The brutal beating of a Hong Kong protester puts the city’s famed “rule of law” on trial

HONG KONG—The pro-democracy protests that have gripped Hong Kong for more than two weeks have already raised serious questions about the strength of the city’s much-vaunted “rule of law,” and who Hong Kong’s police and governing officials truly serve: Communist party chiefs in Beijing, or Hong Kong citizens.

HONG KONG—The pro-democracy protests that have gripped Hong Kong for more than two weeks have already raised serious questions about the strength of the city’s much-vaunted “rule of law,” and who Hong Kong’s police and governing officials truly serve: Communist party chiefs in Beijing, or Hong Kong citizens.

Now a widely-circulated video taken early this morning, showing a group of police pummeling an already-restrained pro-democracy politician during a violent crackdown on protesters, has thrown those doubts into high relief. Within hours, the incident sparked outrage in Hong Kong’s legislative council, was condemned by Amnesty International, and drew comparisons on social media to the beating of Rodney King that started the Los Angeles riots of 1991.

The video, taken by TVB, Hong Kong’s usually pro-Beijing public television station, shows a protester with his hands apparently tied behind his back, being taken into a dark corner of Tamar Park and thrashed as he lay on the ground:

The man was quickly identified as Ken Tsang Kin-chiu, a politician with the Civic Party and a social worker who helps street children (paywall). Occupy Central, one of the groups organizing the protests, posted photos of his injuries on its Facebook page:

Tsang has been a long-time critic of Beijing. In 2012, Tsang reportedly interrupted a speech by China’s then-president Hu Jintao in Hong Kong by yelling “Justice for the Tiananmen massacre! An end to the single-party rule,” before being dragged away. He was not arrested at the time.

What Hong Kong stands for

Reliable, tough policing and adherence to well-established and public legal guidelines are some of the mainstays of Hong Kong. Another is the city’s ”Basic Law,” a mini-constitution that guarantees certain freedoms not available in mainland China, including free speech, an independent media and—most importantly for the protesters—the promise of universal suffrage. Together, the mix draws thousands of international companies that make Hong Kong their base to do business with China, and has earned the city top marks on rankings of international economic freedom.

But critics say these standards are slipping, most notably in the police department.

“The judiciary side is really holding up their principles,” Cassian Cheung, the chief executive officer of NextMedia, told Quartz. “We have seen, however, a deterioration in the law enforcement side.” NextMedia has seen this first-hand as the publisher of Apple Daily, a pro-democratic newspaper. The company has been harassed recently by pro-Beijing groups blocking distribution trucks from leaving its plant.

Despite a High Court judge’s injunction issued Oct. 14, that barred protesters from blocking Apple Daily’s distribution and citing the importance of a “free press,” protesters continue to block the paper’s trucks with little police interference. Even though some “groups show abusive behavior” Cheung said, “you never see the police go after them. It’s hard to say there’s no bias.”

Long-time veterans of Hong Kong’s legal system also see some shifts. “There is some evidence of a desire among certain senior officers to impress Beijing if they can,” Keith Oderberg, a criminal lawyer and former senior prosecutor who has practiced in Hong Kong since 1981, told Quartz. Beijing is believed to keep a very close eye on powerful people in Hong Kong, which encourages some Hong Kong justice officials, bureaucrats, and police to try to perform as they would if they were in China, he said.

Take the experience of the student protest leader Joshua Wong, who was arrested just as the protests started in late September. Although Hong Kong law requires detainees to be charged or released within 48 hours, the police were “uncooperative and obstructive,” said Oderberg, who as part of a team of lawyers acting pro bono, represented Wong and two other students. Senior officers didn’t answer their phones, much less provide information about the charges against the youthful activist or where he was being held. Wong and the other two were freed only after the case was brought before a High Court judge, after about 43 hours in detention.

Improvised and ineffective

The recent protests present a formidable challenge for Hong Kong’s uncomfortable pairing of a Beijing-loyal chief executive who is often criticized for his weak leadership at home, and the nearly 30,000-strong police force drawn from the city’s local population.

Police first reacted to the peaceful protests with tear gas, inspiring thousands of additional protesters to take to the streets. Then, rather than negotiating with the crowd that numbered in the tens of thousands or even calling on police to forcibly arrest them (a potentially unpopular but certainly lawful option), CY Leung and his administration have issued tough statements, and usually failed to follow up on them, from his British colonial era mansion (paywall).

In the power vacuum, Hong Kong’s central business district was transformed for more than two weeks into a joyful democracy carnival—albeit one that created massive traffic snarls and inconvenienced millions, as well as hurting local businesses. But police also appeared to mostly stand by as groups of masked men, triad strongmen with suspected links to Beijing, and other anti-Occupy forces manhandled protesters, attacked journalists, and in one instance even brought an unmarked crane to clear protest barricades themselves.

Things came to a head last night and early this morning, after a group of protesters created a new block on a road adjacent to the chief executive’s office, after at one point surrounding police trying to remove them. Police responded with pepper spray, violently dragging some protesters away from the scene, arresting dozens, and then beating Tsang.

“The fact is somebody has been beaten up and more than 40 have been arrested. It’s really bad,” pro-democracy legislative council member Emily Lau told Quartz today. Asked if the crackdown was a symptom of a breakdown in the rule of law, she answered: “Of course … Without rule of law, our civil liberties will be at stake. People always look to law enforcement to be independent, so people are worried.”

Whose fault is this anyway?

Hong Kong and Chinese authorities have couched their arguments for an end to the protests on the basis of upholding Hong Kong’s rule of law. They blame the protesters for holding the city hostage and undermining the legal system.

China’s state-run newspaper, the People’s Daily, published an editorial calling the demonstrations “political blackmail” that is destabilizing the city. “Democracy must have a foundation of rule of law. It cannot be a tyranny of the few,” the unsigned editorial said.

The Hong Kong lawmaker Regina Ip, of the pro-Beijing New People’s Party, said in an editorial published on Sunday that the young protesters “don’t seem to live in the real world.” Their demands, that Hong Kong citizens be allowed to nominate their next chief executive, rather than have nominees chosen for them, are impossible, she implied, writing, “All they have is passion, chasing over-simplified ideas and ideals which cannot be turned into reality in the Hong Kong context.”

But other than reiterating that idealistic protesters can’t win, Beijing and its supporters have been short on solutions to the standoff. Instead, Beijing has blamed the protests on Western support, including from groups like the National Endowment for Democracy (which NED categorically denies). And today Leung canceled his quarterly Q&A session with Hong Kong lawmakers, scheduled for tomorrow, citing “security and risk assessments”—a signal that he won’t even entertain inquiries from his closest peers.

Civil unrest is rising

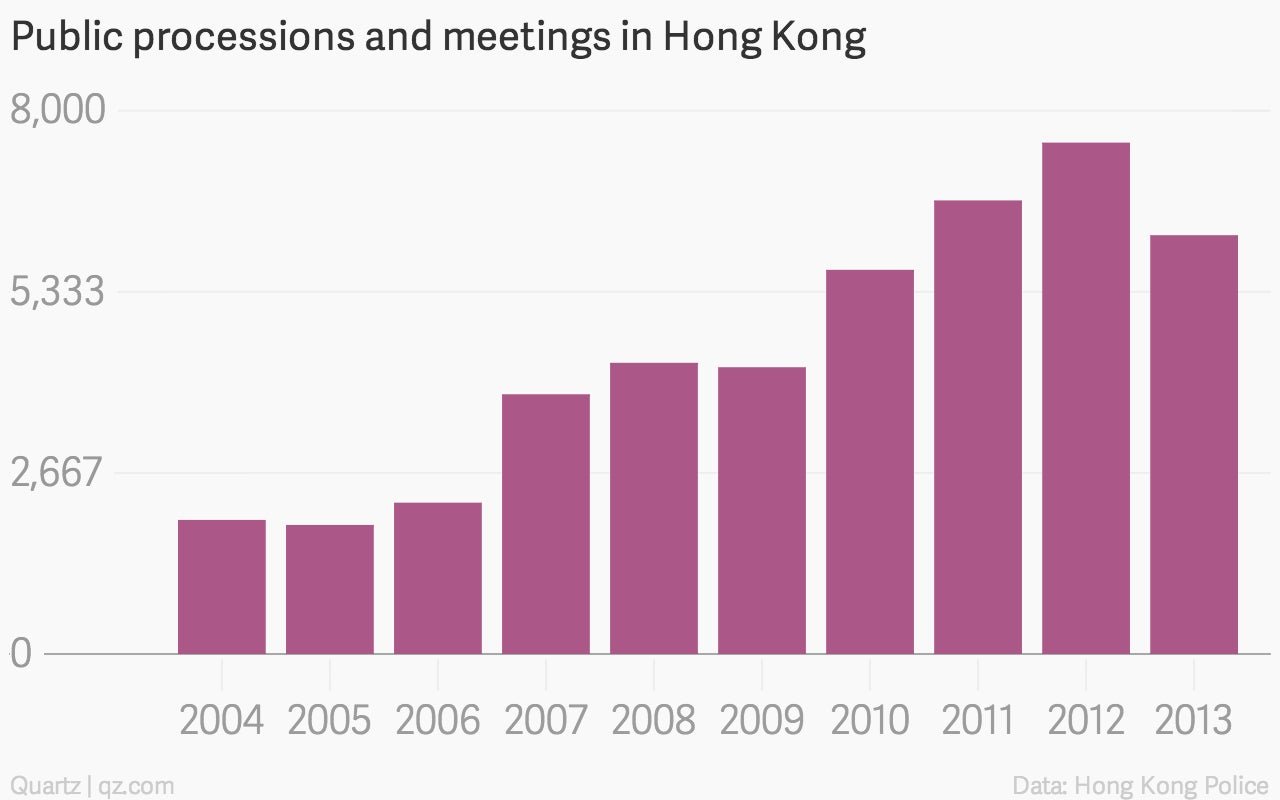

Hong Kong’s administration could have arrested protesters under a public order ordinance that was strengthened in 1997 by Beijing to prohibit gatherings that threaten “national security” and any processions of 30 or more people that haven’t applied for a permit a week before hand. Despite these tough rules, the number of public processions and protests in Hong Kong has tripled in the past decade, according to police data:

The police force and its budget are growing as well—annual spending increased (pdf, pg. 2) from HK$11.5 billion in 2008 to HK$14.6 billion in 2013. And, so have arrests at public events. “In the past few years, there has been a significant increase in the number of cases involving disturbance of order or other unlawful acts during public order events,” said Hong Kong’s secretary for security in 2012.

Nonetheless, Hong Kong remains one of the most crime-free cities in the world, on a per capita basis, bested only by Singapore in a recent comparison (pg. 6).

Fear of the police

Earlier this week, Hong Kong police described their actions to clear barricades from protest sites as “光明磊落” a Chinese idiom that means “open and candid.” After the video of Tsang’s beating was widely circulated on social media, police quickly issued a “clarification,” saying:

Police express concern over the video clip showing several plainclothes officers who are suspected of using excessive force this morning (October 15). Police have already taken immediate actions and will conduct investigation impartially. The Complaints Against Police Office has already received a relevant complaint and will handle it in accordance with the established procedures in a just and impartial manner.

Later, Hong Kong’s Secretary of Security seemed to confirm the video’s veracity, saying the “officers involved will be removed from their current duties.”

The relationship of Hong Kong’s residents with the police may never be the same. Kaka Tang, 30, a nurse in Hong Kong, says she had always had a positive view of the police until now. “In my mind, the police are for protecting the citizens, not just the people at the top,” she said. “I thought, if you are the one that is supposed to protect us, you are not going to hurt us.”

But in response to last night’s police violence, one blogger wrote on a local discussion forum, “Hong Kong’s rule of law is dead.”