On the last Tuesday before the Chinese New Year holiday (Feb. 8-10) in the darkness of a cinema hall in Hong Kong’s Kowloon Bay, an audience of largely young people watched the dark, dystopic film Ten Years, while the hall filled with muffled sobs and wet sniffles. It was the sound of a restive new generation in Hong Kong watching their private diaries voiced out loud, and a prelude to that generation picking up bricks.

Released late last year, the film was a surprise hit. It took in over HK$6 million (about US$772,000) at the box office, making it one of the highest-grossing independent films in Hong Kong cinema history. It was a profitable one, too, having been produced on a budget of about HK$500,000. The film even beat the new Star Wars movie for several weeks, despite playing on fewer screens, yet Ten Years strangely vanished from theaters before its popularity had properly run its course.

It also earned a best picture nomination for the upcoming Hong Kong Film Awards. That, in turn, earned the displeasure of Beijing, with the Communist Party mouthpiece Global Times describing the film as absurd and pessimistic. QQ.com, a mainland China web portal, abruptly decided against showing the upcoming April 3 awards ceremony, as it had originally planned.

Much has happened in the three months since the film’s release.

- Hong Kong’s five vanished booksellers have yet to return from China.

- Riots broke out in the Mong Kok neighborhood, railing against Beijing’s influence and leaving over 80 injured.

- Student union leaders declared that they advocate an independent Hong Kong.

- Joshua Wong, one of the young student leaders of the 2014 Umbrella Movement protests, announced he will form a political party (paywall) to demand a referendum on Hong Kong’s future.

- Housewife Kwan Ying-yi unleashed a barrage of open frustration at the government during a Legislative Council meeting; within two days a subsequent YouTube clip received 300,000 views.

- The “localist” group Hong Kong Indigenous—with its candidate Edward Leung Tin-kei—won 15% of the votes in a New Territories by-election, signaling a possible strong showing in September’s general election for the legislature.

- Tens of thousands of social media users hurled Facebook’s new “anger” emoticon at Hong Kong’s chief executive, CY Leung.

- A “localist” politician and his family were reportedly contacted by Mandarin-speaking goons, who threatened to make him “disappear.”

Is Hong Kong at the breaking point?

People have little choice left but to throw bricks, believes Joseph Lian Yizheng, a respected local commentator, professor, and former policy maker. In a recent column in EJInsight.com, he wrote: “Sticking to non-violence can be the safest bet but when you are faced with an unyielding wall, one is ready to accept stronger tactics. As the dovish way has turned out to be a dead end, future protests can only take a more valiant form. Hong Kong’s democratic path is like an egg that breaks against a high wall. But after Mong Kok, the egg has now become a brick.”

Ten Years, a collection of five shorts, foreshadowed much of Hong Kong’s turmoil in recent months, including the targeted booksellers and the street protests—though the film ratchets up popular protest to include a self-immolation in the style of Tibetan monks.

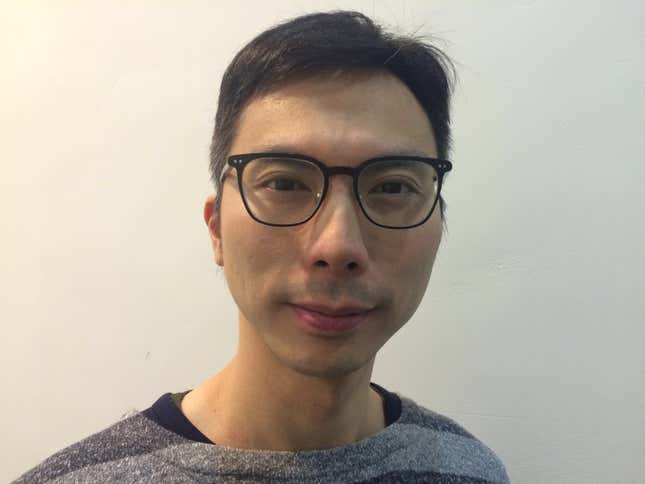

The film was conceived in 2013 by director Ng Ka-leung, 35, who had the idea while looking at a Chinese character for yu, meaning “threshold.”

“This situation can be Hong Kong’s situation,” he told Quartz following a Feb. 19 private screening of the film at Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HKPU). “We don’t know our direction, we don’t know if the change will be good or bad. There are many problems. We don’t know what to do. The character yu gave me a way forward.”

“I asked a lot of people about their history. ‘How do you see your future?’ And when they replied, they all had fire in their eyes,” continued Ng, who directed “Local Egg,” one of the film’s shorts. “They have time to make a change. There are many possibilities. That imagination gives them strength. I wanted to capture this feeling, to give them strength.”

The action of the film takes place in the near future and paints a grim picture of life for ordinary Hong Kongers under Beijing’s increasingly restrictive grip: booksellers driven underground; Hong Kong businesses and the Cantonese language strangled in favor of mainland concerns and Mandarin; dastardly political double-crossing by Beijing agents; Hong Kong children indoctrinated to turn on their parents.

Director Chow Kwun-wai, 37, who created the film’s “Self-Immolator” short, says this locally born, locally raised generation is unwilling to wait for China to hand them independence and democracy.

“Our relationship with the mainland is not the same [as the previous generations’]. Many people in this generation think we should have independence.”

A failure of government

The two directors—both sons of truck drivers—agree that earlier generations felt independence was impossible, that politics left them cold. Their elders hardly cared if Britain or China were in charge, as long as they could make a decent living. But this feeling has now changed, Chow believes, and Hong Kong needs a government that will be on their side, particularly in a punishing economy.

“Our government refers to China to solve problems,” he said. “They try to satisfy Beijing. They are not answering the Hong Kong people.”

Instead of addressing the youths’ problems and connecting with the people, Hong Kong’s current government has spent most of its energy colluding with Beijing, currying favor with the Communist Party, and lining its own nest, believe many young people in Hong Kong.

Frank Chen, a writer and translator at EJInsight.com, says Chinese president Xi Jinping has only one requirement of Leung, his handpicked Hong Kong lieutenant: allegiance. “Leung has failed to improve Hong Kong’s economic situation, but he is loyal,” Chen adds. “That’s his only talent—political struggle and infighting.”

Bitter infighting among opposing factions in the Chinese Communist Party plays out in Hong Kong, says Chen. This is reflected in the shifting approaches taken by the Liaison Office—China’s representative organ in Hong Kong—which is directly influenced by the top leaders in Beijing. Others have noted that Hong Kong’s booksellers’ kerfuffle is also a result of the party airing its dirty laundry.

Chen says the party’s internally warring factions will be working behind the scenes to influence next year’s elections for the chief executive, taking advantage of a complicated electoral college system. A 2010 study of the serpentine system concludes that the 1,200-strong election committee is “neither a microcosm of Hong Kong society, nor representative of the views of the general electorate,” and is in fact designed to protect Beijing’s interests.

A tangled history

The roots of Hong Kong’s fresh malaise reach back to the mid-19th century’s Opium War, when the flagging Qing emperor Daoguang was forced to lease Hong Kong Island to Britain in perpetuity, among other concessions. Further conflicts expanded the concessions to Kowloon and then the New Territories, which in 1898 was leased to Britain for 99 years.

The question of returning Hong Kong to China had boiled over well before the Communists came to power in 1949, though novelist Han Suyin only coined the ringing phrase “A borrowed place on borrowed time” a decade later. (See Philip Snow’s fine book The Fall of Hong Kong.)

There is no way that the island could survive without the attached, leased hinterland, which is why Britain was forced to return all of Hong Kong to China, under the terms of the Anglo-Chinese Joint Declaration of 1984.

London and Beijing hammered out the Basic Law, a mini-constitution to govern Hong Kong after 1997 that outlines a “one country, two systems” framework, designed to give Hong Kong significant autonomy.

But the promise of “two systems” is wavering, many believe. Squabbles between China’s hawkish and moderate factions lead to Beijing interpreting Hong Kong’s constitution differently, a 25-year-old post-graduate law student who recently watched Ten Years told Quartz.

“Different Chinese officials give different interpretations of the Basic Law, and now it’s more tilted to one country, [not two systems],” said the law student, who asked to remain anonymous.

As China wades increasingly into Hong Kong’s affairs with impunity and the local government turns a deaf ear, there seems to be little recourse for ordinary Hong Kongers who want a say in their future.

Student movements

Some 500 students attended the screening of Ten Years at HKPU, and many participated in a vigorous question-and-answer session afterwards. “Certainly two systems [means] two points of view. One [system] wants to be a democracy,” Dunchooprapha Thanawat, a leader of HKPU’s student union, told Quartz. “Hong Kong should be independent.”

In his EJInsight column, Yizheng cited Friedrich Engels. The German philosopher said in his later years that the only way to avoid violence was to hold free elections at all levels of a political group or a country, a means through votes and parliamentary democracy.

The law student, who had rushed to watch Ten Years, said the film’s message was explicit and welcome. “I really appreciated the film,” she said. “My generation is very active in discussing the future of Hong Kong. Even though it’s called Ten Years some of [the incidents] are actually happening right now. It’s difficult to find a job in Hong Kong without Mandarin,” just as the short “Dialect” predicts.

“My major concern is that Hong Kong will become more like China,” she continued. “Freedom of speech will be eroded, the judicial system [has been] compromised in the past—see how Judge Bokhary retired earlier than he was supposed to. He was always more liberal, and obviously against what the Chinese government wants.”

The student stressed the loss of a local identity—also the focus of Ng’s short, “Local Egg.”

“The Chinese government is using different methods to make us accustomed to Mandarin, and language is intimately related to our sense of local identity. It’s a very subtle process,” she said, and added that many of her friends had progressed from talking about leaving Hong Kong to actually looking up requirements to immigrate elsewhere.

“Most importantly, we don’t want to live in another Shanghai and Shenzhen, the culture is different between Hong Kong and mainland… Besides, the government really doesn’t care if you stay.”

Hope or despair?

In “Local Egg,” says Ng, a chicken farm symbolizes every kind of local industry—industries that are being sidelined in favor of mainland businesses, as part of the government’s hidden agenda. “Those have been Hong Kong’s actual values of the past years,” Ng said. “We reject that.”

Still, Ten Years holds an optimistic message, he notes. At the end of his short (spoiler alert), a Hong Kong boy participating in a Cultural Revolution-style youth guard is sent to attack his own father’s grocery store but refrains from destroying his merchandise.

“That is the hope in the darkness—maybe [people] can have a choice, maybe they can make room for change, the hope is that we make the choice. Although the background is not easy, people can make choices. One way to freedom is despair—they are two sides of a coin.”

Many viewers have asked the directors whether they fear saying such things could result in not being able to make movies in the future, Ng noted.

“Our film is honest,” he said. “We express ourselves [openly], and this is something seldom seen in Hong Kong. Such comments and this viewpoint should be a common thing [since so many people feel this way]. That is [the sign of] a healthy society. But at this moment of Hong Kong’s history, nobody is saying anything… our society is sick.”

“Hong Kong people are like orphans,” says writer Michael Somers, who witnessed the 1997 handover and is calling his upcoming Hong Kong novel Orphan City.

His book’s title plays on Hong Kong people being “children without parents who love them—the place is wanted only for what it can give, and that’s money,” Somers told Quartz. “Beijing expressly demanded of London that Hong Kong people be excluded from the Sino-British talks on Hong Kong’s future; Hong Kong people should have no voice, it said, and [the British] said, ‘Oh, okay.’”

The thing about orphans, though, is that they tend to be tough, and orphan cities in desperate times will certainly throw up some heroes. After the HKPU screening, one student asked the Ten Years directors, “Do you predict that the level of demonstrations will be more and more fierce?”

It seemed like a rhetorical question.