This post includes spoilers to the Park Avenue Armory’s Hansel & Gretel.

A throng of New York art-goers is ushered into a cavernous room. They sense they’re being watched by something too far away to see, but they don’t find any physical art to observe or touch. There are no signs that say not to take photos, so, within moments, chatter rises in the room, and people start pulling out their phones.

A new installation opening June 7 at New York’s Park Avenue Armory brings together Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Mueron. Their collaboration Hansel & Gretel, named after the Grimm fairy tale in which a brother and sister are lured into the lair of a kid-eating witch by delectable gingerbread crumbs, is an anxiety-inducing statement on selfies and surveillance.

The result of the piece’s opacity is, at first, a gentle FOMO-forward frisson: This is so cool, I am so cool, I can’t wait to show other people on Instagram how cool I am. And then slowly, surely: This is so creepy, I am so creeped out, am I already being streamed on social media somehow? (The answer is yes.)

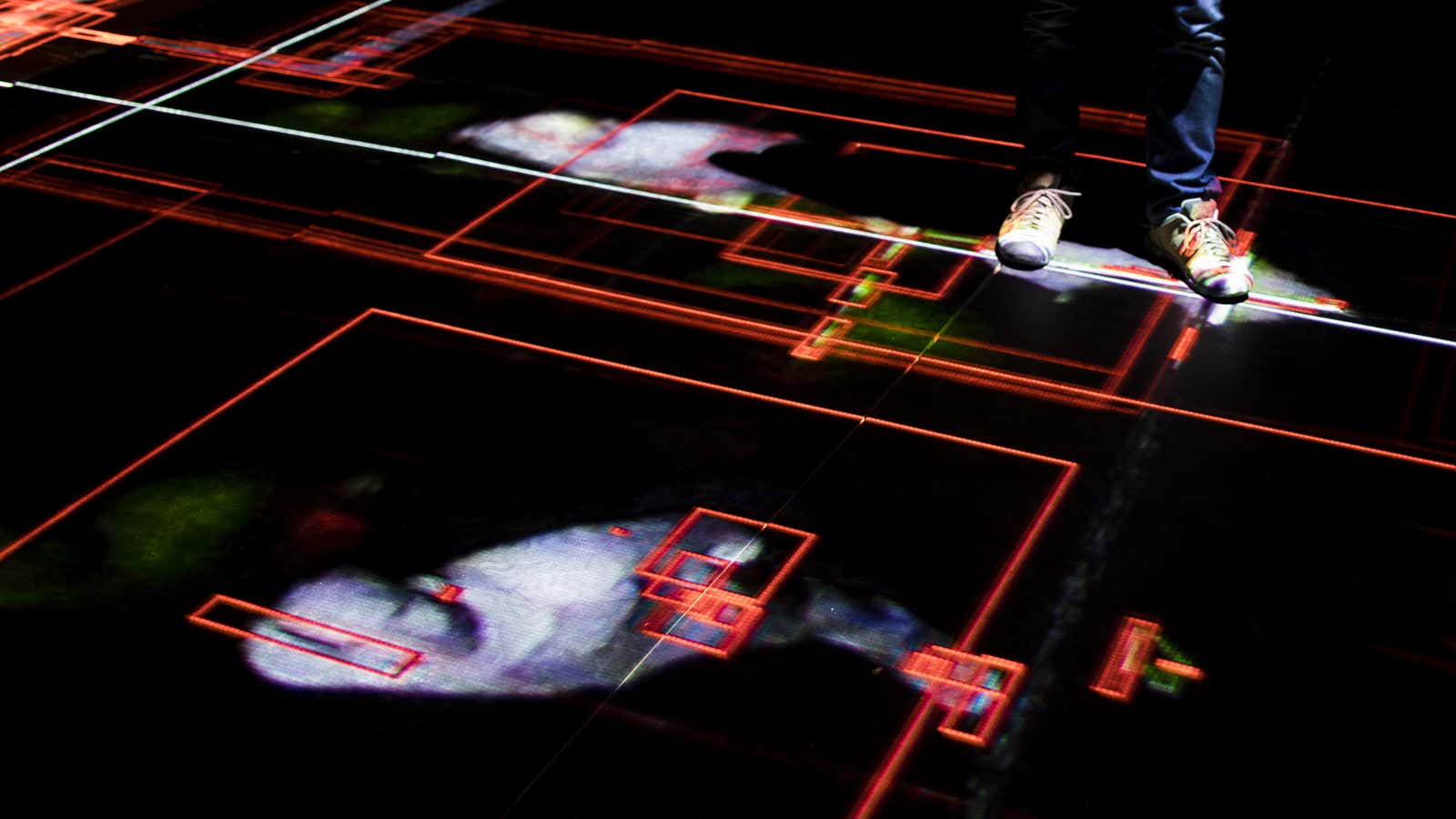

Visitors are led by a back entrance to the armory’s main space, a former drill hall. On a preview night, the vibe wasn’t a reverent, hushed build-up; it was casual, conversational. A let-your-guard-down kind of line. The single-file dark hallway erected for the piece leads to a bigger space, nearly all dark, except for a few things you can see: harshly lit rectangles projected onto the ground, red squares that follow your footsteps like the feature-extraction guides used in facial tracking software, and the faraway red and blue lights of drones.

It takes a little time to realize what’s fun about the room. Whatever unseen thing or things that capture you leave behind temporary negatives of your body in outline. As visitors realize this, the room quickly becomes an Instagrammable playground. Visitors get creative with the shapes of their bodies, leaving imprints of yoga poses, dance moves, the rock-on hand sign. People lie down and mimic snow angels, or simply look up and wait for their faces to be captured. And as they step back to observe their quickly fading shadow selves, they snap away.

The piece doesn’t make itself clear while you’re in it. You’re vaguely aware you’re being seduced by the fun, that you’re the subject of an experiment, but since you’re there anyway, you might as well get a great photo. All the while drones buzz overhead, and the room seems to blink like an enormous camera shutter.

Viewers make their way toward the exit, and are told that if they want to see ”part two,” to re-enter at the front of the building. A queue snakes its way out the main entrance, because, it turns out, people are told to stop and “look directly forward” as they re-enter.

Part two of the installation is one big peephole into part one. People huddle agog around tables of iPads, laughing and occasionally looking horrified. Flat-screen monitors show faces captured elsewhere in the exhibit, and a large projection in the center shows an aerial view of infrared-captured people scuttling around in the first room.

Oh, and there’s a literal peephole you can look through, right into the room you’ve just left.

You sit down in front of an iPad, and the program asks you to take a photo of yourself, to try to match you to a photo from its database. Some people look disappointed as they’re matched with the wrong faces: A man with glasses is clearly not the man with glasses he’s shown. It’s a weird feeling, waiting as the program searches for you. It’s scary to be ID-ed, but deep down, you want the thrill of being included.

I’m not disappointed, because they’ve found me. A 61% match, says the program. It’s 100% me, looking like a cop in a noir film who’s midway through a long, corny voiceover.

The creepiness unfolds rapidly as you click through all the options. You can watch a livestream of people entering the building, standing in the hallway, exiting part one, entering part two, people who ostensibly do not know they’re being watched. (According to the armory, all shows have photography disclaimers on the ticket.) A little YouTube icon graphic hovers in the lower right-hand corner, saying, “Oh, and everyone can watch all of this online right now.”

And you’re even more unnerved to find out that all the images and video collected from the show are being archived, potentially for Ai Weiwei’s future whims.

As you wander through, you realize what you’ve known all along: This is what life is already like in smartphone-dense cultures. People pull their phones out and document other people without their consent all the time—in the street, on the train, at school. You know, vaguely in the back of your mind, you’re being tracked by cameras you can’t see installed for security, and that Facebook can ID even a smushed version of your face without you realizing. But what are you going to do? Stop walking around? Leave all social media?

You know you look dumb when you’re posing for a selfie at a cool event. What are you going to do, not take one?

Hansel & Gretel is overtly about living in a police state, but it’s just as good as a critique of our love of documentation and display. The piece works. And not because it makes you think, hmm, I should really change my habits. But because you know you won’t. You know you’re already trapped in the culture that we have, the one in which we spy on each other, upload our findings without context, and then gawk, all together, in delighted horror.

This story was updated to reflect that all shows at the Park Avenue Armory contain photography disclaimers on their tickets.