Our insatiable appetite for digital video—preferably streamed on-demand—has quietly reshaped the internet.

Consider this: Video currently accounts for 70% of all internet traffic, and that could hit 90% in 2020, according to one widely used forecast by Cisco. On any given day in North America, 40% of peak-time internet traffic flows from Netflix, network gear vendor Sandvine has found. Viewers are lapping up the over 800,000 minutes of video that flow over the internet per second each day. Nielsen has estimated (pdf) that in the first quarter of 2016, people aged 18 to 34 spent nearly 21 hours a week watching television—but they spent 30 hours weekly on smartphones, tablets, and other digital devices, with video occupying most of that time.

Video is basically eating the internet.

A big reason why that’s happening is a rapid expansion in a special kind of infrastructure that gets viewers their video interruption-free. These are content delivery networks (CDNs), private networks owned by the world’s biggest tech companies—Facebook, Google, Apple, Netflix—and a handful of firms that specialize in their operation, that run in parallel to the internet’s core traffic routes. The shift has been so pronounced that nearly half of all traffic flowing over the internet today actually traverses these parallel routes, according to data from research firm TeleGeography.

It’s a fundamental change to the way data has been routed over the internet for decades, which was classically conceived of as a tiered hierarchy of internet providers, with about a dozen large networks comprising the “backbone” of the internet. The internet today is no longer tiered; instead, the experts who measure the global network have a new description for what’s going on: it’s the flattening of the internet.

“Nobody is even aware that the internet has flattened,” says Nishanth Sastry, a professor specializing in the study of content distribution at King’s College in London. “It happened even without people noticing. We changed Big Ben and nobody noticed.”

The internet’s new, flattened structure means content owners like Google and Netflix have more power than ever to control how their content reaches the end-consumer. That rewired internet has led to an intensifying struggle between the web’s biggest companies and the legacy carriers who own the pipes; greater pressure on small access providers to get streams to their rural customers; and made it harder for content companies to compete without their own privileged CDN pathways. Ultimately, consumers could cede more choice to a small number of companies who own both the content on the internet and the means to deliver it.

Trying to stop buffering…

Video traffic exploded in the mid-2000s. It made up 12% of all traffic in 2006 (pdf), but by 2010 it became the largest category of internet traffic, according to Cisco (pdf). That’s because video pre-2005 wasn’t a very good experience. It was grainy, there wasn’t much of it to watch, and it was always buffering—when a video stops and starts as it tries to load more data during playback. Video buffering was so annoying that people simply didn’t watch much internet video. Getting rid of buffering was the key challenge for the internet’s video purveyors.

Work progressed quickly. By 2008, Google was confident enough to start delivering live video streams on YouTube. That’s thanks to CDNs. These networks get video to flow smoothly by reducing the distance it has to travel to a viewer. In the language of computer scientists, it’s placing the content closer to the network’s edge. Google says it has spent “billions” building this infrastructure, although it doesn’t disclose these numbers in public filings. Google declined to comment for this article.

To understand how CDNs work, it’s useful to take a step back and think about the classical model of the internet. Sastry uses the analogy of air traffic to explain it. You might imagine the internet as air-traffic routes, with data-packets as the airliners. The classical model of the internet has airliners flying between airports in a hub-and-spoke model. If you wanted to get from Anchorage, in Alaska, to Cannes, in the south of France, you might first fly to a hub like Chicago, followed by a bigger hub like London, and then a final short-haul flight to Cannes.

In this model, each airport represents a different tier of the internet infrastructure. At the bottom are the consumer ISPs—the Anchorage airports of the world—who send their traffic on to larger networks, perhaps a tier-three provider. The traffic ascends up the hierarchy of tiers until it hits a tier-one network—the so-called “backbone” of the internet. From there, the traffic is passed on to more and more localized networks until it reaches its destination.

Those big airport hubs, the internet backbone, are made up of about a dozen sprawling networks that have been around more or less since the internet itself was made commercially available in 1995. These networks own and operate the fiber-optic or copper cables that data flows over. Over time, these networks grew larger, and interlinked with one another—usually for free, in a process called peering—so that data could flow more efficiently around the world. They’re owned by giant telcos such as AT&T and Deutsche Telekom, as well as firms like CenturyLink.

The internet got too big

As the internet exploded in popularity, data had to travel across more and more networks to get to its destination. That meant certain types of content, like video, which required a constant flow of data packets, couldn’t reliably be streamed over that distance. Non-video content, like text and images, fared better. In this model, when a viewer requests a video from, say, YouTube, the data has to travel from the YouTube server to the viewer’s computer. If millions of viewers are requesting videos at the same time, the YouTube server can get overwhelmed, and the networks get jammed up, resulting in the dreaded buffering.

“Every [data] flow would go from the smaller end-consumers to slightly bigger ones like Virgin Media and BT, to other ISPs, to AT&T, and then back down to the other end,” says Sastry. “But that’s too long a route. The internet became bigger and bigger, the number of hops became larger and larger, so you can’t get the kind of guarantees for video distribution you need.”

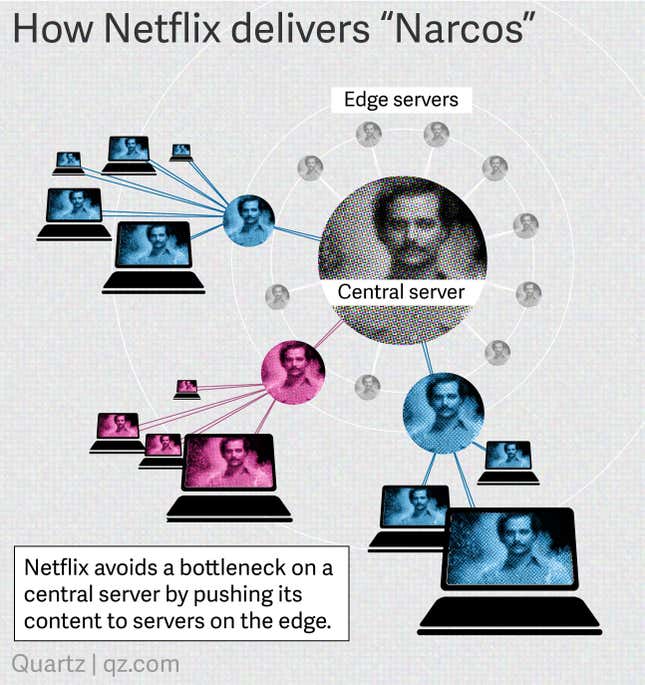

CDNs change all that by dramatically shortening the distance a packet of data has to travel to reach its destination. With a CDN network, data rarely has to ascend to the internet backbone; instead it skirts around it—the network’s edge. CDNs pull off this trick by spreading their content around the globe instead of relying on a central server.

In a CDN system, a Netflix server, for instance, might deliver all of Narcos season two to hundreds of other machines scattered around the world at an off-peak time. This ensures that the initial delivery is smooth. Those dozens of other machines are directly peered with consumer ISPs—a Virgin Media, for example. That means there are literally Netflix machines connected by cables to servers owned by that ISP, usually housed in that ISP’s data center. Once Narcos is initially transferred, the Netflix machine maintains a copy of it. When the season premiers, the video is already primed; it simply has to flow from the Netflix machine in the Virgin Media data center to the viewer. It didn’t have to travel all the way from Netflix’s central server.

YouTube flattened the internet

That’s a simplified description of how Netflix gets its video to you smoothly. But the company built such a system in 2012, called Open Connect. Firms that control the videos, like Netflix or YouTube, didn’t invent the CDN. Such networks have been operated by behind-the-scenes firms like Akamai, Limelight, and Level 3 since the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Companies like Netflix and Google did change the networking landscape in one important way: They were content owners who also started to build their own CDN infrastructure. This is a departure from the customary split between the companies that made the content (say, eBay or Yahoo in their glory days), and the companies that transported that content to the consumer. Video is hugely important to the content owners. YouTube, for instance, doesn’t contribute much to Google’s bottom line currently. But analysts believe it could add a lot to the search-engine’s growth in the next five years.

The shift to content owners building their own CDNs was triggered by YouTube and Google. After the search giant acquired the video platform in 2006, its top task was to address complaints about—you guessed it—video buffering. Google began investing more in extending its own already considerable CDN to deliver YouTube videos to users more quickly. In 2009, Google accounted for over 5% of internet traffic, according to a seminal study (pdf) on the subject (more on that later). ”Google bought up a lot of fiber when it suddenly became cheap, now they have one of the biggest backbones going under oceans, going across continents, and so forth. That allows them to side step these tier-one ISPs,” Sastry said.

The phenomenon was first documented in 2008, in a paper titled The Flattening Internet Topology: Natural Evolution, Unsightly Barnacles or Contrived Collapse? (pdf). In that paper, four researchers from HP Labs, the University of Calgary, and the Indian Institute of Technology found that several large internet companies–content providers like Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo–were building their own large-scale private networks. The research was a starting point, and it was almost incredulous in its conclusion:

“Our data suggests that the Internet topology is becoming flatter, as large content providers are relying less on tier-one ISPs, and peering with larger numbers of lower tier ISPs … only time will determine if this ‘mutation’ becomes the new ‘norm,’ or an ‘abomination’ which will eventually die off.”

The authors suspected that the long-held model of a multi-tiered internet, where different networks each played a part in shipping traffic to one another over a shared, global internet, was now being replaced by private networks owned by content companies.

They identified potential problems with this new arrangement: smaller content providers could face higher barriers to entry, the tier-one providers might have to consolidate, and users might be faced with reduced choice in content in the long run. The paper recommended a study to fully quantify the phenomenon. Two years later, the researchers’ question had an answer.

A study by Craig Labovitz (pdf) and others at Arbor Networks and Jon Oberheide and Farnam Jahanian of the University of Michigan was able to measure the internet’s suspected flatness for the first time. The results were significant. “We argue the internet industry is in the midst of an inflection point out of which new network engineering design, business models and economies are emerging,” the authors wrote.

It was now clear that content owners like Google didn’t just own the content, they also distributed it. As Arielle Sumits, the researcher who leads work on Cisco’s report, put it, the tech giants are “gaining control over not only the content but the means of transferring the content.”

A flatter world isn’t always better

The flattened internet gave us free-flowing video streams, but at what cost? One way to think about it is this: If the “shared” internet—the bits connected by the tiered hierarchy—disappeared tomorrow, you’d still be able to get your Narcos fix or Apple TV stream, or the services of a handful of other giant companies, with a bit of elbow grease and duct tape on the back-end. That’s great for users who can afford the subscriptions, and the companies who can afford the CDNs; not so good for everything else on the internet. In other words, the flattened internet is also one in which a few tech firms are dominant. “Video is not flowing across the internet [now],” says Sastry. “[CDNs] are a hugely expensive way of doing things, it misses opportunities for sharing the network, it leaves a lot of people behind.”

Sastry’s talking about one side-effect of a flat internet, which is to hasten the demise of small, independent, ISPs. These so-called mom ‘n’ pop ISPs used to be a common feature of the network access landscape. Not anymore. In most developed internet markets today, a handful of large ISPs are dominant, partly because they can peer with the CDNs run by video-providers and thus promise their customers the speedy video access they demand. Sastry’s research shows that in the UK, the top eight ISPs account for over 70% of all traffic.

The problem with big ISPs is that it leaves some users underserved. In the US, for instance, a massive consolidation of wireless ISPs (WISPs), is underway, according to Alex Phillips, president of the WISP Association. These providers tend to be the on-ramps of rural or suburban areas, where population density is low, and thus unprofitable for wired-access firms.

About 3 million subscribers use WISPs in the US. Companies like Rise Broadband have acquired 112 other WISPs in the last 10 years, with plans to buy more. The largest WISP has about 150,000 subscribers, but the next largest provider has about a tenth of those numbers, Phillips says.

But the rise of streaming video means that users in the countryside, or in mountainous areas, want their Stranger Things fix too. That’s putting pressure on the small WISPs, who can’t always afford to deliver that amount of traffic to their customers. “A customer used to have a 1.5 meg connection and use it occasionally during the day,” says Phillips. “Now they’re using it for hours—and in some cases all day—it’s having a burden on our network, requiring us to buy more bandwidth.”

The solution for a WISP is to peer with a CDN to bring costs down, and improve performance. But that’s not always financially feasible when you have a subscriber base numbering in the thousands. “It comes back to cost,” says Phillips, who also runs a WISP with 3,000 subscribers in Virginia. ”I’ve looked at the cost of peering, and it seems to me like it costs the same as buying a 1 gig internet connection, so it’s never been that cost effective for us.”

For instance, Phillips says, if a WISP had to choose between an additional internet connection, or a peering connection, picking the internet connection would be prudent, since it provided redundancy. But if consumers demand buffer-free video, the costs for WISPs go up. ”You need to be a certain sized company to justify the transportation costs to peer with another service provider,” he says.

Phillips has avoided raising fees for his customers so far, but says rates would go up three to five times if he passed on all his costs to subscribers. “More competition, more choice, is better for the consumer in the long run,” he says. “We’ve weathered three competitors who’ve come and gone in our area.”

Redecentralizing the web

There are other, murkier downsides of this concentration of power on the internet. For instance, the same handful of tech companies dominate both the infrastructure of the internet, and its most popular application—the World-Wide Web. The web’s inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, has embarked on a multi-year campaign to try to “redecentralize” the web, to bring its equalizing design to bear on what he sees as monopolistic forces leading to a single company dominating sectors like social networking or search.

“The web is already decentralized,” he told the New York Times. “The problem is the dominance of one search engine, one big social network, one Twitter for microblogging. We don’t have a technology problem, we have a social problem.”

While the “redecentralize” campaign has garnered the support of the usual groups of net rights advocates, it hasn’t caught on with the public at large. It’s difficult to rally people around their rights in virtual space and the dynamics of ownership of the invisible infrastructures that the internet runs on.

Maria Farrell, a former senior executive at ICANN, the organization that runs the internet’s domain-name system, points out that the picture is largely obscured to the man on the street. ”The average user is thinking, this is great I can watch football,” she says. “But in the medium to longer term there is certainly a serious risk of local content providers being crowded out. … This vertical integration leads to a set of global monopolies in social media, in search, in content provision.”

Even the staunchest digital-rights defenders aren’t quite sure what to make of the consolidation of power in a flattened internet. Joe McNamee, executive director of European rights group EDRi, says even if content owners are building their own parallel infrastructure, they’re in the clear so long as their efforts to integrate vertically don’t extend to controlling the “last mile” of internet access. At that point, they might run afoul of net neutrality rules, which dictate that providers can’t favor some forms of data over others. “What’s going to happen when you have both that CDN infrastructure and last-mile access like Facebook and Google are aiming for? Then you end up in another world,” McNamee says.

That said, some content providers have made a point of telling consumers just how much better off they would be if they got their internet access from an ISP that was hooked up to their CDN network. Netflix maintains its ISP Speed Index so consumers can look up which providers give the fastest speeds for Netflix streams. In the UK for instance, Virgin offers the fastest speeds and EE, the slowest. While Netflix doesn’t say which ISPs it peers with, a June 2016 paper (pdf) by Queen Mary University researchers detected 41 Netflix servers deployed with Virgin and none with EE.

Netflix has clashed with large ISPs in the US, demonstrating just how murky issues of power and money on the flattened internet can be. In 2014, it started a war of words with Verizon, which it accused of throttling Netflix traffic to its customers. The charge was that Verizon was using its power to block its customers from getting the Netflix service they’d signed up. Verizon, on the other hand, said it was Netflix who was abusing its position as a heavyweight sender of internet traffic—comprising 30% of peak traffic at the time. Verizon used to deliver that traffic to its customers for free, but it now wanted to be compensated for this job, and it was asking Netflix to foot the bill.

Algorithmic preferences

There are other nuances to the flat-internet phenomenon. As video flows through increasingly vertically integrated networks, technologies that hew to the net’s principles of decentralization are getting left behind. It’s a simple function of supply and demand—video piped directly from Amazon or Netflix to a consumer ISP is simply a better experience.

Take the example of BitTorrent, once one of the major sources of the world’s internet traffic. It was a network of computers with an ingenious peer-to-peer system that allowed users to share whatever content they had—and a lot of it was video—with other users. It was going to be the future of internet video. In 2008, it accounted for a third of all internet traffic, according to Sandvine.

Things are very different on today’s flat internet. BitTorrent use has plummeted to just over 1% of internet traffic, trailing far behind YouTube, Netflix, Amazon Video and others—all backed by giant companies with the financial muscle to invest in private CDN infrastructure.

The plunge in BitTorrent traffic is emblematic of a larger shift in internet data flows. It was once thought that data would flow in a symmetric pattern on the internet: Users would upload as much data as content-creators and producers, as they would download it, as consumers. The rise of video and private CDNs means that notion has been laid to rest. “The emergence of [users] as content producers is an extremely important social, economic, and cultural phenomenon,” Cisco’s latest internet forecast report says. “But subscribers still consume far more video than they produce.”

It’s not all the tech giants’ fault, of course. BitTorrent suffered from a clunky user-experience and a proliferation of pirated material. It was useful, but pales in comparison to the slickness and speed of simply pressing play in a Netflix app.

There’s another subtle way video is reshaping the net. Video traffic inadvertently games the algorithm governing how all traffic is directed across the internet, so that video, not other types of content, are delivered in a more robust way to the user.

The algorithm is contained in the TCP protocol, one of the internet’s core technologies. There would be no internet without TCP, which allows a range of networks, each running in their own specific ways, to inter-connect with one another, creating what Vint Cerf, TCP’s co-creator, has called ”an ensemble of networks.” That required a protocol that could account for all sorts of unpredictable traffic behavior. One of the ways TCP ensures that is by having a “slow-start” phase baked into its congestion-control algorithm. That means a flow of data starts at a trickle, gradually increasing in volume. This ensures that network links don’t become congested every time a new connection is made.

It turns out that video data flows are the kind of content that takes advantage of TCP’s “slow-start” phase the best. A flow of video data has a chance to build up speed to a data-link’s top speed, whereas other kinds of content–say, clicking around on the New York Times website—are prone to interruptions. As a result, they have to constantly re-start their links to a user, meaning they experience many more ‘slow starts’ than a video link. “Getting out of the slow-start phase on an e-commerce or newspaper website is very significant,” says Dan Bowman, Sandvine’s chief technology officer. “Whereas video is not. TCP is very cautious during the slow-start phase.”

As a result, Bowman says, on any given connection, if a network had to choose between someone streaming The Grand Tour versus someone shopping in eBay, the car show would win, while the eBay shopper’s internet connection would become degraded. Alex Phillips, the WISP operator, hears dozens of stories of CDN traffic, like a big software update that’s akin to a video stream, being privileged by the network, paralyzing a user’s internet connection. “‘CDN overload’ is what we call it,” he says. “That’s where from [the CDN’s] perspective, their client is Microsoft or Apple, and they’re trying to deliver their client’s content as fast as possible. They’re employing technologies and techniques that will literally max out a customer’s connection during the time this is occurring. … In rural areas, where customers have 2.5, 10 meg connections, they are inconvenienced for a large part of the day, and as much as many days.”

What comes next

People are only getting hungrier for video, and companies are happy to feed them. New technologies like augmented and virtual reality, and ever higher video resolution mean that private CDNs will be more heavily used than ever. In 2020, two-thirds of all internet traffic will flow over CDNs, according to a Cisco forecast.

As video grows in importance, text, for so long the de facto means of internet communication, will shrink in significance. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg has already said as much, proclaiming that the future of his social network lies with video, and increasingly more immersive forms, such as virtual reality. Facebook paid $2 billion for Oculus Rift to push that process along. Facebook executives talk about the end of the written word as part of the business plan.

Facebook and Google continue to tread dangerously close to the line where they will start controlling the last-mile of internet access for their users. Facebook has several irons in the fire, including Free Basics, which gives 25 million users free or subsidized access to the internet but also restricts those users to a narrow range of accessible content. It is also working on Aquila, its plan to beam wireless internet access to people using a giant airborne drone, and it’s laying a transatlantic cable with Microsoft.

Google has its consumer ISP division, Google Fiber, which provides over 450,000 internet connections in nine cities. Like Facebook, it has a quixotic wireless internet access project, this one called Project Loon, which substitutes Facebook’s drone for a hot-air balloon. The goal is the same, to be the final link between a user and the online world.

As Big Tech gobbles up more infrastructure and accounts for more internet traffic, it poses questions for the future of the network’s openness, says Farrell, the former ICANN executive. “It means the internet is evolving from being a peer-to-peer open standards network to being a proprietary set of, effectively, VPNs [virtual private networks],” she says. “Which users are not quite aware of—they think they’re on the open internet and they’re not.”

You can imagine a future where content bandwidth demands are so great that only ISPs hooked up to content owners’ private networks can deliver the seamless experience users expect. That means if a major ISP isn’t in your town or part of the world, you might not have the benefit of that connection. That means you’re going to be left waiting as Facebook Live, or an equivalent VR stream, buffers. “It has huge implications for how the internet can grow. There are nearly 4 billion people who are not connected to the internet,” says Sastry. “How do we make it economically viable for them to connect to the internet, and have the same experiences as we have here?”

For now, internet users, infrastructure providers, and the increasingly vertically integrated tech companies are happy to keep the video streams flowing.