Hong Kong

On June 16 Hong Kong witnessed a remarkable news conference in which a local bookseller said he had been kidnapped by mainland Chinese authorities. Lam Wing-kee said that upon visiting the mainland in October 2015, he was handcuffed and blindfolded by authorities, and taken to the city of Ningbo, where he was held in a small room and asked to sign a declaration stating he would give up rights to contact his family and not seek assistance from a lawyer.

His crime? Authorities accused Lam of illegal business operations. Lam worked at Causeway Bay Books in Hong Kong, which sold books about China’s Communist Party, and was planning one on the love life of Chinese president Xi Jinping. Another title that became a bestseller was about the upcoming collapse of the China’s ruling party. One by one, five employees of the store went missing, also charged with illegal business operations.

The authorities forced Lam to express regret for his supposed crimes on camera, and then they broadcast the video on Chinese television. They let him return to Hong Kong this month provided he retrieve and turn over a hard drive containing information about Causeway Bay Books’ readers and authors. But instead of obeying them and returning to the mainland with the information, Lam spread the word about his detention and treatment to the Hong Kong media.

Lam’s surprise revelations have stirred up heated debates about the validity of the Hong Kong’s autonomy within its autocratic “fatherland.” When Hong Kong was transferred from British to Chinese rule 1997, China agreed to a “one country, two systems” setup in which Hong Kong would retain its “basic law”—a sort of mini-constitution—and keep its legal system, parliamentary system, and people’s rights and freedom (including freedom of expression) for 50 years.

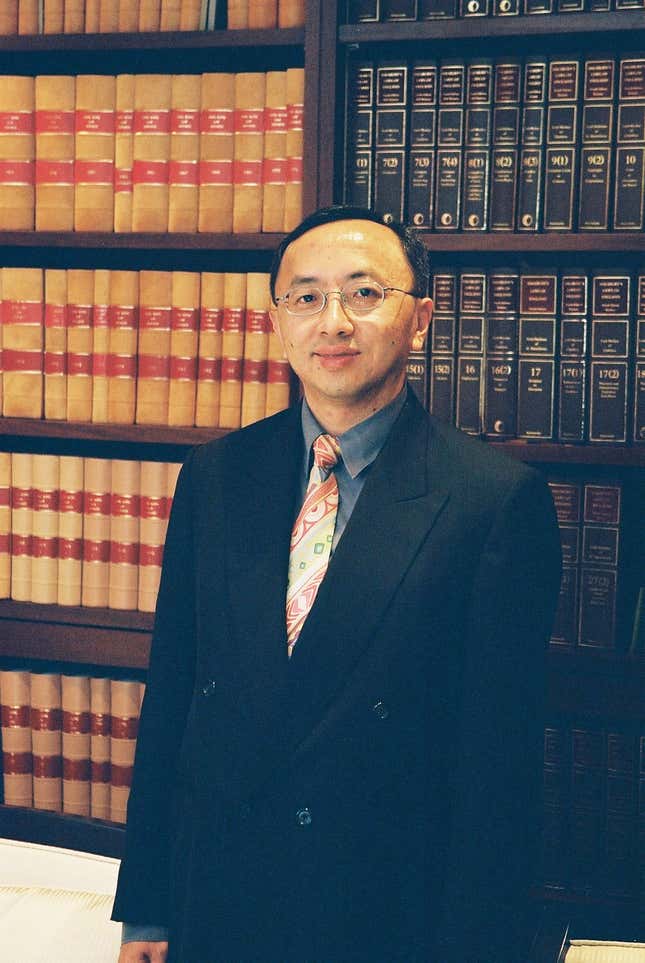

The abduction of Lam and his colleagues throws all of that into doubt, as have other incidents in recent years, including the brutal beating of a pro-democracy demonstrator in 2014. We interviewed Eric Cheung, a prominent legal scholar from the University of Hong Kong, about the legal implications of Lam’s treatment.

How would you define the idea of the “rule of law”?

There isn’t a simple way to define it—each scholar has their own interpretation. Yet, there are some basic concepts that can never be excluded when talking about it.

First, that everyone is equal before law. Even as a power-holder, you are still subject to the law, like all the others.

Second, that the powers of the government are restricted. It is to ensure that their powers will not be abused.

Third, that there’s an independent judiciary to interpret the laws. If the administration can interpret the laws themselves, they will of course never find any of their own actions illegal.

Is the rule of law practiced well in Hong Kong and in mainland China?

One of the advantages of Hong Kong is our profound foundation of the rule of law. What we have here is not just the “hard” legal system. It also consists of a “soft” part: values. That is, everybody accepts and acts according to a certain norm to an extent that there is no need to doubt it.

Take the “independent judiciary” requirement as an example. Us scholars often use one simple question to judge this: When a court issues a judgement on a case, will there be anybody doubting that the judge has been bribed?

I believe most people in Hong Kong would not consider this a possibility. We might question a judge’s decision, but bribery or political interference—like a party secretary or a high-ranking official instructing a judge—is unimaginable, or simply not a possibility in our minds. This confidence and trust in the system certainly says something.

However, if we ask the same question about the mainland, then the answer might be different. There, the government’s power is basically unrestricted. Everything, from the interpretation to the enforcement of laws, is decided by the government. They are still quite far from achieving the rule of law.

Do you think what happened to Lam and the other booksellers is in accordance with the ideals of the rule of law?

I’m afraid not. It reveals some problems other than judiciary independence.

First, the forced confession of his crimes. In any society with a mature legal system, one should not be forced to confess his crimes, be it under threats or bribes.

Second, the broadcast of his confession on TV even before the trial starts. This is exactly what we call a “conviction without trial.” Under the rule of law, this should not be possible as this might affect the court’s decision in the future. Yet, this seems to be a very common practice now in mainland China.

Here we see that criminal procedures in mainland China are not really fair and open. Law-enforcing departments are easily indulged to abuse their powers so as to force the suspect to confess, leading to a higher chance of miscarriages of justice. This is not uncommon in the mainland: There are cases where the convicted is found to have confessed to false charges under torture, only after spending 10 or 20 years in jail; and in worse cases, after they had already been sentenced to death.

Although what happened to Lam was in the mainland, does it have any implications for Hong Kong?

There is one important point that caught little media attention: The general line of the pro-Beijing camp is that “Lam’s store is in Hong Kong, but he sold and sent books to the mainland, breaking mainland laws and so was arrested in the mainland.” They thus argue that it has nothing to do with the “one country, two systems” arrangements. However, is that true?

Here is the question: When one’s actions in Hong Kong are perfectly legal according to Hong Kong laws but are illegal in the mainland and have an effect there, are they subject to the mainland law? And can one be arrested accordingly when going to the mainland?

To answer this, we must have a clear understanding of the Basic Law (Hong Kong’s constitution).

The Criminal Law of China states that it is still applicable to Chinese citizens physically outside the mainland; and according to China’s definition of nationality, Hong Kong citizens with Chinese ancestry are also considered “Chinese citizens.”

However, the Basic Law states clearly that in Hong Kong one is only required to obey Hong Kong laws and a certain mainland laws like those related to diplomacy and national security as listed in its annex. The criminal law is not part of it.

In fact, the Basic Law is—although many people don’t know about it—actually more than a local law. It is a national law passed by the National People’s Congress (the Chinese equivalent of a “national parliament”). Therefore, this status ensures that it would not be overridden by any other national laws of China—including the criminal law.

Now, if we accept this “consequentialism” argument—whether an action has an effect in mainland China—as a principle in judging whether the Chinese law is applicable to a Hong Kong citizen’s action in Hong Kong, it will be a serious violation of the Basic Law and thus “one country, two systems.”

If the “consequentialism” argument is upheld by the local court, how would it impact the legal system in Hong Kong?

If so, the rule of law would be gone.

Any actions could have some so-called “effect” in the mainland: something that you say, some articles that you write, or some demonstrations and rallies that you join… Who will ever be “safe” and “innocent”?

The Chinese government might say “I won’t arrest everybody,” but this is exactly what’s wrong—I have no idea whether or not you will suddenly change your mind and arrest me!

If we take a closer look at the Lam case, they don’t even have one article that clearly states what Lam did was illegal. They simply called it “illegal operation of bookstore.” But how was it illegal? And those banned books, why are they banned?

If the criminal law of China is applicable in Hong Kong, people will need to avoid violating it. But honestly, how? Chinese authorities have been “enforcing” their laws arbitrarily to whoever they want to arrest.

Clarity of laws is important in the rule of law. Laws should be clear and easily understandable for citizens, so that they can know if they have committed an offense, and take the consequences if that’s the case.

However, the arbitrary and unrestricted discretion of the government in the Chinese system is completely against this and will impact the Hong Kong legal system adversely.

Will it affect some other aspects of Hong Kong as well?

Certainly, everyone will be affected. Take business as an example.

In mainland China, somebody who’s involved in a business dispute often gets accused of fraud or extortion, regardless of whether they actually did. They then get arrested by the police and won’t get released until they pay the money to the other side. This happened to many Hong Kong businessmen in the mainland before. Still, we can say that in these cases, the business itself is done in the mainland so they involve actual “actions” there.

What if actions in Hong Kong with effects in mainland China are also covered? If a mainlander accuses a Hong Kong company for defrauding him in Hong Kong, you affected a mainland citizen and so the Chinese law will apply and you are thus at risk of arrest whenever you go to the mainland.

If this happens, would Hong Kongers still dare to go to the mainland? In this way, many ties between Hong Kong and mainland China will surely be affected, from commerce to culture.

How do you see the future of the rule of law in Hong Kong?

Us Hong Kongers need to put up our guard and be on alert, and cherish our hard-earned rule of law. What’s worrying to me is that some Hong Kong people seem to be “mainland-izing” our legal system here.

When I went to a public forum about the Lam case, an audience member asked: “Who are Lam and Lee [a colleague at the bookstore] to talk about ‘rights’ when they have broken the law?” Surprisingly, the person who said this was not from the mainland—he was from Hong Kong.

Never mind the fact that what they did was perfectly legal in Hong Kong. Even if it wasn’t, you won’t lose all your basic rights when you become a suspect—at least not in Hong Kong.

Unfortunately, these voices are getting louder, and it seems like more and more people are embracing such values. I really hope Hong Kong can stay firm and defend our mature legal system and the rule of law, so that one day, mainland China will gradually keep up with us. I hope it’s not the other way round.