So the world’s most politically apathetic youth have finally found their voice. In doing so, they have forever altered British politics. The man to inspire them? An elderly politician widely derided by his opponents, the press, and most of the elected members of his party (paywall).

The Labour Party’s Jeremy Corbyn was facing a landslide defeat in the British election held last week. Prime minister Theresa May had called a snap general election in a bid to win more seats from the (mainly older) voters who backed Brexit, and was leading by 20 points in the polls at one point.

Facing that, he looked to the young—many of whom felt burned by Brexit—to back him and deny May the mandate she was seeking. This was risky—voter turnout among young people is notoriously low in the UK.

Over the last two decades, youth turnout fell from 66% in 1992 to around 40% in the 2015 general election. By contrast, Brits aged 65 have always voted in droves (turnout averages around 75%). The UK has had the largest gap in voter turnout between the old and the young in the OECD.

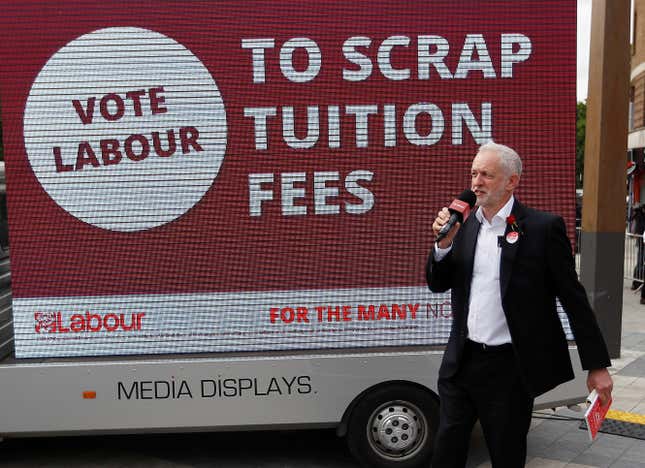

Corbyn’s bold manifesto promised to ban unpaid internships and cap rents so they would only rise with inflation. He would make universities free again—they were no tuition fees in England and Wales for higher education before 1997—and even hinted at plans to wipe out some student debt.

For campaigners on the ground, it was obvious Corbyn had tapped into the despair that many young people felt in the country. Over the last seven years, tuition fees had tripled; government grants to help the poorest attending universities were axed; under-25s lost their entitlement to housing benefits; the young were squeezed by a spiraling housing market; and job prospects have deteriorating “alarmingly,” according to Britain’s biggest trade union.

“The reception from other young people was amazing,” says Sam Gardner, who hadn’t been involved with politics until Corbyn won the leadership of the Labour Party in 2015. Gardner was campaigning in London to get young people to register to vote and found that many already had. For those who hadn’t, Gardner helped them fill out the form on their phones.

Garnder also pointed to an odd phenomenon called Grime4Corbyn—which brought together the popular British rap scene with those enthused by Corbyn’s manifesto.

“I thought this was the most important election I might experience in my lifetime,” says Becka Hudson, one of the founders of Grime4Corbyn. “There were only six weeks to make or break the NHS [the country’s underfunded universal healthcare system], schools, social care, the welfare system. The future of almost everyone I know.”

Popular grime artists, JME, Professor Green, Akala, and Novelist, called upon their largely young, urban supporters to register to vote. Those who had were promised tickets to a grime show, which brought together rappers and young voters to champion Corbyn. Many of these artists had admitted they hadn’t voted before, but called on their supporters to back Corbyn and his vision for the country.

“For young people, the biggest draw for them was the £10 minimum wage and free university education,” says Amina Gichinga, who was involved with Rize Up, a campaign to get 18- to 24-year-olds registered to vote. Gichinga saw enormous support for Corbyn as she canvassed young people on public transport and handed out leaflets.

Other campaigners took less traditional routes to shore up votes where it mattered. Charlotte Goodman, a postgraduate law student, and Yara Rodrigues Fowler, a Labour activist, created a Tinder bot to mobilize young people to vote in swing areas. “On Tinder you speak to people who are outside your own bubble,” Goodman says. Using the profiles of volunteers, the bot sent out as many as 20,000 messages to matches in swing areas over the election.

“There are some constituencies where the vote was extremely close, like Dudley North, where Labour won by 22 votes, and we will have sent hundreds of messages to people in that area,” Goodman explains.

In the end, over a million young voters aged up to 25 registered to vote in the run up to the June 8 election. More under-25s have registered to vote than at the same period in the run-up to the Brexit referendum last year and the last general election in 2015.

This higher youth turnout may have been key to denying May her expected landslide victory. May lost the Conservative majority and is now in the process of forming a minority government. Labour increased its seats by 30 and its vote share 40%—the largest share of the vote that Labour has won since 1997. The election saw the highest turnout in 25 years, with nearly 70% of Britons voting.

There’s no data yet on youth turnout, but early data shows that in areas where fewer than 7% of the population is aged 18-24, the swing to Labour was 2.5%. But in areas where at least one in 10 people were aged 18-24, there was a 5% swing to Labour in seats.

The results shocked the country. Even Gardner admits he “didn’t dream we’d do this well.” US senator Bernie Sanders, congratulated Corbyn after the results came out, saying he was “delighted to see Labour do so well.” The results left some Sanders fan at home—who are quite similar to Corbyn’s young, urban base—wondering what could have been.

Corbyn has now drawn level with Theresa May in a poll asking who would be the best prime minister (he was 39 percentage points behind a month earlier). In other polls, Labour is now ahead of the Conservatives.

“I’m so excited for the future,” Gardner says. “Next time we’re going to win. And win big.”