Binary Capital is now the cautionary tale.

Within days after the venture capital firm’s co-founder Justin Caldbeck was accused of sexual harassment by a number of women in a report by The Information (paywall), Caldbeck announced his departure. Limited partners of the fund started bailing soon after. In less than a week, Binary Capital’s second fund was in danger of being canceled and it may now be forced to wind down its operations and sell off its equity stakes (Binary did not immediately respond to multiple inquiries).

For perhaps the first time, men in Silicon Valley are paying a price—defined in dollars and cents—for bad behavior that includes everything from groping to verbal disparagement. Such sexism has been pervasive for decades, many women say, and those brave and wealthy enough to bring a case to court have usually lost. But going public with documented evidence now seems to be getting real results and creating a chill among some male investors used to exploiting a power imbalance between female startup founders and investors.

“The gig is up,” writes Joanne Wilson, a New York angel investor, who has heard stories for more than decade from female founders about indecent behavior by male investors ranging from propositions of hotel room trysts to refusing to invest in women who want to have children. “It’s certainly a different reaction than we’ve ever seen before,” Janice Fraser, a startup founder in Silicon Valley since the 1990s, said in an interview. ”It is unprecedented in my lifetime.”

None of the dozen female tech company founders and investors that Quartz talked to believe the atmosphere of sexism that pervades the tech venture capital world is going away. “The women venture capitalists in this industry have been hearing stories from female entrepreneurs for well over a decade about the behavior of their male colleagues,” says Claudia Iannazzo, the managing partner and co-founder of venture firm AlphaPrime, as well as Parity Partners, which helps venture firms find qualified female job candidates. “Until firms set themselves diversity targets or start hiring women, as far as I’m concerned, it’s still all talk.”

But there’s a palpable sense that things are starting to shift. What was acceptable, or overlooked, a month ago is now derailing careers and upending venture funds. Here’s how life for female founders is changing in Silicon Valley, and what may be to come.

Sexual harassment is now an existential risk for venture firms

Denial and apologies are no longer enough. Since former Uber engineer Susan Fowler posted a harrowing account of blatant sexism and harassment at the ride-sharing company, more women in tech have aired their experiences. While in the past such accusations were seen as a nuisance or, at worst, a potential lawsuit, “now it’s literally an existential threat,” says Robbie Goffin of FTI Consulting, who advises on risk and communication issues with venture firms in Silicon Valley.

“It’s not about being sued,” Goffin says. “They’re worried about ever being able to do business again. The question is not whether you’ve done something illegal. It’s whether you’ve done something unethical.”

Binary Capital isn’t the only firm to melt down. Following revelations of harassment in The New York Times, Dave McClure, the founder and CEO of tech incubator 500 Startups, was forced out. One of his female partners, Elizabeth Yin, then stepped down in protest at how the firm dealt with McClure’s behavior.

It will likely not be the last instance. For now, sexual harrasment of female founders has an implicit price tag: out of business.

Responses to sexual harassment take days, not months

The swiftness of the fallout has been unprecedented. The accusations against Caldbeck were published by The Information on June 22. Within three days, Caldbeck announced he was taking an indefinite leave of absence and seeking counseling. By week’s end, major investors behind the fund had moved to withdraw funding commitments (paywall) and at least one entrepreneur was reportedly demanding Binary “terminate their board relationship.” McClure of 500 Startups formally resigned just three days after accusations against him were made public (similar allegations had surfaced internally months prior).

Well-known investor and billionaire Chris Sacca of Lowercase Capital preemptively apologized for his behavior in a post on Medium after being contacted by The New York Times just before the newspaper’s harassment story appeared online June 30.

It’s now clear the sequence of responses to sexual harassment reports has been dramatically compressed.

The more typical case had been that of Ellen Pao. The former partner at the venture firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers in San Francisco filed a lawsuit for gender discrimination and retaliation against her employer in May 2012 after years of internal complaints. Following the multi-year saga—the jury ultimately decided against Pao—she left to create Project Include to help companies and investors diversify their workforce.

More women are likely to speak out

The recent results suggest that the balance of power has shifted between accuser and accused. Not by much. There is still mostly risk and downside for women who speak out, but there is also a sense that speaking out will no longer permanently jeopardize a woman’s career.

Fowler demonstrated how to do it. As my colleague Ali Griswold noted, in her account of her Uber experience, she documented everything, wrote a dispassionate blog post, alleged nothing that occurred at a social event with alcohol, and came out against a company with a toxic track record. Many other women have spoken up about discrimination in tech only to be silenced or forgotten, and firms still buy employees’ silence through severance packages, as well as confidentiality and non-disparagement agreements.

A new generation of young professional women is no longer willing to go along. “This generation has much more confidence in their hire-ability and long-term career potential,” says Fraser. They have “more confidence that they deserve not to have this sort of thing present in their professional lives.”

Leveling sexual harassment charges remains risky. Women still face the threat of explicit reprisal or lose the chance at funding by being shut out of the tight-knit venture community. ”I understand the feeling to want to keep your head down, be an example of success, and not do anything to make it harder to raise funds,” says Melissa Pancoast, the founder of a fintech startup. “The power dynamics are so awful that if you’re trying to keep your company alive you’ll put up with all kinds of shit.”

But Pancoast says for at least three years, female investors and founders have been having dramatically more open conversations about shared cases of discrimination. The sense now is that enough people are supporting them that even if it damages their business prospects, it won’t doom them. The growing female founder community, and increased sharing on social media and blog posts, has contributed to a sense that it’s no longer acceptable to remain silent.

Ashley Swartz, founder of enterprise software startup Furious Corp., says more examples will likely come to light. ”For women who come out [about sexual harassment], dimes to dollars it was not the first time,” says Swartz. “They just wanted it to be the last time.”

Venture capitalists are responsible for their partners’ behavior

Partners are increasingly seen as complicit in the actions of their colleagues. For years, it has been surprising how investors’ behavior has been ignored by colleagues in an industry ostensibly known for due diligence.

With the (pending) resignation of Caldbeck’s partner Jonathan Teo at Binary, and departures of key executives elsewhere, that may change. There are a raft of new pledges being drafted such as LinkedIn co-founder and Greylock investor Reid Hoffman’s “decency pledge” that promises to make this explicit: a zero-tolerance policy for sexual harassment; a clear separation between romantic and business relationships between investors and founders; and disclosure of information to colleagues as appropriate. Several firms have rallied behind it.

Will a voluntary pledge change any of this? “For marginal actors, it’s crystal clear there is now a line that you can no longer cross,” says Goffin. But no major firms have faced such a scandal in recent months. That will be the test.

Limited partners are now monitoring the conduct of the venture funds they back

Without limited partners (LP), the institutional and family funds that give venture funds money, venture capital doesn’t exist. LPs may now take a more active role in policing the sexist behavior of their firms.

The largest LP trade group—the Institutional Limited Partners Association—plans to address these issues in a new principles document later this summer, Axios reports. Bloomberg Beta founding partner Karin Klein also called for LPs to insists on better gender representation in venture capital on June 13. “We’re simply asking that we VCs begin to collect the data and that LPs ask us for it — a sort of transparency pledge,” Klein wrote.

LPs have real power. They often have “key man” language making their investments conditional on the “value, insights, and connections” of a partner. If a key person leaves, investors can as well. But their most important leverage is choosing the funds where they place their money.

LPs need to use that power if things are going to change, says Iannazzo of AlphaPrime. “I think that’s just being decent,” she says. “Who wants to invest money in people who are indecent?” Now, that may be a business risk as well.

VCs may no longer proposition founders by text message

If you attend a gathering of female founders, and the conversation of sexual harassment comes up, phones often come out next revealing a litany of text messages, Facebook chats, and other digital evidence that documents years of off-color and harassing messages from investors to female founders seeking funding.

McClure of 500 Startups wrote to entrepreneur Sarah Kunst on Facebook after a meeting in which the subject of working at the fund surfaced: “I was getting confused figuring out whether to hire you or hit on you,” he wrote according to The New York Times.

Similar messages were key in proving incidents at Uber, Binary Capital, and others. Many investors may now think again before texting and messaging propositions to female founders.

Firms treating female founders poorly will lose deals

The bottom line hurts VCs most. Aileen Lee of Cowboy Ventures, one of Silicon Valleys’ few female-led firms, knows where to aim. When her companies need follow-on funding, she has said she will steer her most promising portfolio startups toward “modern venture firms that have women and people of color in investing positions,” according to TechCrunch. Although women lead just a tiny fraction of venture-backed companies, the number is growing, and with the new pledges, it’s possible men will join them in shunning funds that discriminate against women.

The thinking is simple, Lee said. “Why should we make money for assholes?” she asked.

More firms may follow her lead.

Men are now reaching out to support female founders

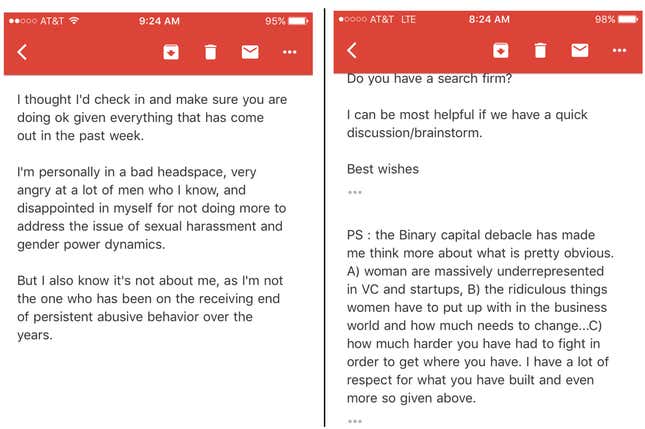

For the first time after an incident of sexual harassment, Pancoast said “our [male] investors are reaching out to us now.”

Tracy Lawrence, founder of Chewse, noted a similar phenomenon when two of Chewse’s male investors personally emailed her after the news broke of recent incidents. “I don’t want to exclude men,” she wrote on Medium July 1. “They are our greatest advocates. That’s half the population to help bring more fairness to a broken industry.” She added screenshots of her investor emails.

Women may now be (even more) excluded from social opportunities critical to fundraising

Exclusion, as much as sexual harassment, can damage a female founder’s prospects at success. One entrepreneur called it death by a thousand paper cuts: not being invited to dinner, not being asked to sit on boards, not joining nights out at the bar.

Jessica Mah, founder of accounting startup inDinero, notes that much of early-stage investing happens in bars, restaurants, and social situations. ”People who are celebrating are clearly doing too much too soon,” says Mah, who has fielded calls from multiple investors nervous about how to handle their interactions with female founders. “People are not thinking about downstream consequences. … A lot of my money I raised is hanging out over drinks. You don’t want to take that away.”

Pancoast agreed female founders face an impossible choice. She mentioned female friends who don’t take meetings after 5pm or drink in professional settings. ”What’s damning about that is that’s where business gets done,” she says. The test for investors will be whether women are sidelined from social events, effectively punishing the female founders for reporting sexual harassment.

Silicon Valley culture seems unlikely to change while so few women hold positions of power

Change happens when power is shared among more than one group. At the moment, venture capital is almost exclusively male. Only about 6% of senior venture capitalists are female, down from 10% since 1999 according to studies by Babson College and Columbia University. At venture-backed startups, only 2.7% of companies had female CEOs.

There’s a sentiment that not enough qualified women exist. Michael Moritz, chair of Sequoia Capital, told a Bloomberg reporter in 2015 that what “we’re not prepared to do is to lower our standards” in response to a question about why the firm had no female investing partners in the US. He later added, “but if there are fabulously bright, driven women who are really interested in technology, very hungry to succeed, and can meet our performance standards, we’d hire them all day and night.”

The insinuation is wrong, says Iannazzo. More than enough qualified women exist. They’re just harder to find because most social networks in the venture industry are predominately male. Iannazzo’s own venture firm, AlphaPrime, is evenly split between men and women as the result of a concerted recruiting effort. “It took about a week of telephone calls and unconventional thinking to identify the same number of exceptional women candidates,” she wrote in a Medium post. “In the end, we’ll have no problem bringing on equal numbers of both.”

That, she argues, is the path to change. “Culture only truly shifts once more women are in power,” says Iannazzo. “It’s not the vocabulary of the industry that’s the problem. It’s the gender of the industry.”

The image above was taken by Web Summit and shared under a CC BY 2.0 license