The Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, New York, is one of the most contaminated places in America, with stink and filth that emanate in all kinds of weather. The US Environmental Protection Agency declared it a Superfund site in 2010. The cleanup has been slow-going.

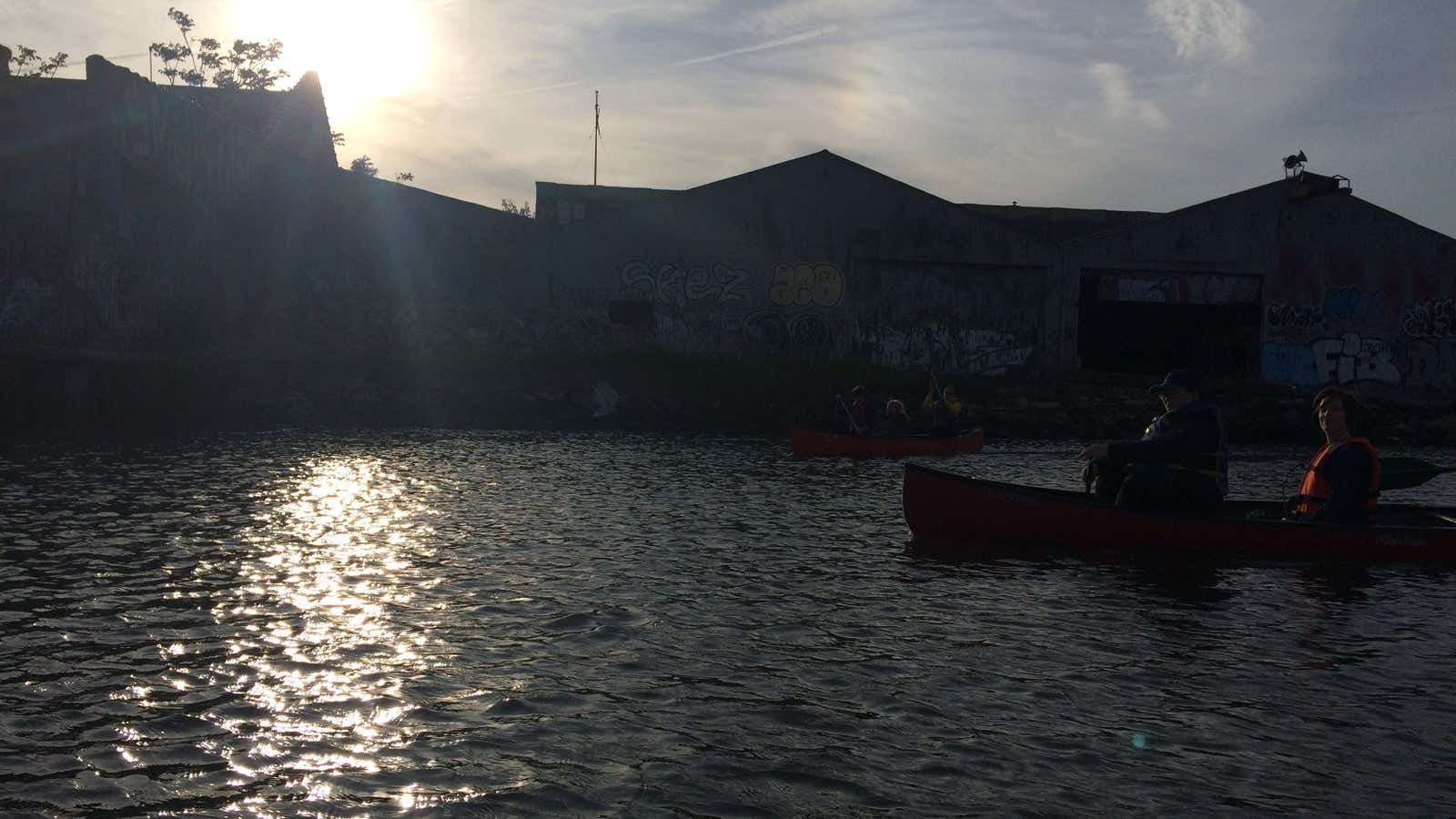

When it rains heavily in Brooklyn, sewage overflows into the waterway, and residents in nearby neighborhoods are urged not to shower or do laundry to minimize the amount of water carrying garbage through the system. On sunny days, the air is putrid and the water’s surface is slick with pollutants. Bits of litter bob along the top, floating past warehouses spray painted with graffiti—countless colorful tags accumulated over time, a message from street artists to keep Gowanus gritty.

But real estate developers are undaunted by the toxicity and aren’t reading the writing on the warehouse walls. They see dollar signs in Gowanus.

The South Brooklyn neighborhood attracted $440 million in investment over the past decade, DNA Info reported in May. A full third of Gowanus properties changed hands in that time. Among the investors is Kushner and Company, the real estate development firm owned by the family of US president Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

These bets on Gowanus could prove very lucrative, especially if the city decides to rezone the low-rise manufacturing neighborhood to allow more residences. New York mayor Bill de Blasio is considering a rezoning, which would mean big payoffs for investors who could transform warehouses and factories into tall high-rises, with apartments and condos ready to be gobbled up by a ravenous residential real-estate market.

Locals are preparing for any outcome, but are somewhat wary of development. A panel discussion in May at the Brooklyn Historical Society, titled “Gowanus’ Triple Bypass: Change Through Art, Design, and the Environment,” explored the balance between opportunity and preservation of the neighborhood’s natural yet hazardous character. According to moderator Joseph Alexiou, author of Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal, the neighborhood’s struggle to maintain its identity while growing economically is typical for the city. “Every story in New York City is a real-estate story,” he said.

Already, Gowanus has changed dramatically. The New York Times in 2009 called it a “no man’s land between two darlings of brownstone Brooklyn, Carroll Gardens, and Park Slope.” Not so anymore—as property in neighboring areas dramatically escalated in desirability and value, Gowanus inevitably became attractive to developers. And the federal government committed in 2010 to cleaning up the canal, a project that may finally start to take shape this year.

The neighborhood is still a little wild; to love Gowanus now you must love grittiness, rusted elegance, and seeing the busted insides of the city laid bare. Philip Silva, an environmental researcher and lecturer at The New School, told the panel at the Brooklyn Historical Society that one of the reasons Gowanus artists and architects have felt able to be free and creative is that the neighborhood’s many derelict buildings feel available to decoration and redesign. “The stakes are not that high, so it’s a big experimental playground,” Silva said. He’s worried that rezoning will make Gowanus too expensive for artists and erase the neighborhood’s unique flavor and creativity.

The area is also attractive to naturalists

Among the ironic delights of the toxic canal is the fact that it houses wildlife. Silva says he takes his students there to see nature and industry intertwined..

The Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club, a nonprofit that runs recreational canoe rides along the waterway and advocates for canal cleanup, lures rowers with promises of “ducks, seagulls, herons, geese, egrets, horseshoe crabs, blue crabs, fiddler crabs, baby flounder, shrimp, mussels, killifish, jellyfish, and a raccoon that has established residency near our launch site.”

For Owen Foote, club treasurer, the estuary is a passion, and its cleanup his constant pursuit. Foote is an architect, and after work one Thursday evening in May, he shows up at the canoe club launch site on the banks of the Gowanus, a few blocks from Smith Street, wearing a suit. Quickly, he exchanges the gray suit jacket for a life jacket, issues instructions, and directs me and a group of other Gowanus-curious adults to sign waivers. Then Foote leads us in launching three canoes, sharing the waterway’s troubled history as we row down the Gowanus.

Before it was a canal, Gowanus was a series of inlets that nourished Native Americans with fish. The Dutch discovered this bounty and enjoyed its natural riches until the mid-19th century. Then the inlets were connected and transformed into a 1.8-mile-long canal that became a major American maritime hub, soon to be poisoned with industrial pollutants and pumped full of raw sewage.

Nothing was done about this until the 1970s, when residents in nearby neighborhoods protested the smell of the Gowanus, more than a century after the canal was built, the city began cleaning up the bed of the Gowanus by scooping out pollutants and litter at the bottom. The dredging, the New York Times reported in 1975, has “initiated the first step of a massive pollution‐control program that will, by the 1980s, completely eliminate the discharge of raw sewage now being pumped into the canal.”

That turned out to be wishful thinking. Sewage is still pumped into the canal on rainy days when water-treatment plants overflow, Foote says, and as we row along the water with its poisonous sheen, he points out places where industrial pollutants are still dripping daily into the canal through busted pipes.

The 2010 Superfund designation promised federal funding to clean up the waterway. The site cleanup of Gowanus was finally approved by the federal government in September 2013 and plans for the cleanup are expected sometime in 2017, according to the EPA.

A local EPA contact has assured residents that the site will get the money it’s been promised and that the waters of the Gowanus will someday run clear—despite the threat of a largely diminished 2018 EPA budget proposed by the Trump administration. Our guide is skeptical. He’s spent two decades advocating for cleanup of the Gowanus and is both frustrated by the slow grind of environmental protection and wary of developers’ vision for the future of his beloved estuary. Foote points to a park on the banks of the canal built as part of the construction of a huge Whole Foods in Red Hook, Brooklyn, in 2008; it’s a bare field with a few unused picnic benches and tables. “We had hoped they’d make a railing for fallen boaters and be more creative about their use of space,” he says.

Nonetheless, Foote, like everyone eying the Gowanus right now, understands that change is coming, and that it will take cooperation between the community, corporations, and the government to clean the canal. The canoe club vows to be the voice of the water in the perpetual saga of New York real estate. Its motto, in relevant part, is as follows:

We will never bring disgrace to this, our estuary…. We will fight for the ideals and sacred things of the waterfront, both alone and with many…. We will transmit this estuary…greater, better and more beautiful than it was transmitted to us.