Last will and testament

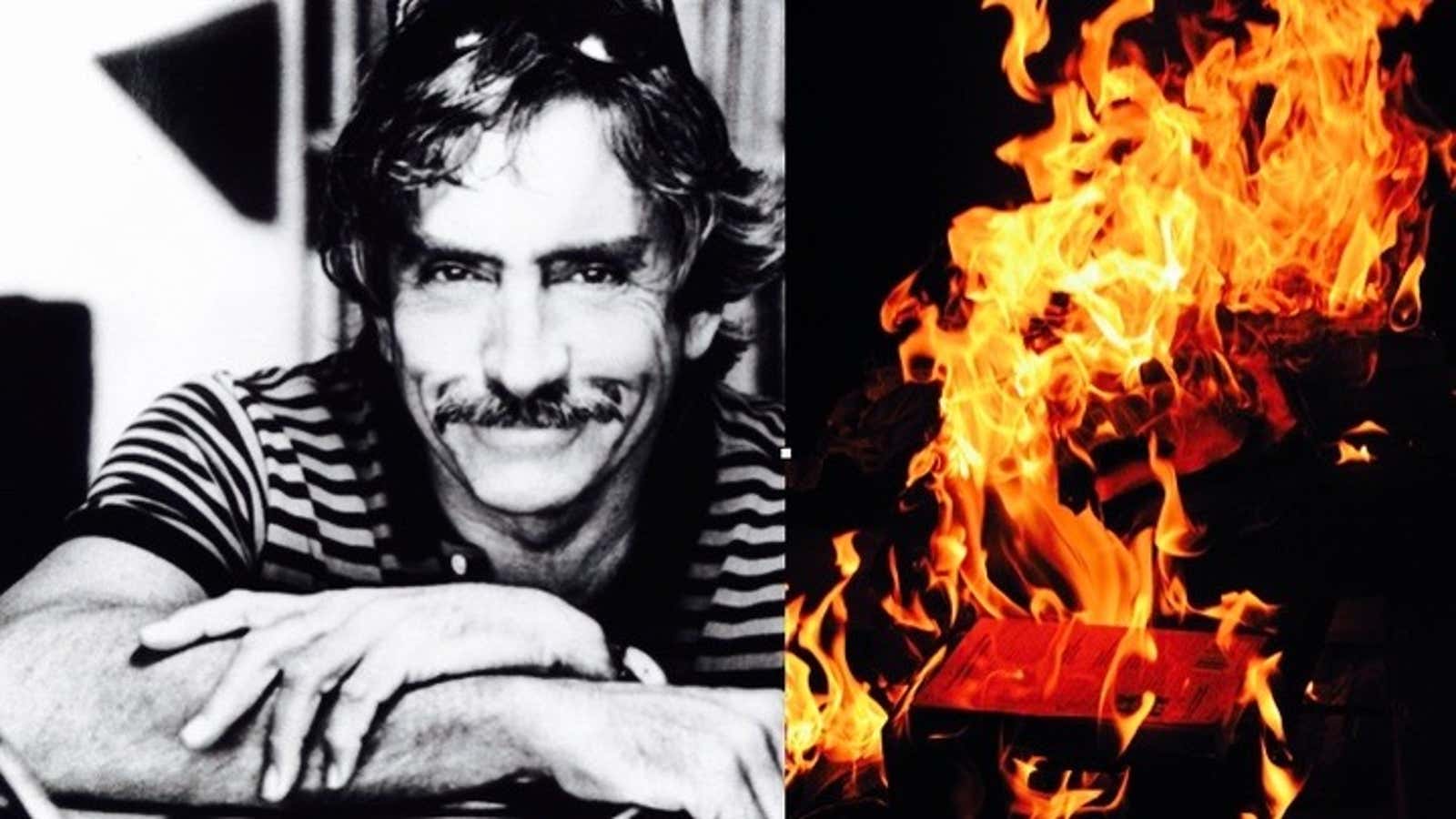

I, Ephrat Livni, being of sound mind and memory, do hereby declare this to be my last will and testament. Following in the footsteps of Franz Kafka and Edward Albee, I direct the executor of this Will to destroy my writing.

Specific requests

Burn the words. Disappear drafts. Leave no trace of my mistakes.

First declaration

The intellectual property of a writer is theirs to dispose of as they see fit in life and death. The law recognizes this, even if the culture doesn’t always. As such, writers much greater than I have felt free to deprive the world of their work.

Take Albee, for example, whose will states:

If at the time of my death I shall leave any incomplete manuscripts I hereby direct my executors to destroy such incomplete manuscripts.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning American playwright—perhaps best known for the 1962 work Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?—died in 2016. A perfectionist not inclined to share anything less than his best, most polished writing, Albee presumably wanted to ensure the quality of his full body of literary work. The question is about the one play he left unfinished, the one that never made it to the stage because he was still tinkering with it.

The Albee estate hasn’t yet said what it has done, if anything, with the work. But it has disposed of his art collection, auctioning it off just as instructed in the will, and has otherwise complied with his directives. It would seem the one about his writing was likely at least as important to him as the one with instructions about art he acquired.

Second declaration

Fans are clamoring for more Albee, claiming the writer’s process and problems are precisely what they want to see. Writing professor David Crespy of the University of Missouri, president of the Edward Albee Society, told the New York Times:

Am I disappointed? Yes, because every tiny bit of everything that a writer has written provides insight into that writer’s creative process. But am I surprised? No. He maintained very strict control over the materials that were available to the public.

Arguably, the writer’s request is against the public interest, but that is not a legal argument, just cultural and with no weight in court. Should Albee’s directive be honored? If it isn’t, it wouldn’t be the first time an estate ignored a writer’s wishes for the sake of literature.

Precedent

Franz Kafka destroyed most of his writing before his death in then-Czechoslovakia in 1924, and he ordered anything left burned afterward. If it wasn’t for his disobedient friend and literary executor, fellow writer Max Brod, we would not have The Metamorphosis or The Trial, or the word “kafkaesque” to describe bureaucratic oppression and dreary nightmares.

Kafka directed Brod to destroy whatever was left in a letter, writing:

My last request: Everything I leave behind me…in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches and so on, to be burned unread.

Brod promptly ignored Kafka and went about securing him a place in history. He ensured Kafka’s novels and letters were published, and is responsible for the writer’s fame.

Cultural claim

Ironically, Brod’s defiance spawned a kafkaesque lawsuit in Israel—a country that did not exist at the time of Kafka’s death. Kafka was Czech and Jewish. He left no descendants and expected to leave no writing. But some of his papers became the subject of a dispute between the Library of Israel and Brod’s estate after Brod died in Israel in 1968.

The state essentially claimed Kafka for the Jewish culture, arguing that his papers—documents in one of Brod’s suitcases—belonged in the Library of Israel, based on things Brod had written in early statements and documents, and Brod’s expressed zionism. But Brod’s estate argued otherwise, based on his will.

The state and the estate battled for more than half a century. The nine-year lawsuit finally concluded late last year, with the Israeli Supreme Court ruling in favor of the library. Kafka’s documents now belong to the state and not Brod’s heiress.

Final declaration

Kafka would not have approved any of this, surely. Still, Brod did the world a service. It was perhaps fitting for such a grim writer to think his work didn’t matter, but Kafka’s friend gave the world a gift, and a rare one. There are many writers but few have such a unique and culturally indispensable worldview that their work spawns a word of their own, still in use a century after their death.

As for Albee, he, like Kafka, has made himself clear. But with all due respect to last wills and testaments, the estate might contemplate the story of Kafka and Brod and reconsider. The people want to read the play. And anyway, who’s afraid of dead writers?