In 1814, David Brewster had an epiphany: light + casing + mirrors + things to reflect = the most fun ever?

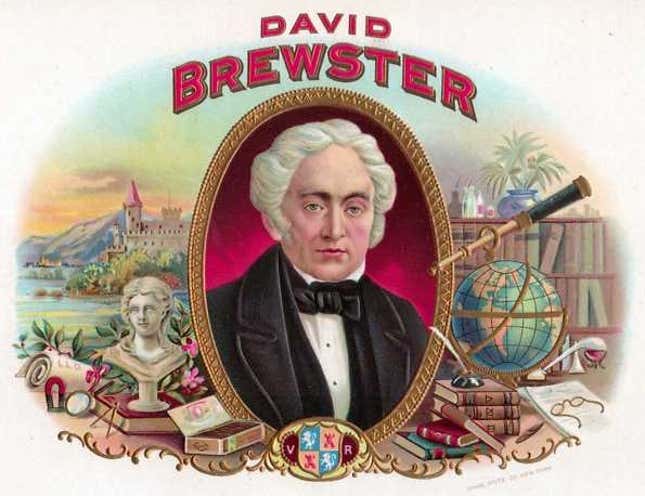

The Scottish scientist—already esteemed for his work in optics—named his invention the kaleidoscope, combining the Greek words kalos (beautiful), eidos (form), and skopeō (to see). He spent two years developing a prototype, and on August 27, 1817, arrived at Stobo Castle in Peebleshire, Scotland, to sign the official patent.

“Any object, however ugly or irregular,” Brewster wrote in the filing, “[when] placed before the aperture…. will coalesce into a form mathematically symmetrical and highly pleasing to the eye.” (Some 150 years later, “first lady of kaleidoscopes” Cozy Baker would demonstrate this point by aiming a teleidoscope—a kaleidoscope with a clear lens on the end—at a plate covered in egg yolks and cigarette ashes. “It came out beautifully,” she declared.)

Humans have long been fascinated by reflective symmetry. Legend has it that ancient Egyptians created pseudo-mirrors out of polished limestone slabs, so that people could dance in the resulting patterns of light. But the story of the kaleidoscope, patented 200 years ago, has all the makings of a Silicon Valley spinoff. There’s an eccentric founder, a breakthrough idea, and a case of IP theft. A once-viral hit struggles to iterate. An influencer saves the day. And at the center of it all, a handheld source of endless visual entertainment.

Kaleidoscopes may not be able to text, tweet, or hail a horse and buggy, but they were unputdownable in their day—and an analog omen of the mobile mania to come.

Smoke and mirrors

Brewster was convinced his invention would be a hit. “It would be an endless task to point out the various purposes in the ornamental arts to which the kaleidoscope is applicable,” he wrote. “It may be sufficient to state that it will be of great use for architects, ornamental painters, plasterers, jewelers, carvers and gliders, cabinet makers, wire workers, bookbinders, calico printers, carpet manufacturers, manufacturers of pottery, and every other profession in which ornamental patterns are required.” (He would have killed on Shark Tank.)

Brewster’s confidence wasn’t misplaced, but his faith in Britain’s early-19th-century patent system was. “People were ripping it off before he’d even gotten the patent through the door,” says Dawn Correia, a kaleidoscope historian and associate lecturer at the Open University.

“[Brewster] wasn’t a maker, so he had to approach different people about his idea,” she says. “Somebody—it’s never been proven who—either let it slip or heard the idea and thought, ‘I could do something similar.’”

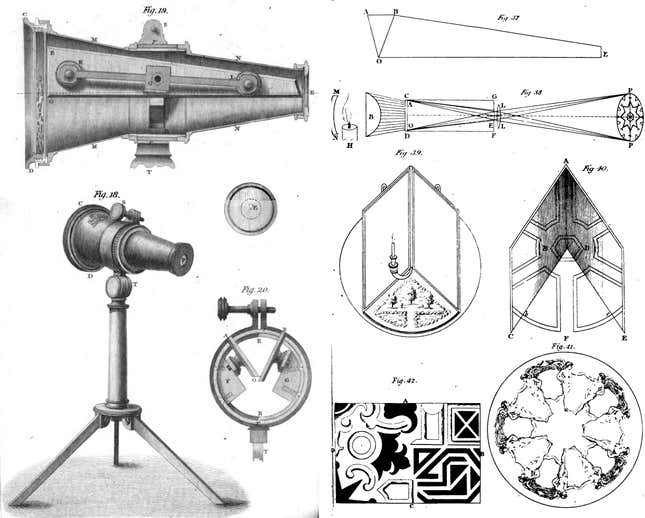

Unfortunately for Brewster, kaleidoscopes are pretty easy to build. Your basic scope is made up of at least two mirrors, placed at an angle and enclosed in a tube. One end-piece is usually opaque, and a case known as the “object cell” or “object case” is placed in front of it. The cell can hold anything—beads, gems, seashells, liquid, Sea Monkeys—and its contents are reflected and multiplied in the scope’s mirrors to produce a symmetrical circular pattern known as a mandala, which is visible through the eyepiece on the other end. While the outside of a Brewster kaleidoscope was usually made of wood, a quick-and-dirty version can be constructed with something as low-frills as the cardboard core of a toilet paper roll.

Brewster’s patent fail is still a running joke in the kaleidoscope community. During a gala at the 1994 convention of the Brewster Kaleidoscope Society (BKS), scope artist Judith Paul hired an actor to dress as the organization’s namesake. He took the stage to bagpipe music and a smoke machine before declaring to the audience: “I wish I’d gotten a better patent!”

The real Brewster, however, took it hard. “Both [Sir Joseph Banks and Sir Everard Home] assured me that had I managed my patent rightly, I would have made one hundred thousand pounds by it!” he wrote in a letter to his wife in 1818. “This is the universal opinion, and therefore the mortification is very great. You can form no conception of the effect which the instrument excited in London; all that you have heard falls infinitely short of the reality. No book and no instrument in the memory of man ever produced such a singular effect.”

Brewster may come across like a self-aggrandizing hype man, but Correia cites that letter in a piece she wrote for the Scientific Instrument Society’s quarterly bulletin last year, which argues—among other points—that comparisons can be made between the kaleidoscope’s early popularity and Nintendo’s 2016 hit, Pokemon Go:

“The kaleidoscope at its inception also invoked a craze, with prints and newspaper articles describing it as a ‘mania’ the like of which had never been seen before. As a portable device, it was visual entertainment that could be engaged with on streets, in parks, marketplaces and backyards as a pastime, and provide a contrast to the harsh realities of the changing times and hardships brought about by industrialization.”

Despite being a played patent-holder, Brewster couldn’t help but keep singing scopes’ praises. In 1819, he published A Treatise on the Kaleidoscope, which reads like a technical guide crossed with a love letter: “Those who have been in the habit of using a correct Kaleidoscope… will have no hesitation in admitting that this instrument realizes, in the fullest manner, the formerly chimerical idea of an ocular harpsichord,” he wrote. In other words, it was music for the eyes.

Penny for a peek

By 1820, knockoff scopes had flooded England, and the public was obsessed. Writes Correia: “Newspaper articles recounted incidents of fights breaking out between sellers, poems were attributed to it, debates ensued as to the originality of its invention, and calculations were made as to the probability of repeating any pattern.”

One newspaper article complained of boys walking into walls while looking through kaleidoscopes; another kvetched about scope users running into cyclists on the street. (The draisienne, or “dandy horse,” a pedal-free precursor to the modern bicycle, had recently been introduced.) Large kaleidoscopes were set up on street corners, where passersby could pay a penny for a peek, and parlor scopes became the must-have accessory for the middle and upper classes.

Brewster’s hit left him none the richer, but did give him notoriety. He was honored by several countries’ royal academies, and knighted by William IV in 1832. Brewster also continued his experiments, discovering physical laws of light polarization and metallic reflection, as well as the optical properties of crystals. He invented the binocular camera, the polyzonal lens (a precursor to the modern lighthouse lens), and two types of polarimeters, and also wrote two biographies of Isaac Newton.

“He has indeed some minor specialties about him,” Scottish poet and essayist James Hogg wrote of Brewster in 1832. “For example, he holds that soda water is wholesomer drink than bottled beer, objects to a body’s putting a nipper of spirits in their tea, and maintains that you ought to shave every morning, and wash your feet every night—but who would wish to be severe on the eccentricities of a genius?”

By the mid-19th century, kaleidoscopes had taken off in America too, in large part thanks to Charles G. Bush, who immigrated from Prussia in 1847 and came to scopes from rope-making and microscopy. Bush’s scopes were sturdy, and meant for parlor display. Most featured a barrel of black or brown hardboard, topped with a spoked brass wheel that rotated an object case containing a liquid-filled ampule.

Between 1873 and 1875, Bush was awarded patents for several kaleidoscope improvements, mostly having to do with adjustments to the object case. He also developed an easy-to-disassemble scope stand for transport, making the kaleidoscope also the Nintendo Switch of its day. Bush built thousands of kaleidoscopes from his homes in New Hampshire and Vermont before his death in 1900.

Renaissance mandala

This is where the story of kaleidoscopes might have ended—an optical instrument gets popular, then passé, and soon all that remains are cheap versions for kids. By the middle of the 20th century, the best place to find a scope was at a five-and-dime store, and advances in radio and television were sending even those sales into a downward spiral.

“There are a lot of people that just think of them as a toy,” says Jean Schilling, co-owner of Iowa-based scope seller Kaleidoscopes To You. “It’s been hard to disprove that for people, and build that value, that this is an art form.”

Kaleidoscopes to You has been in business for 35 years, and Jean’s husband and co-owner Karl has been making scopes for just as long. The company has shipped to six of the seven continents (sorry, Antarctica), and does most of its business online; Jean says they sell between 5,000 and 9,000 scopes a year. Their greatest hits include party favors for Yoko Ono’s 79th birthday, and scopes for a gift basket that George W. Bush gave to White House staffers (the interior image was of the Bush family pets).

Jean and Karl are also members of the BKS. In addition to the society’s annual convention, this group of vendors, artists, and collectors swap stories and techniques, and buy each other’s work. This year’s conference—#27—gathered 250 attendees for three days in Kyoto. (Japan has many scope enthusiasts.)

“The kaleidoscope family is just that,” says Charles Karadimos, one of BKS’ founding artists. He has been making scopes for nearly 40 years, and was one of the most influential artists of the Kaleidoscope Renaissance: a resurgence that kicked off in the US in the late 1970s. Some of that interest had to do with the rise of a craft and folk-art movement that drew attention to beautiful handmade objects. But anyone in the scope community will tell you it was mostly thanks to Cozy Baker.

“A surprise party for the eyes”

Cozy Baker, née Hazel Cozette Oliver, was born on November 14, 1923, in Wilmore, Kentucky. She married at 20, and had three children over the next 15 years. Independently wealthy, Baker was a stay-at-home mom and a frequent volunteer.

In 1981, tragedy struck. Baker’s youngest son, a 23-year-old artist named Randall, was killed by a drunk driver. Baker was devastated, and started writing to cope with her grief. A year later, she published Love Beyond Life: Six Enlightening Ways to Triumph Over Tragedy. “If you view each experience, good or bad, as an adventure and pursue new and varied interests, you will automatically feel enthusiastic,” she wrote in the book. “So turn up the wick of your initiative. It is never too late to ignite a spark of originality and kindle a new activity.”

While on book tour, Baker stopped at a craft store in Nashville, and was drawn to a kaleidoscope on display. She peered inside and was immediately hooked. “I wasn’t a career person,” she told The Washington Post in 1989. “I was a volunteer and a mother. Then suddenly I found scopes.”

It would be difficult to overstate the impact Baker went on to have in her newfound passion. Between 1985 and 2002, she wrote seven books about kaleidoscopes. She also curated the world’s first kaleidoscope exhibition, and founded the BKS in 1986. She has been called the authority on kaleidoscopes, the guiding force behind the kaleidoscope movement, ambassador of the Kaleidoworld, first lady of kaleidoscopes, kaleidoscope queen, doyenne of kaleidoscopes, patron saint of kaleidoscopes, and—her favorite—mother of the Kaleidoscope Renaissance.

“Cozy was essentially a 17th, 18th-century patron of the arts,” says Paul. “She spent her life putting kaleidoscope artists and galleries together so they would know each other and encourage each other.”

When Baker died of ovarian cancer in 2010, she owned more than 1,000 scopes. She had one made from sharkskin and alabaster, another carved from an elephant’s tusk, a $12,000 electric kaleidoscope, and one in the shape of the Chrysler Building. Her backyard featured a “kaleidopool” with fiber-optic underwater lights, and she had a “kaleidoquarium” fish tank (unstocked). In her home, scopes could be found everywhere from the dining room table to the Jacuzzi.

“I like to have [kaleidoscopes] where people are sitting or eating,” she told the Washington City Paper in 2002. “They’re nourishment for the soul.”

Baker described kaleidoscopes as combining the majesty of stained-glass windows, rainbows, sunrises, sunsets, and fireworks, and once called them “a surprise party for the eyes.” She also donated hundreds of scopes to the Salvation Army, to troops in Desert Storm, and to charities for children with AIDS.

“She was the maven—you know that Malcolm Gladwell term,” says Schilling. “She was our maven.”

She’s referring to a term Gladwell used in his 2002 bestseller, The Tipping Point. “Mavens have the knowledge and the social skills to start word-of-mouth epidemics,” he wrote. “What sets Mavens apart, though, is not so much what they know but how they pass it along. The fact that Mavens want to help, for no other reason than because they like to help, turns out to be an awfully effective way of getting someone’s attention.”

Glass to glass

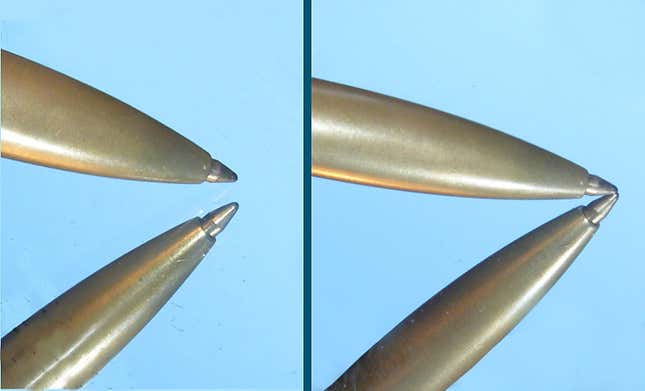

While the principles behind kaleidoscope construction haven’t changed since the 19th century, some technical innovations have led to improvements. Optical lenses, used in eyepieces, are more precise, available, and affordable now than when Brewster or Bush were making scopes. Even more important, advances in the front-surface mirror, developed for things like cameras and photocopiers, have dramatically improved mandalas’ symmetry, clarity, and intensity of color.

“The normal mirror in your home has silvering on the back of a piece of glass,” explains Paul. “For the mirror that is used in good-quality contemporary kaleidoscopes, the silvering is on the front of the glass. So when you take two pieces and put them together, you have silver coming to silver. You don’t have the interruption of glass coming to glass. The first-surface mirror is crucial to a great kaleidoscope.”

The Kaleidoscope Renaissance also attracted a new wave of artists; contemporary scope-makers come from glasswork, woodwork, metalwork, jewelry-making, and beyond. Their aesthetics vary wildly.

Paul, an art conservator, and her husband have made thousands of kaleidoscopes, and own 450. Her scopes are usually themed—the interior images match the exterior—and designed to be durable. “An art conservator thinks long-term,” she says. “[So] I use only things that, as far as I know, are permanent and immutable.” The bodies are made of powder-coated aluminum, and one type is wrapped in sign-makers’ vinyl. Paul’s object cells are usually filled with mineral oil, and hold anything from crystals to bits of metal.

Karadimos makes his scopes exclusively with glass, each piece of which he selects and molds by hand. He has collaborated with Harry Winston on gold and diamond kaleidoscopes, designed the world’s largest kaleidoscope in upstate New York, and partnered with a renowned ceramics artist to make scopes in Japan. If Paul’s scopes seem perfect for a sunroom, Karadimos’ feel suited for a study, where their fragile beauty can be kept out of reach of dogs and boisterous children.

Scopes have also maintained a quiet presence in the art and tech worlds. In 2009, the American Folk Art Museum hosted an exhibit of quilts by Paula Nadelstern, who uses patchwork techniques to create mandalas (she owns more than 100 scopes). In 2011, Judith Paul became the basis for a kaleidoscope-artist character in Spirit Bound, a novel by bestselling author Christine Feehan. And just this month, Apple announced a kaleidoscope face for the newest iteration of its Apple Watch.

Kaleidotherapy

Feehan and Paul have known each other for eight years—Paul goes to some of Feehan’s conventions, and Feehan granted Paul’s wish to name the Spirit Bound love interest after her husband (in a book of Russian dudes, he is the lone Thomas Vincent). But Feehan came to kaleidoscopes on her own.

“One of my grandchildren is autistic, and I noticed that when she was really upset, one of the things I could do to calm her down was let her look into this one kaleidoscope,” she says. “She would stop getting upset, and I became interested in the other uses for kaleidoscopes.”

As healing goes, kaleidoscopes live in the same territory as color therapy: medically dubious, but tantalizing. There is something meditative about looking through one: It’s quiet, immersive, and individual. Correia likens it to watching a washing machine. The symmetrical patterns appeal to a base human craving for balance, and mandalas are a spiritual symbol in Hinduism and Buddhism. Baker wrote that kaleidoscopes paired well with a period of daily reflection (heh).

Perhaps it is this offer of serenity—in a 21st-century culture obsessed with mental relief—that will give scopes renewed relevance as they turn 200. “The kaleidoscope takes a controlled section of chaos; the mirror system converts it into patterns, and the human mind loves patterns,” says Paul. “The right brain wants beauty and art; the left brain wants order. The kaleidoscope is science and art, both.”