oil analyst more oracular than Morse.

This time, though, while getting the plunge in prices right, Morse was less far-sighted about the rest. Like others, he forecast a US economic renaissance. Morse also missed Saudi Arabia’s war on shale. On not foreseeing the global economic mayhem, he told Quartz, “nobody got that right.”

Deloitte, too, got its steel forecast wrong: Instead of a bonanza for US steel, there was a plunge in demand, as the drop in oil prices prompted oil companies to cancel their projects. Chinese imports, meanwhile, continued to undercut the now-struggling American steelmakers. On Jan. 26, US Steel reported that it lost $1 billion in the fourth quarter of 2015.

This left analysts asking what went wrong

With the collapse in oil prices came the crash of employment in US cities across Louisiana, North Dakota, and Texas, and in Canadian towns reliant on the oil sands boom in Alberta. North Dakota has lost an estimated 13,500 roughnecks and oil engineers, not to mention drivers, restaurant cooks, barbers, and grocery store cashiers in service businesses that sprouted up around them. The Canadian province of Alberta has lost some 20,000 jobs, the most in any industry downturn since the early 1980s.

A lot of Americans bought houses based on confidence in the boom, and now can’t make their payments—Texas has seen a 15% rise in foreclosures, and Oklahoma a whopping 36% increase, according to estimates from RealtyTrac. Morningstar, the rating agency, has put a third of some $340 million in mortgage-backed securities tied to North Dakota apartment buildings and other commercial properties on its watch list for possible default.

But the echo has also been heard far from the US shale patch. In the once-booming, toughly run petro-state of Azerbaijan, for instance, people have been in the streets to protest higher prices and lost jobs; the International Monetary Fund, worried about Azerbaijan’s possible collapse, is speaking with government officials about a $3 billion bailout. Soup kitchens are surfacing in Moscow, notwithstanding Russian president Vladimir Putin’s assertions that the country is coping fine, and that things will improve this year. African producers also have felt the pain. Like stock bourses around the world, Nigeria’s has tanked along with oil prices.

Reid Morrison, an executive with PwC’s energy practice, acknowledged that the firm erred in its forecasts. He said that PwC, like a lot of analysts, thought that OPEC was already producing at its maximum output, so that shale would satisfy whatever demand developed on top of that. The firm also thought that, when any surplus developed, OPEC would cut production.

But he said that PwC fast caught on to what was happening once the facts changed. The firm went to clients with the changed circumstances. At a time when oil was selling for $95 a barrel, PwC now forecast the possibility of $50-a-barrel oil. But it was simply not believed. “The reaction we got from everyone was dismissive,” Morrison said. “They would say, ‘$80 a barrel is the new floor, so why are you being overly dramatic by talking bout $50?’”

Yergin did not respond to an email seeking comment. An IHS spokesman declined to comment.

Not all the analysts missed the clues. In 2012, with oil north of $100 a barrel, where the consensus said the price had to be in order to incentivize sufficient production to feed demand, oil economist Michael Lynch told an OPEC conference that the sustainable price of petroleum was $50 to $60 a barrel. He was more or less laughed out of the room.

Around the same time, Philip Verleger, an oil economist who runs a consulting firm out of Colorado, predicted Saudi’s war—in a May 2012 note to clients, he forecast a “Lehman event,” referring to the pivotal role of the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers in the financial crash.

Verleger is a ribald iconoclast with an encyclopedic knowledge of industry history, and a penchant for deriding the judgment of seemingly everyone else analyzing the market. In the Lehman note, he predicted that Saudi Arabia would do as it did in 1985—flood the market—and he timed it for later in 2012. Prices would plunge, he said. Even though the bull run went another two years, Verleger arguably still had more clarity than his peers.

What comes next?

In February 2015, Saudi energy minister Ali Naimi pondered aloud whether petro-states might suffer a black swan event, with oil demand drying up entirely by 2050. And then what would the Saudis do? It seemed like an off-the-cuff philosophical contemplation.

But Verleger suggests that it wasn’t—that the larger message of the current bedlam is that we are watching the autumn of the oil industry.

“Producing countries understand that oil not produced today may never be produced,” Verleger told Quartz. “Saudi Arabia was the first nation to come to this understanding. In response, they and other countries have acted to make sure their low-cost oil is produced first while the high-cost oil in nations such as Venezuela and Canada are left permanently in the ground.”

The notion sounds slightly wacky—does Saudi Arabia seriously believe the oil age is coming to an end? Saudi Aramco chairman Khalid al-Falih did say recently that the country intends to maintain its strategy, and keep producing oil at maximum production.

As for oil analysts, they are at odds over what that will mean for prices.