A crackdown on Hong Kong booksellers reflects the deep divides in China’s Communist Party

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

Because of his dictatorial style, China’s president Xi Jinping has lost all of his allies within the Communist Party. As public anger grows over the country’s economic slowdown, it’s an opportune time for Xi’s political opponents to take him down—and former presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao are ready to do so.

So claims 2016: Collapse of the Communist Party of China, a book written in Chinese under the pseudonym Dongfang Liang, or “Bright East.” It was the best-selling political title at Causeway Bay Bookstore, before the store closed down last month after five employees, including owner Gui Minhai, went missing. Gui mysteriously resurfaced this weekend, to make a tearful public confession to an 12-year-old crime—a confession widely believed to have been coerced by Chinese authorities.

The disappearance of Gui and his colleagues, who many believe were abducted by mainland Chinese officials, has sparked international concern about the future of freedom of speech in Hong Kong, and about Beijing’s willingness to violate the law signed when the city was handed over from Britain to China.

These are certainly valid concerns. But the crackdown on publishers in Hong Kong is also a sign that the Chinese Communist Party continues to be deeply divided, academics and publishers in Hong Kong believe, and signals the latest brutal attempt by Xi to silence dissenters within.

That’s because Hong Kong’s “banned books” market serves as a place for the 85 million member strong party, one of the world’s largest and most powerful, to air its dirty laundry. Xi has eliminated some of his most powerful rivals since taking power in 2013, but warring factions inside the party remain, and Hong Kong is serving as their battle ground.

In recent years, the Hong Kong book market has “become an extension of the infighting within the party,” Ching Cheong, a former vice-editorial manager with the Communist Party’s official newspaper, Wen Wei Po, told Quartz. When Hu Jintao became president in 2002, different factions within the party began using Hong Kong publishers to disseminate information and earn political favors, or smear their opponents, Ching said.

Since Xi took office in 2013, the trend has only increased, to the point where half of the books published in Hong Kong seem to be criticizing Xi, while the other half praise him, Ching said. The recent crackdown on Hong Kong booksellers show the ruling party elite will no longer tolerate the political instability these books stir up, Ching said.

The evolution of Hong Kong’s “banned books”

So-called “upstairs” bookstores like Causeway Bay, which sell political titles banned in mainland China, don’t just cater to mainland tourists looking for a thrill read in Chinese they can’t get at home. For decades, they have also served as an outlet for the Communist Party to read about itself, settle scores, and rewrite the official, whitewashed “history” and highly censored “news” available on the mainland. These bookstores’ steadiest customers, and many books’ authors, have been former or current party members.

Hong Kong’s “banned” publishing industry has its roots in journalists with deep knowledge of the Communist Party, who were often members as well.

First published in 1977, Cheng Ming Monthly was the first political magazine in Hong Kong focused on the leadership of the Communist Party. Wan Fai, a veteran Hong Kong journalist, founded the well-respected magazine, after writing for the party’s mouthpiece Wen Wei Po for 25 years.

Although it was quickly banned on the mainland for its criticism of one-party dictatorship, Cheng Ming remains a valuable reference for the party’s high-ranking officials, who buy around 1,000 copies of each issue, Wan said in an interview with the US-funded Voice of America (link in Chinese) in 2002, on the magazine’s 25th anniversary.

Through most of the 1980s, Cheng Ming and its sister publication The Trend kept tabs on the party, with information sourced from party officials, academics, and ordinary people on the mainland, Ching, the former vice-editorial manager at Wen Wei Po, told Quartz.

The situation changed after the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

Many journalists fled the mainland and launched their own magazines in Hong Kong. From monthly magazines, they moved into books, in part because they knew more in-depth information about the Party, Ching said.

Ho Pin’s Mirror Books is a prominent example. Ho, 51, a former journalist with a Communist Party newspaper, left the mainland in 1989, and established a publishing house in Canada in 1991. Mirror published a series of well-known political titles in Hong Kong including China After Deng Xiaoping’s Era, which Ho wrote himself.

The Hong Kong publishing market was highly profitable, thanks mostly to Chinese mainlanders eager for unvarnished news, analysis, and recent history of the country they lived in, that was not available at home. Profits attracted even more publishers, including new players who produce thinly documented books that round up gossip about Party leaders.

Mighty Current, the publishing house in the eye of the storm, is the largest publisher of gossipy titles in Hong Kong, Willy Wo-lap Lam, an adjunct professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, told Quartz, and produced about one-third of those titles in the market in the past five years. It has been lucrative: Gui Minhai, Mighty Current’s founder, reportedly earned HK$10 million ($1.3 million) in 2013.

Before he disappeared in October, Gui specialized in collecting insider-y information on the party leadership, including tales of officials’ mistresses, and recent histories according to officials’ families. He personally wrote about ten books a year, after meeting mainlanders with party connections in Hong Kong’s tea houses, and gleaning first-hand information from them, a friend wrote in Taiwan’s Storm Media (link in Chinese) this December.

History, gossip or both?

The Communist Party’s long history of purging one group of high-ranking officials when another comes to power, and then erasing or diminishing the first from history books or forcing them into silence, has created a situation where once-powerful men became desperate to set the record straight before or after they died.

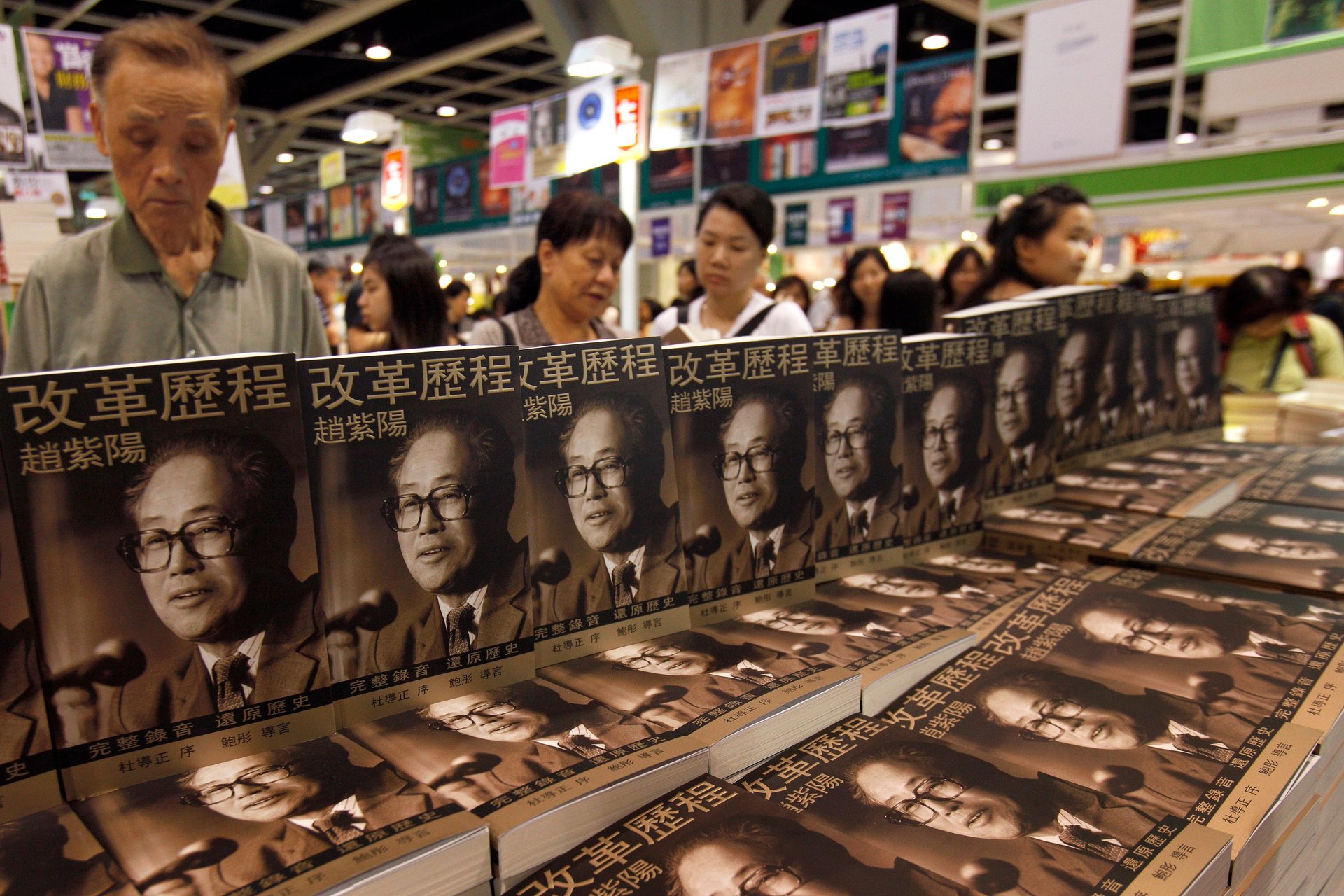

Bao Pu, founder of New Century Press, another Hong Kong publisher, published the secret memoirs of Zhao Ziyang, a former Communist Party general secretary who was purged after the 1989 crackdown. In them, Zhao alleges there was no legitimate vote of the standing committee of the Politburo authorizing the use of military force in Tiananmen. The book was based on hours of tapes smuggled out of Zhao’s home while he was under house arrest.

Bao, who is the son of Bao Tong, a longtime aide to Zhao, said his objective is to publish “reliable materials for historical research, which is crucial after decades of suppression of independent thinking… and the erasing of historical facts from public consciousness.”

Other New Century authors from the party include Hu Jiwei, a former People’s Daily chief editor who was sacked for supporting the 1989 Tiananmen Square movement, Wu Wei, a former Chinese official involved in the failed political reforms of the 1980s, and Du Guang, a former teacher at the central party school.

Books published by Mighty Current and other gossipy publishing houses, on the other hand, have been more focused on current events, and more speculative. Mighty Current’s The House Arrest of Jiang Zemin, for example, claimed former party chief Jiang has been under house arrest in his villa in Shanghai since May of 2015, after he secretly disrupting Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, a rumor that circulated outside China. One month after the book was published, Jiang appeared in public at a grand military parade, standing side by side with Xi on the Tiananmen Gatetower to review troops, essentially shutting down the idea.

Other Mighty Current titles allege China’s folk singer-turned-first lady Peng Liyuan lost her virginity to a man other than Xi, and another folk singer became the “public mistress” of over ten high-ranking party officials, including the fallen security czar Zhou Yongkang. An upcoming book tentatively titled Xi Jinping and His Six Women is believed to have sparked the current crackdown on Mighty Current, and could be politically explosive if it alleges Xi had an affair during marriage, because he has made adultery grounds for banishment from the party.

Paul Tang, owner of People’s Book Cafe in Causeway Bay, has been selling books about Chinese politics for nearly 10 years. Mainland readers mostly want candid books about former Chinese leaders Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, or about the history of the Cultural Revolution and the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, Tang told Quartz.

Still, business was best during the incredibly tumultuous period when president Xi’s rival Bo Xilai, the former Chongqing party chief, was caught in a scandal, and Xi came to power, Tang said. Bo was betrayed by his right hand man who abruptly fled to the US consulate to accuse Bo’s wife of murder. Bo was sentenced to a lifetime in jail with charges on corruption and abuse of power, while Xi, after taking the leadership, started a “rectification campaign” to purify the party.

It was quite possibly the biggest party upheaval in decades, but the news was heavily censored on the mainland. Still, Hong Kong’s booksellers cranked out hundreds of titles on the situation, some supporting Bo’s, and others tearing him down.

Xi Jinping cracks down

Since coming to power, Xi has clamped down on free speech, human rights lawyers, journalists, and activists, while jailing huge numbers of rivals like Bo. The crackdown is part of a “public opinion struggle” in the party’s ideological work, aiming to promote its core socialist beliefs and banish values that counter them, Xi explained in Aug. of 2013—but there are many who believe it is also a way to wipe out dissenting voices inside his own party.

The backdrop to the crackdown on Hong Kong booksellers is “the struggles within the party,” Margaret Ng, a former pro-democracy lawmaker, barrister, and writer in Hong Kong, told Quartz. “That has been discussed in Hong Kong for many months, our feeling is it is still going on.”

While Mighty Current has dominated the news, the crackdown really started years ago. The first Hong Kong publisher known to be nabbed by the mainland authorities was Yao Wentian, chief editor of Morning Bell Press, who was preparing to publish a book titled China’s Godfather Xi Jinping, written by exiled Chinese author Yu Jie. The book criticizes Xi as a dictator, comparable to famous patriarch in the Italian-American Mafia trilogy.

In October of 2013, the then 73-year-old was held by Shenzhen police after he paid a visit across the border, and later formally arrested on charges of smuggling bottles of industrial chemicals back in 2010. In May of 2014, Yao was sentenced 10 years in jail.

China’s Godfather Xi Jinping was later published by Open Books in March of 2014.

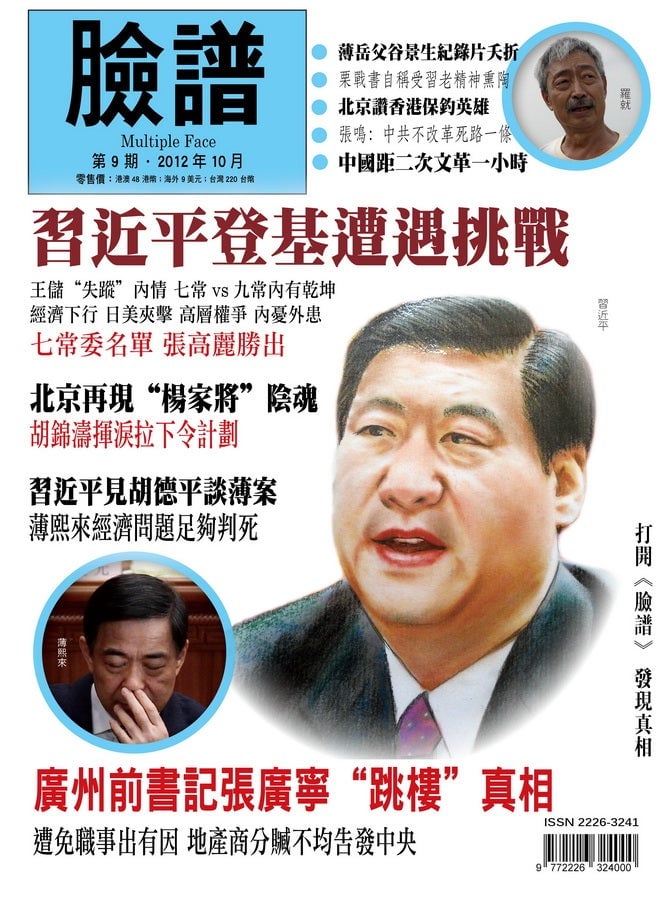

In May of 2014, a pair of Hong Kong journalists behind two political affairs magazines Multiple Face and New Way Monthly were taken away by police from their homes in Shenzhen. The magazines has questioned Xi’s rise to power. After being detained for more than 17 months, publisher Wang Jianmin and editor-in-chief Guo Zhongxiao pleaded guilty to “running an illegal business” before a Shenzhen court after sending the magazines to eight friends on the mainland.

“We published unverified news and have tarnished the image of the party and the government,” Guo said at the trail.

Hong Kong’s bookstores self-censor

In early 2015, central authorities issued instructions to the police and state security units “regarding silencing and eradicating publishers in Hong Kong which are putting out ‘anti-China’ and ‘destabilizing’ political materials,” Lam said, citing sources in Beijing. Since then, “state security personnel have visited Hong Kong publishers in person warning them not to publish certain books.”

Though Hong Kong is technically guaranteed the right to free speech, press, and publication by the “Basic Law” that covers the city, self-censorship is spreading. Commercial Press, one of the three major local publishers who are ultimately owned by Beijing’s representative office in Hong Kong, has withdrawn books banned on the mainland from sale, local newspaper the Standard reported.

Page One, the Singapore-based international retailer who owns eight outlets in the city, began to stop selling sensitive titles in late November, around the time the first of the five linked to Causeway Bay Bookstore went missing. Now, Page One is no longer carrying books about the Communist Party at all, according to a memo circulated this month.

This month, Open Books pulled a planned sequel to the book comparing Xi to a “godfather,” Xi Zinping’s Nightmare. “Circumstances have changed, and I am not able to face the huge consequences,” Open’s chief editor told the author Yu Jie in a letter.

What happens next?

The late December disappearance of Lee Bo, the fifth Causeway Bay Books employee to disappear, caused huge concern in Hong Kong and out. Thousands of protesters took to Hong Kong’s streets on Jan. 10 to demand the release of Lee and to declare the “one country, two systems” principle.

Gui’s reappearance in Chinese custody seems to have confirmed many people’s worst fears. Although he said in his confession he voluntarily returned to China, concern remains that he was kidnapped or forced. Because he is also a Swedish citizen, the Swedish government is stepping in, and has reportedly summoned China’s ambassador in Sweden to discuss the case.

Meanwhile, demand for books in Chinese about the party is not going away even as Beijing cracks down. Ho, the publisher, said he has been preparing for this new pressure for decades. His editorial team is based in the US and Europe, and his translation team in Taiwan. The staff in Hong Kong only works with local distributors. “They [the party] cannot find a person in Hong Kong to affect Mirror’s contents,” Ho said. “Even our art production is not done in Hong Kong.”

“Of course this is scary,” said Tang of the People’s Book Cafe in Causeway Bay. But even if the mainland authorities shut down the whole market in Hong Kong, “they can’t control the whole world,” Tang said. Already in nearby Taiwan, sales of Chinese-language books banned on the mainland have increased five-fold since the crackdown on Hong Kong booksellers.