Women, now in their 60s, who were forced into arranged marriages during the Khmer Rouge are now seeking justice in a UN-backed court.

One of the survivors, Sa Lay Hieng, described her ordeal in court, saying, “I refused [to marry] several times, but finally the sector committee said I was a stubborn person.”

Another woman, identified only as 2-TCCP-274 to protect her identity, said she was compelled into marrying a Khmer Rouge official during a mass ceremony. When she rejected her new spouse’s advances on their wedding night, he complained to his commander who then raped her.

“I had to bite my lip and shed my tears, but I didn’t dare to make any noise, because I was afraid I would be killed,” she said. She was eventually sent back to her husband.

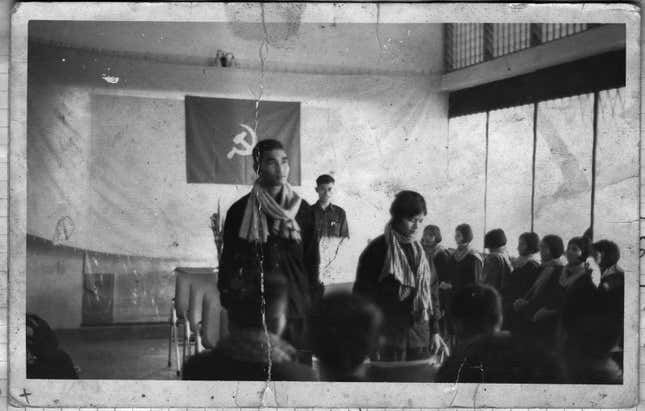

Forced marriages were held in almost every village across the country without the traditional Buddhist rituals and blessings from families and relatives. They were planned and held in a systematic way. Most couples were married off to someone whom they had never seen or met before.

One such survivor is Souk (not her real name) who was married against her will to a Khmer Rouge member she had never met. Her wedding, which occurred during a mass ceremony, lasted less than five minutes.

Souk was given instructions to enter a room and compelled to have sex with her new husband. When she refused to have sexual relations, she was raped after having a gun pointed at her by an official who demanded that she has sex with her spouse.

“He said that if he raped me and I shouted, then I would be shot dead,” she said in court.

“After that warning, after that rape, that I had to shut my mouth and had to agree to live with my newlywed husband,” she said.

Souk had to meet her husband every 10 or 15 days under the soldiers’ command who tried to ensure that the couple consummated their marriage.

These shocking testimonies were revealed for the first time in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), which was jointly set up by the Cambodian government and the United Nations (UN) in 2006 to prosecute the most senior members for crimes committed during the brutal regime. The court is the only legal apparatus that can try and indict those held accountable. Many of the senior leaders of the regime have being charged in recent years. Prosecutors have filed a request to sentence Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan for crimes against humanity in Case 002/02.

For years, the tribunal had overlooked the crime of forced marriages amid mass killings and other forms of human rights violations. It was only in August 2016 that the tribunal first heard cases of forced marriages. The proceedings were completed by mid-October and a provisional judgment may be delivered in late 2017.

Forced marriages were used as a dominant tool by the Khmer Rouge regime to increase the next generation of workers for labor power. They were partly designed to double the population size to 20 million within a decade. Such a practice was a pervasively instituted policy where couples were arbitrarily married against their consent and forced to maintain marital relations. Those who refused to have sex were punished with violence. For women the punishment for refusing to consummate was usually rape.

Until today, it is uncertain how many men and women were victims of forced marriages. Public prosecutors have estimated that the number may be around several hundred thousand people.

Forced pregnancies

Human rights lawyers and activists have expressed concern that the UN-backed court is not investigating forced pregnancies separately from forced marriages. Women like Souk are not only victims of forced marriages but also of forced pregnancies. Forced pregnancies were given recognition as a separate international crime in the Rome Statute of the International Court of 1998.

Theresa de Langis, a writer and international consultant for women in conflict and post-conflict scenarios, wrote that “at least one small study of victims of forced marriages indicates that over half of these marriages resulted in one or more children, and testimony has already been heard as to the severe impacts on women’s health and psyche as a result of this added, almost unimaginable burden in a time of mass starvation, slave labor, and epidemic levels of illness.”

She referred to a report published by the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO), a Cambodian non-profit organization that provides mental health care and psychosocial support, which stated that especially female survivors continue to suffer from gynecological and physical issues. This has taken multiple forms such as depression, anxiety, panic attacks, insomnia, and flashbacks. Many suffer from psychological problems related to trauma. The findings of the report were based on interviews conducted with 222 respondents who were all civil complainants to the ECCC.

Argentine human rights lawyer María Lobato raised the same issue in her report titled “Forced Pregnancy During The Khmer Rouge Regime” that survivors of forced pregnancy suffered both physical and psychological harm. Many women were denied access to healthcare and had to return to labor work right after giving birth.

“The suffering endured by victims of forced pregnancy can only be adequately represented through the application of a specific legal category,” Lobato wrote in her report.

The country’s conservative values have led many couples of forced marriages to continue living together. Divorce is a taboo in Cambodia and the incidence of divorce remains low. For similar reasons, the remaining survivors have not mustered courage to share their personal story.

Hoy Vathana, a mental health counsellor from Cambodia, has given her opinion on how to tackle this problem. “Many women need to be empowered enough to speak up so that their voice, their needs, and their rights are heard. It is a long process to advocate for public acknowledgement (of the forced marriages) and in terms of compensation,” she says.