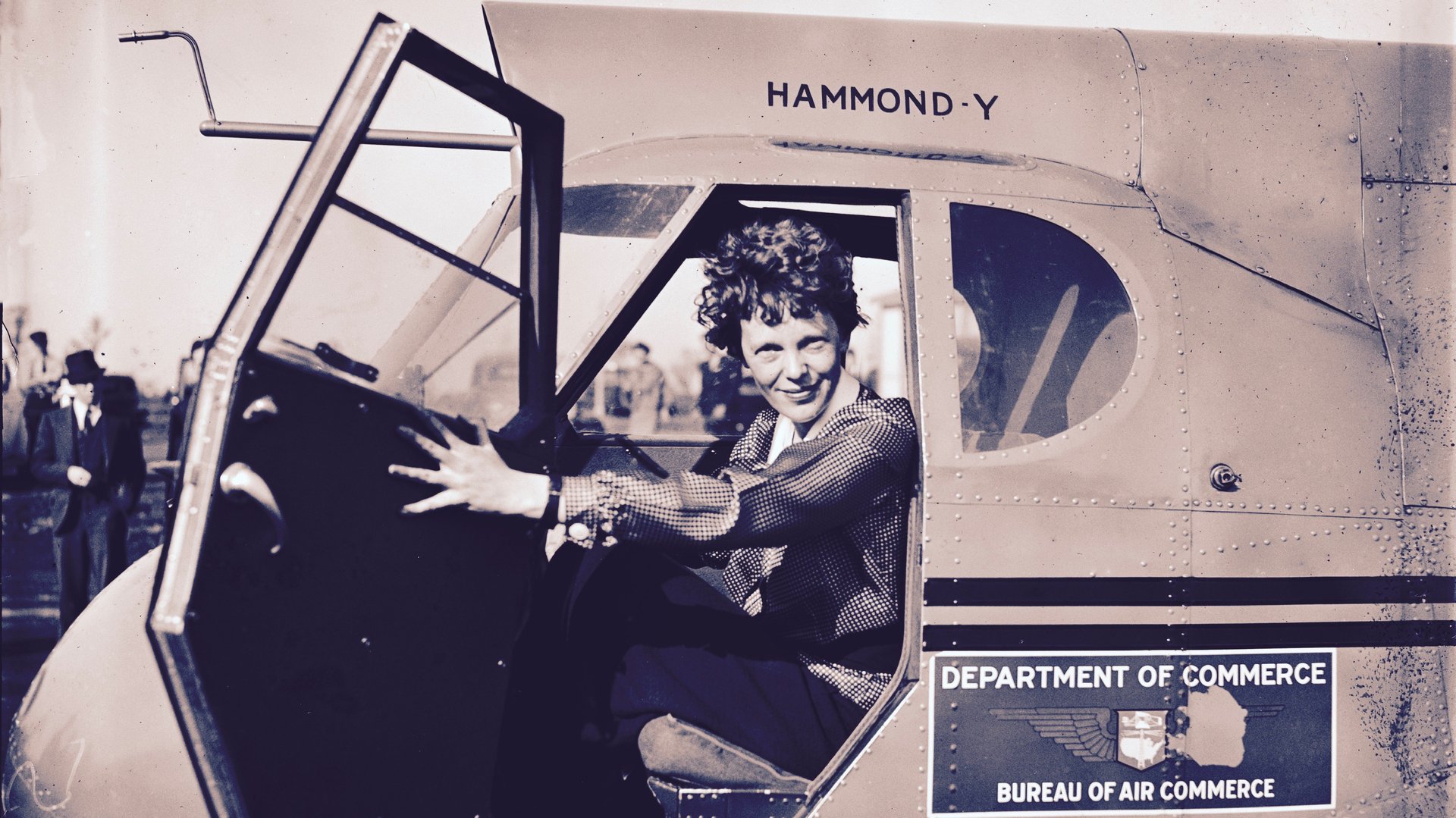

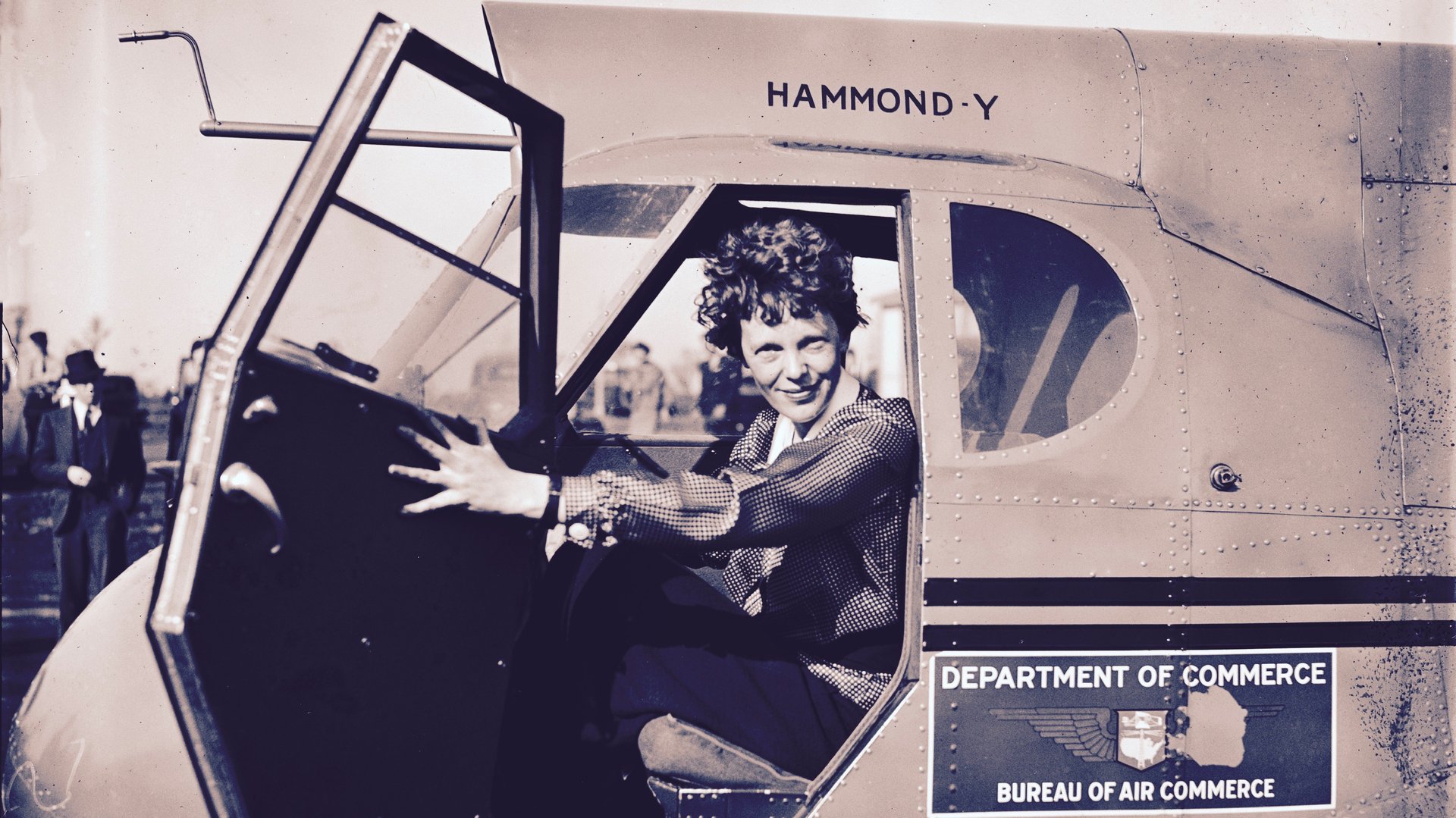

In 1932, Amelia Earhart told the New York Times to quit calling her “Mrs. Putnam”

Dear Ms. Earhart:

Dear Ms. Earhart:

We have received your request and write from the future to reassure you that you’re known all around the world only by your flyer’s name, Amelia Earhart. No one knows Mrs. Putnam. To the extent that your husband, George Putnam—once a well-known publisher—is mentioned at all these days, it’s because of your flying fame.

You wrote to the New York Times in 1932 to request that the newspaper stop referring to you as “Mrs. Putnam” and instead use your given name, Amelia Earhart. That’s the appellation you used professionally before marriage. You noted then that the “privilege” of a married woman using the given surname that she used to make a name for herself was granted mainly to women writers and actresses.

Just so you know what’s been happening since then, well, working women faced the same name challenge you did for another half century. Use of the word “Ms.” for married women maintaining their surname professionally or legally (as opposed to Miss for unmarried women and Mrs. Husband’s Name for the wed) only began to take hold in the 1970s. It didn’t gain widespread acceptance until the subsequent decade.

Under common law, a married woman was not compelled to take her husband’s surname (pdf). Still, custom did dictate it and some states deprived women of rights if they did not, like retaining their driver’s license and voter registration. In 1975, the Supreme Court of Tennessee in Dunn v. Palermo struck down a law requiring that a married woman register to vote under her husband’s surname. By the mid-1970s, these legal restrictions were generally overturned or ignored.

But the culture was still struggling to accommodate change. Increasingly, women were working and attached to their original identities for branding purposes—and that applied not just to famous flyers and writers. Use of the word “Ms.” became official at the New York Times on June 20, 1986. The paper announced its new policy then as follows:

Beginning today, the New York Times will use ‘Ms.’ as an honorific in its news and editorial columns. Until now, ‘Ms.’ had not been used because of the belief that it had not passed sufficiently into the language to be accepted as common usage. The Times now believes that ‘Ms.’ has become a part of the language and is changing its policy. The Times will continue to use ‘Miss’ or ‘Mrs.’ when it knows the marital status of a woman in the news, unless she prefers ‘Ms.’ ‘Ms.’ will also be used when a woman’s marital status is not known.

By the 1980s, more women were opting not to take a married name at all. A 2004 study (pdf) in the Journal of Economic Perspectives looked at women’s surnames in the New York Times Sunday Styles pages and wedding announcements from 1975 to 2001. There was a major rise in women keeping their surnames and deciding not to adopt their husbands’ names. Only 2% kept their surnames in 1975, and 4% in 1976. By 1980, about 10% of women did. That rose to 20% by the mid-1980s.

Now, about a third of brides maintain their surnames. Still, the question of whether to take a husband’s name, and how to refer to a married woman, remains an issue for many. Of the 30% of women who maintain their given surname, about a third choose to hyphenate, thus combining their husband’s name with their own to merge their old and new identities.

Some couples decide on a hybrid name of their own creation, made up of both of their last names. In such cases, they both adopt new identities with the marriage. That doesn’t solve the branding problem, however, and leaves both members of the couple ordering new business cards, passports, licenses, and more.

Very commonly, women keep their given surname in a professional context and officially adopt their married name legally, either to ensure that they share the same last name as their children or to honor tradition. Regardless of why they choose to do it, the two-name system isn’t perfect.

For example, Yen Ha, founder of Front Studio Architects, told Quartz that recently, when she was a visiting professor at a university that handed out email addresses based on legal names, the school gave her an email address based on her married name. Only, while she had indeed changed her legal surname to that of her husband, she goes by her given surname professionally. She asked the administration to change her email all semester, yet the school did not relent.

From an administrative perspective, a name change can be a major hassle. In America, it means switching up your important documentation and contacting many bureaucracies we usually try to avoid, like the Department of Motor Vehicles or the Social Security Administration.

More fundamentally, there’s the question of identity. We may be much more than our names but, as you noted in 1932, it’s strange to become someone new, say “Mrs. Putnam” instead of “Ms. Earhart.” That’s especially true after working so hard to become you. But we don’t have to tell you that, of all people.

Thanks for your courage.

Love,

Ladies of the future