China’s censors are making sure the country doesn’t remember human rights activist Liu Xiaobo

Liu Xiaobo will be remembered by the world as the Chinese human rights activist awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. He’ll be remembered by many in China, if at all, as a man jailed for subversion of state power. China’s censors are making sure of it.

Liu Xiaobo will be remembered by the world as the Chinese human rights activist awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. He’ll be remembered by many in China, if at all, as a man jailed for subversion of state power. China’s censors are making sure of it.

Liu died from organ failure after a battle with liver cancer at the age of 61 last night (July 13) in the northeastern city of Shenyang, where he had been imprisoned for nine years. Authorities had moved him to a local hospital for treatment three weeks before his death, but had rejected pleas to let him travel abroad for better care.

While media outlets around the world covered Liu’s plight and condition over the past three weeks, in China, news has been limited. Much of the information received in China is from state-controlled media, which rarely reported on Liu’s condition. One of the few sources of updates was the hospital treating him, which released 14 brief statements (link in Chinese).

State wire Xinhua reported Liu’s death in English yesterday, noting in a two-sentence piece that he had been ”convicted of subversion of state power.” An opinion piece in English today in the Global Times, also state-owned, said that “Liu’s last days were politicized by the forces overseas. They used Liu’s illness as a tool to boost their image and demonize China.” The headline described him as a “victim led astray by West.”

Meanwhile on its account on Weibo, a social network, the Global Times yesterday posted a comment—since removed—that some saw as making light of Liu’s death. It suggested they’ll be enjoying watermelon (a meme in China suggesting gloating or indifference) while others mourn.

On China’s internet, censorship has made it hard to talk openly about Liu. Search terms like “Liu Xiaobo” and “Liu Xia” (Liu’s wife) don’t work on Weibo, which has over 300 million users. Also blocked is “I have no enemies,” a famous statement Liu made in late 2009.

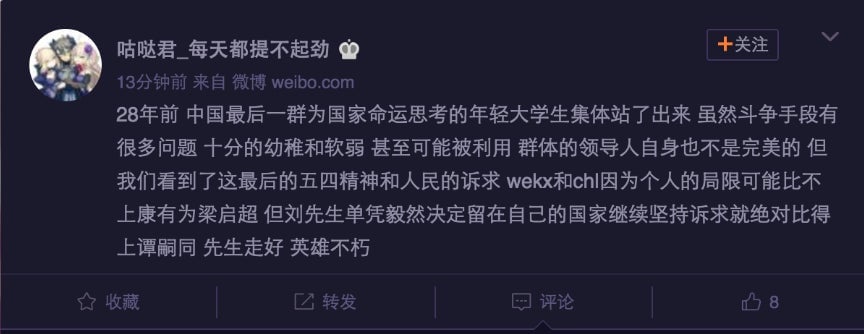

The censorship effort was in full force last night after Liu’s death. On Weibo some managed to express mourning using the phrase “Mr. Liu” (in Chinese), but that was soon blocked as a search term, too, and posts with it were deleted. A search attempt brought: “The result was not displayed, according to related laws and policies.” Ten posts with the phrase spotted by Quartz last night were taken down. One described Liu as a hero who had fought for the people.

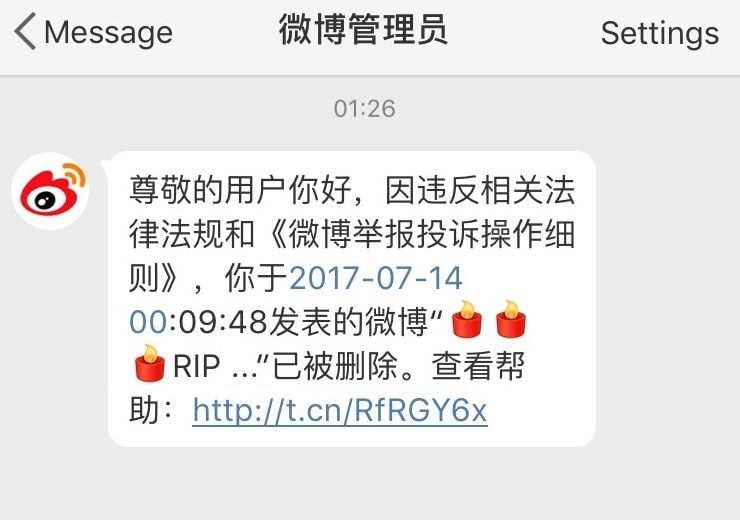

Since last night, Weibo has also indicated that creating a post with a candle emoji or “RIP”—even if Liu isn’t mentioned—is a “violation of laws and regulations.”

Other keywords translating to “compassion release,” “late-stage liver cancer,” “Liaoning prison,” and “an empty chair” are among the only still available (so far) for news about Liu. “Empty chair” refers to Liu’s absence at the 2010 Nobel Prize award ceremony.

Weibo did not reply to Quartz’s request for comments.

It’s possible, of course, that China’s censors have missed some other search terms being used to talk about Liu. But if so, they are no doubt looking for them.