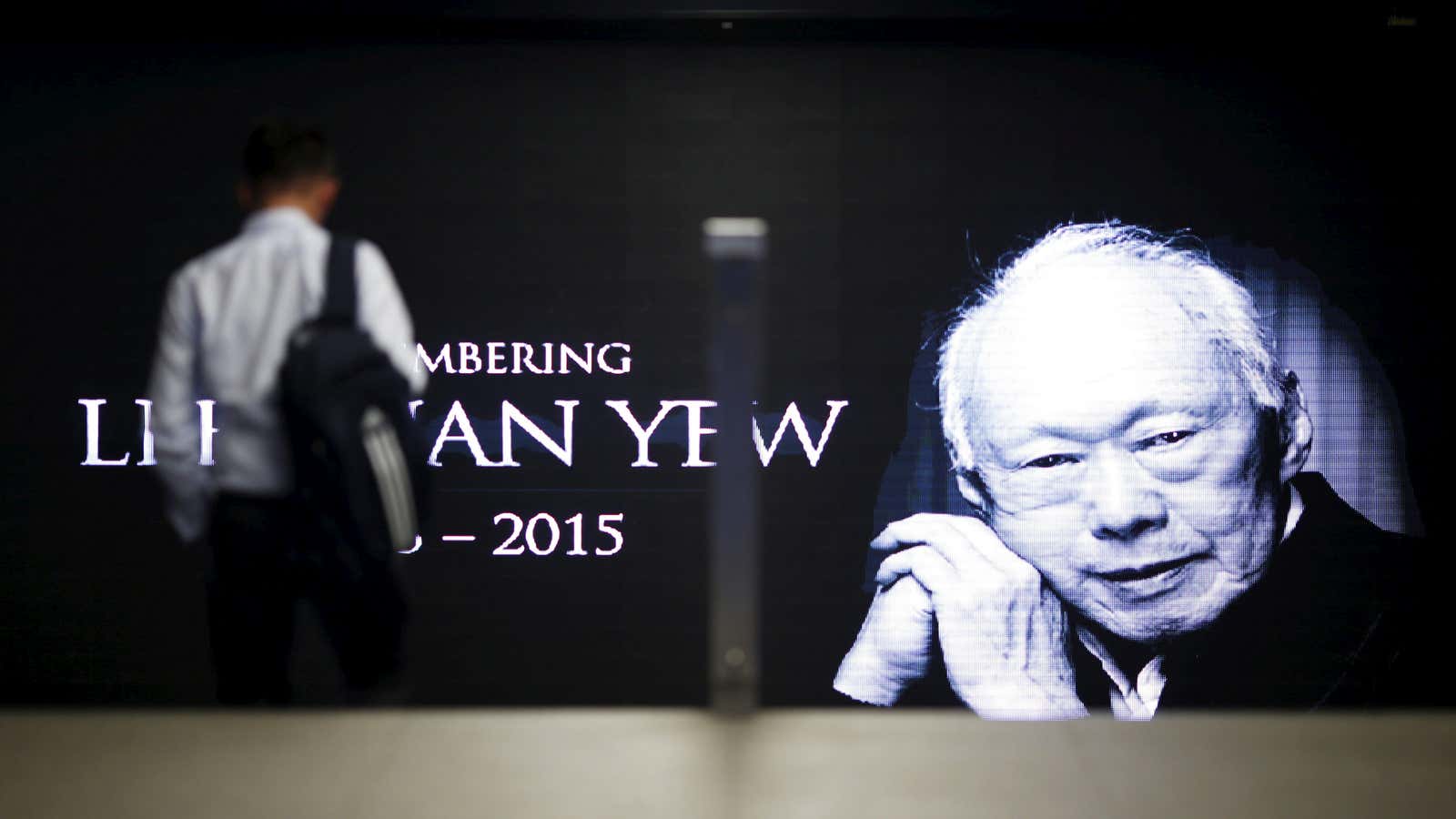

Singapore’s tightly-knit elite political circles have resorted to social media trolling, in a desperate search for a public space to vent. The two younger children of Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, have been trading blows with their elder brother, current prime minister Lee Hsien Loong, all weekend. The dispute is over the fate of the Lee patriarch’s bungalow, and whether it should be demolished in accordance with Lee Kuan Yew’s wishes, or preserved for historical value. Various cabinet ministers and Lee descendants have joined the fray. And it’s all happening on Facebook, thanks in part to Singapore’s tightly policed press.

Singapore ranks high on wealth and other development metrics, but it’s among the most repressive regimes in the world when it comes to free speech, (ranking 151 out of 180 in Reporters Without Borders’ annual press freedom ranking, and receiving 41 out of 100 points from Freedom House). Among the methods used to control the local press: censorship of films, broadcast media, and newspapers; laws that require websites to obtain licenses from the government; and a raft of rules that allow the state to appoint directors to the board of the country’s national newspaper publisher, and give a broad interpretation of sedition, secrecy, and defamation laws, according to Freedom House.

Lee Hsien Yang, the youngest child, alluded to this in an interview with the South China Morning Post on Monday: “A few of the attacks that we have had to face in private are now public—false accusations, character assassinations, the entire machinery of the Singapore press thrown against us.” His son, Li Shengwu, was even more explicit, replying to a commenter on his Facebook post who asked why the matter wasn’t in the local news yet: “Because the Singapore news is heavily controlled by the government. I’m in a position to know.” Then there’s Lee Wei Ling, the prime minister’s sister, who ended her long-running column in the national daily the Straits Times last April because, she claimed, of censorship imposed by her editors. “I will no longer write for SPH (Singapore Press Holdings, the Straits Times’ publisher) because the editors there don’t allow me freedom of speech.”

Which leads us to Facebook. The Lee siblings appear to be using social media strategically to get their message out, since local media can’t be trusted. The SCMP quoted one anonymous longtime observer of Singapore politics who likened the younger Lees’ use of social media to “guerilla communication tactics:” “[They] reflect the actions of actors who are in a less advantaged position relative to the party they are facing [off] with,” the observer said.

That the Lees are turning to social media in the face of free speech restrictions in the official press is thick with irony. Those restrictions were largely engineered by Lee Kuan Yew himself, who enacted the raft of laws that today make up Singapore’s unique model of press control, which imposes restrictions subtly, as the Singaporean academic Cherian George has observed. Rather than overtly forcing the press to spout propaganda like the Chinese, George writes, Singapore’s government uses laws that govern secrecy, defamation, and internal security, as well as partial government control over media companies, to drive self-censorship. This creates a de-facto “Western professional model” of neutrality, but in a “twisted form,” he has written.

Whatever control the Lee siblings have been subjected to, it appears to be far from punitive compared to the measures meted out to ordinary Singaporeans, who have been sued into bankruptcy for saying less about the prime minister. Lee Hsien Loong is now seeking a new forum to conduct the debate. He announced yesterday that he will answer questions about the issue in parliament on July 3.

Correction: An earlier version of this post said Lee Hsien Yang is Lee Kuan Yew’s middle child; he is the youngest.