Teaching kids coding is all the rage, with coding clubs and coding camps cropping up like Silicon Valley startups. Countries like the UK have made it part of the national curriculum, recognizing that computational thinking will be as important as literacy and numeracy for the jobs kids will have 20 years from now (or, now).

But how early should kids start to code? Many of us want our three and four-year-olds mucking it up in the backyard, not programming html in diapers.

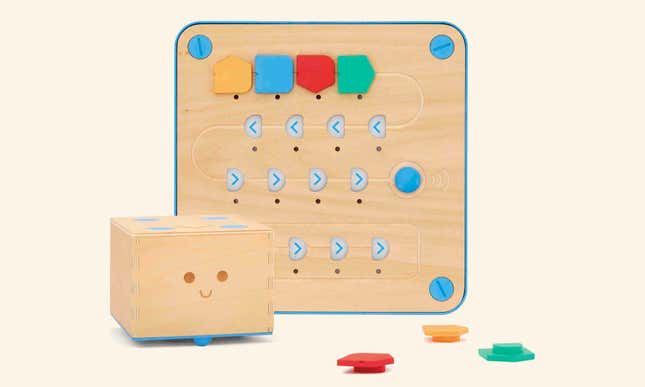

Cubetto, an insanely expensive but alluring low-tech toy, offers a screen-free, wi-fi-less option. It’s a playset that lets kids unpack the basics of computational thinking with a beautiful wooden code board, colorful block pegs, and a rolling cube robot (“Cubetto”), which kids navigate around colorful play mats of things like ancient Egypt, the ocean, or space. There’s a old-fashioned storybook element wrapped in, too.

The way it works is simple: Each block placed on the board represents a command in a simple programming language, such as right (red peg), forward (green for go), or left (yellow–there are no colors that start with “l” –at least not ones that three-year-olds know about). By placing the pegs on the code board, kids program the cute cube to move around the map (though it is of course free to go where it likes). Kids can put him on a continuous loop, or create funny patterns. There are 120 lesson plans for educators, and instructions for the less-programming savvy among us.

“We introduce tech in a screen-free, age appropriate way,” says Filippo Yacob, the 30-year-old co-founder and CEO of Primo Toys, the Italian company that produces it.

Cubetto has many virtues: It’s gender neutral—it started as a car but quickly morphed into a smiling cube on wheels—and can be used before kids can read, or write. Since there is no language, it is as useable in India as it is in Japan and Atlanta.

The drawback is its stratospheric price tag, retailing for $225 (or less, as part of a new Kickstarter campaign).

In calendar year 2016 the company grew just shy of 1800%, growing sales to $4 million worth of products to more than 100 countries, including Maryland public libraries, the Austin and Chicago public school systems and the French and Italian governments. Currently 70% of sales are from the US, and 75% of the customers are male (Yacob says these are fathers who want their children to learn to code).

Necessity is the mother of invention

In 2013, Yacob, a serial entrepreneur who’d yet to find his groove, found out he was going to be a dad. He teamed up with Matteo Loglio, an interaction designer—who now works at Google Creative Lab—and raised $56,000 in a Kickstarter campaign. They built a robot. The product was bespoke, aimed for older kids, and parents had to assemble it.

“What we learned was that there were millions of parents who did not want to build their own toy – they wanted the experience out of the box,” Yacob says.

They also realized to be successful, they had to build something that could be mass produced, and could engage young children while not scaring parents who are wary of exposing their toddler to too much tech. Simplicity would be key.

In 2015 Primo Toys got a break: Accelerator PCH Highway 1 took it on board and Randi Zuckerberg, Mark Zuckerberg’s sister, got interested and invested.

As the product took shape, Primo turned to Kickstarter again, aiming in 2016 to raise $100,000 in a month. It raised that in the first 17 hours and eventually pre-sold $1.6 million worth of Cubettos to customers in more than 96 countries. The product shipped in the autumn of 2016 (significantly behind schedule).

The design combines Montessori principles such as being child-centered and hands-on with Logo Turtle, a simple language developed in the1980s. The developers removed the idea of a screen and keyboard and replaced it with the pegs and the wooden board.

“Removing text and the language from the experience and making it completely tangible means it can be played exactly the same where no matter what language you speak” Yacob points out.

The company’s new Kickstarter campaign is now building out content via more maps and activities, which Yacob equates to levels on a video game: After emerging from one set of adventures and activities (the ocean) you can enter another (Swarmy swamp or a polar expedition). Each map comes with activity books, and is meant to expand the experience, perhaps addressing a criticism lodged at it by Wired: that it can get repetitive.

But do three-year-olds need to code?

There are plenty of skeptics who claim the coding craze has gone overboard. “We don’t need everyone to code–we need everyone to think,” writes Chase Felker in Slate, “And unfortunately, it is very easy to code without thinking.”

Count me among the moms who are all for IRL learning. But I also know coding scares me and programming feels like it is something done by another species, something I could never begin to understand. These are not qualities I hope to pass on to my daughters.

If Cubetto introduces computational thinking—do x, and y happens— and it does it in a way that does not involve a screen, it feels like a useful addition to the millions of educational toys which are neither educational nor aesthetically pleasing. After all, I teach my kids to read not expecting them to become novelists (though I would be delighted if they chose to become novelists). I can introduce them to coding in a gentle way without pushing them to become programmers.

That leaves the issue of price, which is still a major obstacle for most people. Yacob says the toy has longevity and adaptability, but that won’t make it more affordable to those who can’t shell out $200 for a toy (regardless of its educational promise).

Three are many statistics out there about how many jobs will be automated or obsolete by the time our children are grown. Yacob cites this one: 65% of the jobs our kids will have not yet been invented. It is a foregone conclusion that tech will be part of this.

But tech at three?

Here, Yacob gets philosophical. “If I look at the things that make us human—it’s our ability to ask why we are here and answer it with endless creativity. Today that is done with tech. Understanding tech allows us to be a little bit more human in the 21st century.”

It’s never too early to start being human.