If you envision Cairo this evening as a battleground of three reluctant armies, you have a fairly clear picture of the confrontation that is deciding the fate of Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi.

At the head of one of the armies—the civilian forces of the Muslim Brotherhood—is the 61-year-old Morsi himself, who, just a year after winning election, seems to stand little chance of surviving as Egypt’s national leader. His opponents say he behaves like a dictator, has done too little to improve the economy, and that he should therefore step down.

The streets are filled with a second army—the secular middle classes that are exasperated with Morsi. The June 30th Front, which represents a cross-section of opposition groups, today appointed Mohamed El-Baradei, the former international nuclear negotiator, as its representative in any talks with Morsi. El-Baradei previously urged Egyptians to take part in the demonstrations aimed at ousting Morsi. Yet, regardless of the advantage in size that they enjoy over the first army, the anti-Morsi demonstrators do not seem to have what it takes to actually force him out alone.

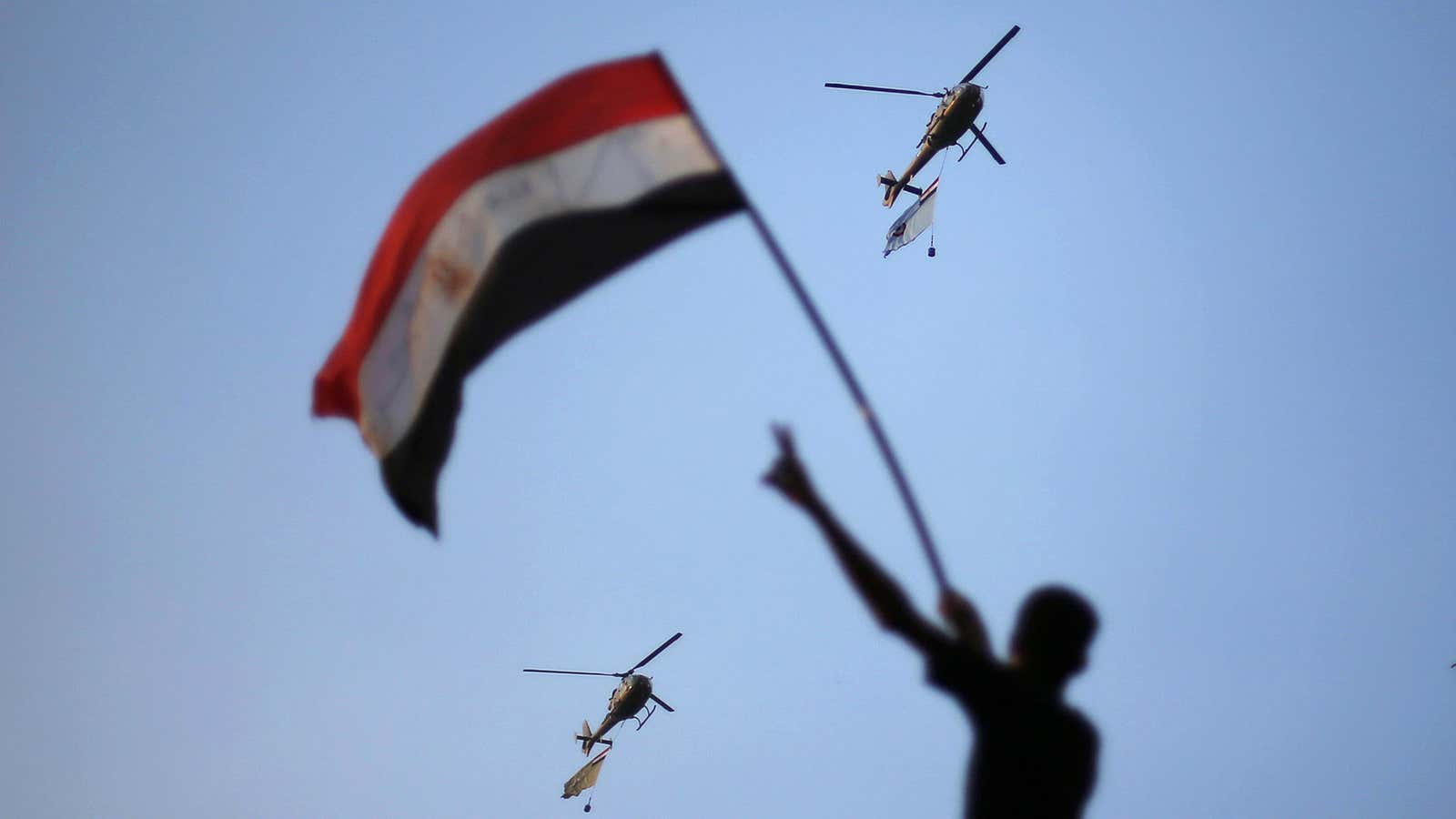

That leads to the third army—Egypt’s actual military. Led by General Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, the military at least theoretically has the means to empower either of the other two vying forces. It has delivered a 48-hour ultimatum for the president to find a modus vivendi with his opponents, or else—the not-explicit but clear threat—it will enforce its own will. In doing so, it effectively embraces the anti-Morsi forces. In a television address this evening, Morsi rejected the ultimatum. Yet the military’s forcefulness makes these seem like Morsi’s last hours or days as Egypt’s leader.

But getting there does not seem simple. The military cherishes its traditions as protector of the nation, and thus appears to be hesitant to push out Morsi in a harsh way that makes Egypt look like a banana republic. Yet, given the recalcitrance of Morsi and his opponents, the outcome seems likely to involve blunt force and at best to seriously set back the nascent democracy.

“While there is still an opportunity for a negotiated settlement, it is becoming less likely,” Hani Sabri, director of Middle East and North Africa for the Eurasia Group, wrote in a report today.

A source close to the military has briefed reporters of its plans should Morsi fail to achieve a negotiated settlement: The military will push him out, dissolve the Islamic-led Parliament, and establish a broad-based, temporary ruling council in their place ahead of an amended constitution and new presidential elections.

Is this a bluff? Regardless of their volubility, all three armies seem to want reconciliation. The problem is that they want it on their own, individual terms.