Questions about whether the US president is too powerful have been raised regularly from America’s very first days to Barack Obama’s last year in office. A country created to throw off King George III’s “absolute tyranny,” after all, is likely to be wary of overreach by its top ruler.

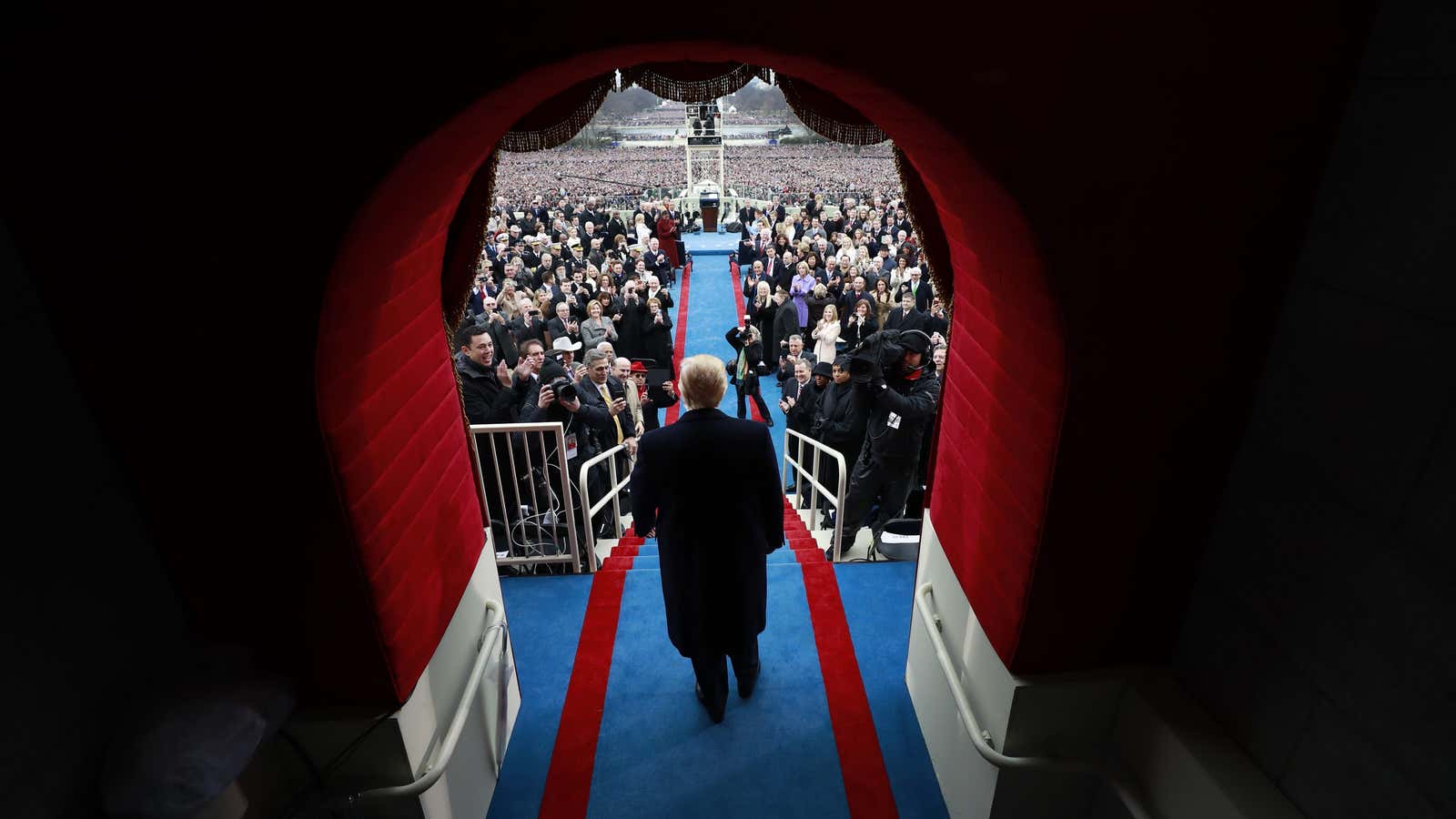

But since Donald Trump’s inauguration this January, those questions have morphed into more serious concerns. As Trump’s increasingly bizarre public conduct raises questions about his temperament and decision-making, and he continues to disregard his own policy experts in favor of advisors with no diplomatic experience, members of both houses of Congress are slowly moving to curb the powers of the office through new legislation. At the same time, state governments are pushing back on some of the president’s demands.

Historical norms, not laws, govern much of what we think of as appropriate presidential conduct, making it especially hard to rein in a US president. There is no law stopping a president from ordering the end of an FBI investigation, for example, or hiring his daughter in the White House, or keeping his private businesses while in office.

Creating new laws is a glacial process, one that can move too slowly to limit abuses as they happen. America’s first president George Washington set the stage for a voluntary two-term limits, for example, which all other presidents after him followed until Franklin D. Roosevelt, who blithely ran and was elected for four terms. In reaction, Congress passed the 22nd amendment, which bans presidents from being elected more than twice—two years after Roosevelt died in office.

“What presidents want is power—the power to do what they want to do,” Theodore R. Bromund, a senior research fellow with the Heritage Foundation wrote this May. The right-wing think tank has been hugely supportive of Trump, staffed up his White House, and essentially wrote his budget, but even Bromund argues Trump needs limits. “If you take that too far, there’s a word for it: tyranny,” he wrote.

The power to wage war abroad

With 2.5 million military personnel, and the world’s most powerful stash of weapons, fighter jets, and battleships at his command, the US president’s role as “Commander in Chief” is technically limited by Congress, which holds the power to “declare war.” But that’s something Congress hasn’t done since WWII, and plenty of presidents have engaged in military action since then.

Only after American soldiers fought and died in the Vietnam War for nearly 20 years did Congress pass the War Powers Resolution of 1973, to “insure that the collective judgment” of Congress and the president would apply when US troops were put in harms way, or where hostilities could be “imminent.” It requires the president to get authorization from Congress in those situations and was only passed after Congress overrode president Richard Nixon’s veto.

Days after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, however, Congress quickly gave the president new military powers. Now these could be rolled back under Trump.

President George W. Bush was given the ability to “use all necessary and appropriate force” against persons or countries who committed or aided the attacks, and to prevent future acts of terrorism, essentially allowing him to bypass curbs if the enemy was defined as terrorists. The Obama administration controversially used these powers to wage military action against ISIL, and they were cited as legal defense when Trump bombed a Syrian airfield in April.

Barbara Lee, a House Democrat from California, has opposed the new powers since they were granted, and introduced multiple, failed amendments to repeal the move since then. But, on June 29 a repeal measure she introduced as part of the defense spending bill unexpectedly passed the House Appropriations committee, with just one of the 52 members voting against it.

Republicans were particularly outspoken in their support. “The Constitution is awfully clear, as my friend points out, about where war-making authority resides,” said Tom Cole, the Oklahoma Republican. “It resides in this body.”

“You have been incredibly persistent and perseverant on this issue for a number of years,” Rodney Frelinghuysen, the Republican chairman of the committee, told Lee. “I think we recognize you, and obviously you have allies in the room. We share your concern.”

The committee vote is just the first step, however. Repealing the powers would need to be approved by the full House, and the Senate, and approved by the president. Already, House speaker Paul Ryan has expressed doubts, saying, “There’s a right way to deal with this, and an appropriations bill I don’t think is the right way to deal with this.”

The power to lift sanctions

US presidents are granted the right to sanction foreign companies and individuals through the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, which itself narrows the powers of a 1917 law. Trump can lift many economic sanctions Obama imposed against foreign countries by a simple executive order.

But in mid-June, the US Senate passed a bill that would impose stiffer sanctions on Russia, and require the president to get Congress’s approval before lifting them.

Sure, as Trump faces multiple investigations into whether he or his campaign colluded with Russia to interfere in the 2016 presidential election, lifting sanctions against Russia wouldn’t be a politically astute move. That’s not to say that Trump wouldn’t do it, however, judging from past events.

The bill passed by 98-2 in the Senate, but its passage through the House has been delayed by technicalities. Some Democrats believe it is being stalled so that it doesn’t pass there before Trump’s meeting with Russian president Vladimir Putin on the sidelines of the G-20 this week, because it could undercut Trump’s negotiating power. The White House is lobbying (paywall) for the provision requiring Congressional approval to be removed.

The power to collect voting data

Nearly 30 of the US’s 50 states have rejected a request from Trump’s Presidential Advisory Commission on Electoral Integrity to provide names, addresses, voting records, birthdates, social security numbers, and party affiliations of registered voters. The commission was established to investigate voter fraud, which the Trump administration says was widespread in the last election but which local election authorities and elected officials from Republican and Democratic parties both deny.

The rejections were often angry, with one Republican secretary of state telling the commission it could “go jump in the Gulf of Mexico.”

What Congress and the states can’t limit

As Congress inches toward possible permanent legislative limits on presidential power, and state officials spar with the Trump White House, Trump has managed to wield plenty of authority.

Most significantly, Trump has overseen the most significant destruction and rollback of rules and regulations possibly ever conducted by a US president. After Congress voted in almost all of his cabinet heads, many have begun upending the departments they run, slashing employees and changing the agency’s purpose completely. Environmental Protection Agency Scott Pruitt, for example, is enlisting advisors from the fossil fuel and manufacturing industries to help make policies on pollution and dangerous chemicals. The EPA is already offering staff buyouts that are expected to cut thousands of jobs there, and Pruitt plans to set up a unit to challenge climate science.

Under attorney general Jeff Sessions, the Department of Justice has already had a sweeping impact, re-instituting the “war on drugs,” backing hardline anti-immigrant policy, and weakening police reform.

Constitutional experts who railed against Obama’s liberal use of executive orders during his presidency, and Bush’s before that, say the concern over Trump’s powers illustrates that the presidency has been too strong for some time now. “To all my newly-fervent defenders of the Constitution from the left: Welcome back,” Michael Munger, a professor of political science at Duke University wrote at Quartz. “Perhaps it’s time to accept that limiting executive power is a cause we should all fight for—no matter what side we’re on.”