Sprinkles, a chain of bakeries, has installed 15 or so cupcake ATMs around the US. Beyond providing on-demand desserts at any time of day or night, these machines also hold a valuable lesson for workers who fear that robots will take their jobs.

The lesson: don’t become a cupcake seller.

Prestige Economics founder Jason Schenker thinks “kioskification” and related trends in the service industry are just getting started. In the cupcake world, that means the baker should focus solely on making the cakes. The ATM, meanwhile, handles the simple, repetitive task of selling them, freeing up bakers to focus on developing new flavors or other high-value tasks.

An ATM, kiosk, or some other delivery system can increase sales, because it attracts customers frustrated by long lines or who want a cupcake during non-business hours. (Or, they are intrigued by the novelty of it.) If sales go up, then more workers are needed to make products to fill the machines—ideally, the sort of work that’s more meaningful to them than exchanging money for cupcakes. Schenker suggests that, in this way, kiosks could help create more jobs.

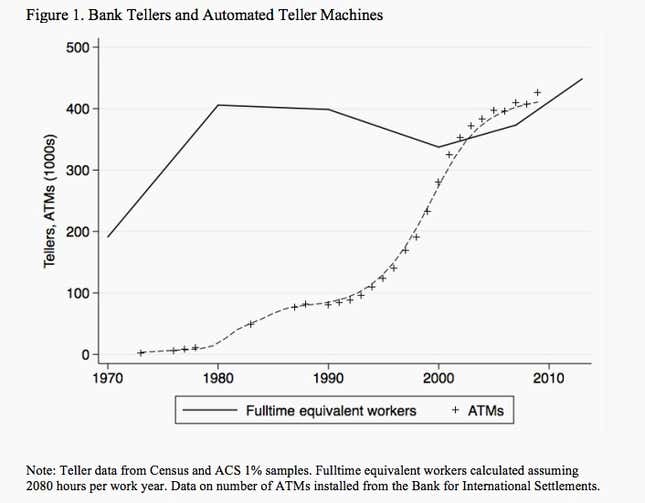

As it happens, that’s generally what happened with cash ATMs since they were invented 50 years ago. Since 2000, the number of bank tellers in the US has increased by 2% per year, faster than the rest of the labor market, according to research by James Bessen (pdf), an economist at the Boston University School of Law.

ATMs let banks operate branches at lower costs, which allowed lenders to open more of them. Therefore, “automation itself sometimes brings growing employment to occupations,” according to Bessen.

The same could be true in other industries, like the robo-advisors that are capturing a small but growing share of the financial advice business. Schenker points out that many industries make the bulk of their profit from 20% of their customers—the so-called 80/20 rule. Automation could allow financial firms to focus the efforts of human employees on personalized services for clients who have more complicated, lucrative needs.

Not everyone is convinced. The notion that automation could permanently reduce the need for human employment is a reason some think universal basic income will become necessary. French leftwing presidential candidate Benoît Hamon suggested taxing wealth created by robots and providing citizens with monthly income payments. Microsoft founder Bill Gates thinks a robot tax could be used to fund public services and training programs.

These days, if bank-teller jobs are under threat, arguably its not because of the ATM but rather the iPhone. Smartphones are streamlining a wide range of banking services, and more transactions are now made without cash. Since peaking in 2009, the number of bank branches in the US has started to decline (pdf), reducing jobs for tellers as well (paywall).

The ATM itself has also been forced to evolve, offering more features, like accepting cash deposits and integrating into our digital lives by connecting with mobile phones, according to Accenture’s Jeremy Light. He argues that ATMs will become even more important as bank branches close down. Humans, meanwhile, will focus on roles that provide more complex services, like advice.

It’s hard to predict which jobs—if any—will be created as a result of robots, apps, and other forms of automation. But as Schenker’s cupcake theory suggests, innovation doesn’t always destroy jobs, even in the industry it’s transforming.