The new service Lyft is testing in Chicago and San Francisco is unlike anything the company has tried before. It can still be hailed on-demand at the touch of a button and it groups people into cars along common travel routes. But the new service doesn’t come to your door. It costs $3 to $4 per ride, and it picks up and drops off at the same stops every day.

Lyft calls it Shuttle. The internet calls it a bus.

While Uber made its name with private rides, Lyft has always had one eye on mass transportation. Years before they started Lyft, co-founders Logan Green and John Zimmer built Zimride, a carpooling service for undergraduates. They sold Zimride to rental car company Enterprise for an undisclosed amount in July 2013, around the same time that Lyft, still sporting pink mustaches on every car, celebrated its first birthday.

Quartz spoke to Lyft director of transportation Emily Castor this week about its work on Shuttle and public transit in general. We didn’t hesitate to ask the tough question: Is Lyft Shuttle a bus? The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Quartz: Lyft has experimented with a bunch of different pooled or transit-like products. What was the predecessor to Shuttle?

Castor: This is quite different, I guess, than anything else we’ve done. You could certainly say that it descended from Lyft Line, which we continue to operate.1 You might also be thinking of Lyft Carpool, which was quite different.2 There’s always experimentation happening at Lyft with different flavors of ways to match people up with rides. Carpool was more focused on commuters and casual carpooling drivers, and Lyft Shuttle is more similar to Lyft Line.

Shuttle is really motivated by the desire to create the most streamlined efficient commute experience possible and to attract more people to carpool on their way to work. If you look at commuting in this country right now, it’s a pretty sad picture. Seventy-six percent of people drive to work alone. Something is fundamentally broken in that system. A big part of that is the fact that transit has had a very limited set of tools for a long time. You either had 40-foot buses or you had trains, or a couple variations on those. But there were certain environments where neither of those was going to be able to deliver the convenience and the travel time that people wanted, and so you end up with the vast majority of American commuters opting out of public transit.

Shuttle was skewered on social media for being a bus. Why don’t you consider it one?

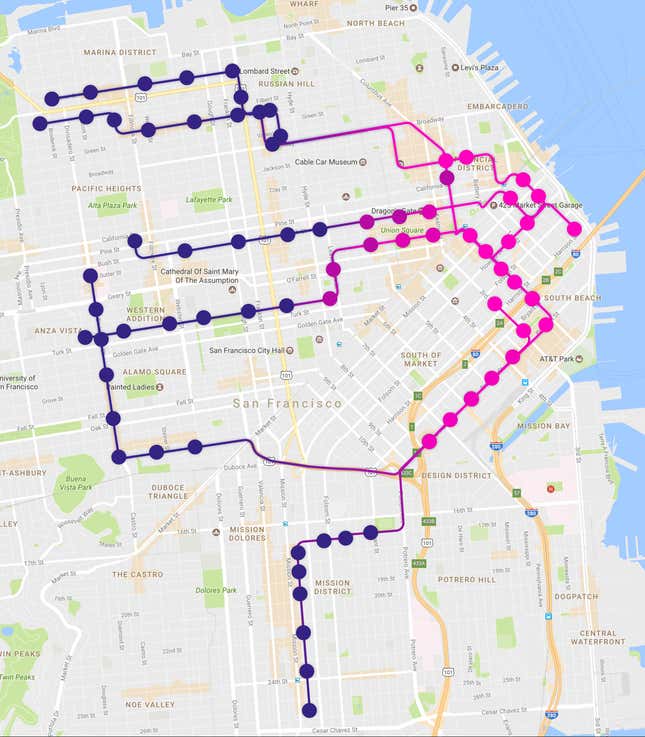

What we’re seeing right now is that there’s an emergence of a huge variety of microtransit services that are different ways of creating high-occupancy rides. Chariot, Via3—I don’t want to name-drop a lot of other brands—there’s an explosion of a variety of services that are using their creativity and the new potential that’s created by smartphones and GPS and finding ways to match people up with different types of vehicles on different types of service delivery patterns to try to attract marketshare away from people who own their own cars.

These are not heavy-duty vehicles. They’re standard passenger cars that people own that are already operating on the Lyft platform.4 That means they’re not giving Shuttle rides unless there is demand for one, which I think is one of the key features of Shuttle. One of the big problems that transit services face is that it’s really expensive for them to just have a driver running a route all the time, especially if they don’t have enough riders to fill up that bus. It greatly improves the financial viability of offering that service if you only have to offer it when somebody needs it. That’s how Shuttle operates. It’s very efficient in only providing service when it’s required.

Do you see yourselves as a complement to public transit?

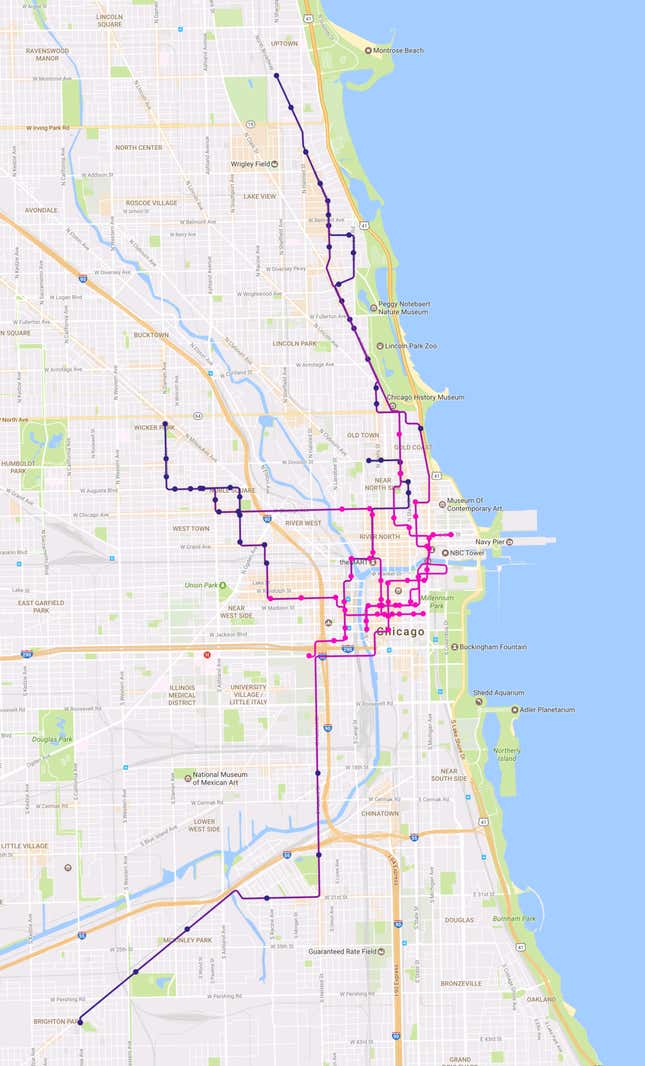

Absolutely. In some cases, a part of public transit. We want to have an open dialogue with those transit agencies so that we know where we can be the most helpful. For example, if you look at the Shuttle routes in Chicago, you’ll see there’s a route that goes down through Brighton Park, which is a low-income, underserved community that actually lacks a good transit connection into downtown, where most of the jobs are. Shuttle is really a product that’s allowing us to test out where Lyft can be the most helpful. We felt that was an area where people do need help with improving mobility access.

It’s frankly happening all over the country. In the last couple of years, this conversation has developed very very quickly. As soon as Lyft started to become a permanent fixture of the transportation ecosystems in these places, I started to have conversations with transit agencies and it very quickly turned into this kind of creative brainstorming about how can we actually use these new products to become part of the way the transit agencies operate, and tackle some of those really hard use-cases that they haven’t been able to do in the past.

Paratransit is a service that transit agencies are mandated to provide to individuals with disabilities. It’s very challenging, and yet those communities are the ones in the greatest need of mobility access. Transit agencies have had a difficult time providing that on a cost-effective basis in the past. It can be $60 a ride, per person. Those are prime categories of transit service where there is a shared interest both from the riders, who depend on that service, and from the transit agencies, who need to find a more sustainable way of offering that service and to actually expand the amount of service that they provide, to partner with a system like Lyft.

Do you feel like Lyft has an advantage in talking to cities over Uber because you’ve positioned yourselves as the friendlier, more collaborative of the two big companies?

Lyft’s culture and our values have always been a key part of our success, and that’s true now more than ever.