22 million children in the world’s 73 poorest countries go unvaccinated every year

When children in poor countries were missing out on basic vaccines, a consortium of health advocates found an ingenious way to cover the cost—by tapping the greed of the global bond market and the altruistic impulses of institutional investors.

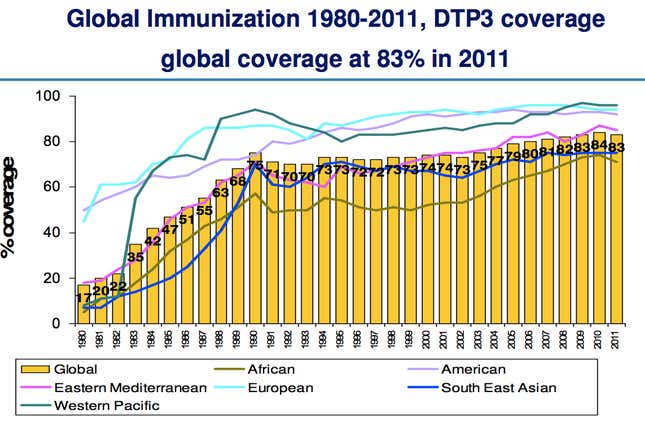

In the 1990s, the percentage of children receiving vaccines around the world began to stagnate, and poorer countries missed out on the health and economic benefits from relatively simple immunization programs that are common in the wealthier parts of the world.

The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (now the GAVI Alliance) was founded in 2000 to reverse this trend. Funded by grants from governments and the private sector, its brought together stakeholders like the World Health Organization and UNICEF to help poor countries purchase and distribute the vaccines, “graduating” them out of the program when their gross national income per capita goes above $1,550. That mechanism came to include aggregating poor countries into a single large buyer that could negotiate discounts with pharmaceutical companies.

The structure proved successful, but by 2006 it was clear the organization would need more funding to meet Millenium Development Goal deadlines for vaccinations by 2015. So it came up with a plan to borrow the money.

How to invest in a vaccine

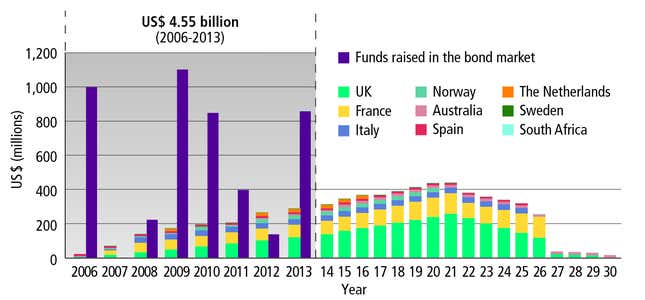

With the help of nine countries, GAVI set up the International Finance Facility for Immunisation. IFFIm is a structured-finance vehicle, like the mortgage-backed securities that blew up the economy in 2008. In this case, the intent isn’t to turn tomorrow’s mortgage payments into cash today, but to turn future donations into vaccines today. The cash flow comes from long-term donation contracts, often twenty years or more, signed by the nine nations, including the UK, South Africa, and Australia.

With the surety of those contracts, IFFIm can borrow money from world markets. In 2006, it issued an inaugural $1 billion bond, which gave it the funds to begin scaling up. Other issuances followed, including sales to Japanese retail investors looking for securities denominated in foreign currencies; its 2008 issuance was the then-largest ever in the market and was credited by Euroweek with kick-starting a trend of socially responsible investing there.

Last week, the organization issued a US$700 million bond—its first with a floating interest rate, at Libor + 19 basis points—that was bought by investors around the world.

The growing super-sovereign social responsibility market

The buyers of these “vaccine bonds” are often big institutional investors, looking for well-rated securities that can fill out a socially-responsible portfolio. In the last several years, investments like these benefitted from the hunt for yield in a low-interest-rate world, and their yields, volume and frequency have all been rising.

“We could be putting this in Fannie or Freddie debt [i.e, US mortgage-backed securities], so why don’t we do something where we’re making more of a positive impact and a couple extra basis points?” says Benjamin Bailey, a portfolio manager at Everence Financial who took part in last week’s offering.

Similar socially-conscious schemes include Green Bonds from the World Bank, development bonds issued by the International Finance Corporation, and project-based financing for renewable energy operations or advancements in water and sewer systems. David Ferreira, GAVI’s managing director for innovative finance, got started in the field funding the expansion of water infrastructure in post-apartheid South Africa.

What about a world of rising rates?

But two trends may be worrying for IFFIm. One is trouble in the euro zone—particularly the downgrade in April of the UK’s credit rating, which meant a similar downgrade for IFFIm’s bonds because the bulk of its donations come from the UK. That downgrade means a higher cost of borrowing. With its largest donors trying to cut spending, a worst-case scenario could result in less cash than IFFIm and its lenders expect. Still, investors are confident in the strength of the contracts—which ensure governments can’t evade their obligations easily—between IFFIm and its donors, and the conservative cash management performed by World Bank on the organization’s behalf.

The other challenge will be to remain competitive if interest rates start to rise, luring investors away to more conventional places to put their money, like government bonds. But Steve Liberatore, a portfolio manager responsible for some $5 billion in socially responsible fixed income investments at TIAA-CREF, says the market for these kinds of bonds is sturdy enough to withstand the tougher market conditions. IFFIm’s latest deal, with a floating rate and global subscription, demonstrates that socially responsible bonds can offer a liquid investment with yields that won’t fall if rates rise.

Problems to solve

The impact of the vaccine bonds has been fairly clear: 370 million additional children have been vaccinated, and the World Health Organization directly attributes the fact that immunization rates have risen again since the nineties to GAVI. Most of the spending has been in places like Nigeria, Ethiopia, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

“We actually do something: Money to immunize kids in the poorest countries across the world, literally saving lives in a fixed income structure,” Bailey says.

The structure is being considered to help solve other problems, from climate change to rainforest deforestation, according to Liberatore.