Behind every food item being sold, there’s a story to tell. In China, where food scares are common, many consumers are particularly anxious to hear it.

With that in mind, a Chinese e-commerce company has made it possible for customers to look at a detailed history of their steaks—from when the cow was born to what it was eating—before it’s served on their dinner tables. The information is being made available with the help of blockchain, a technology known for being hard to tamper with.

JD.com, China’s second-largest e-commerce platform, has been working with Kerchin, an Inner Mongolia-based beef manufacturer, since early May (link in Chinese) to use blockchain to track the production and delivery of frozen beef. People living in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou—China’s most populous cities—can now track the journey of beef ordered from JD.

Food fraud costs the global food industry some $40 billion each year, according to a 2016 report by PwC, but Chinese consumers are particularly fearful about food safety. Their confidence in domestic food products plummeted after tainted milk powder killed six infants in 2008. Today, “exposés” of fake food—not all of which are true—can spread like fire on Chinese social media platforms like WeChat and Weibo, only adding to the confusion and distrust. When problems do arise, the lack of transparency about how food is processed makes it challenging to pinpoint where in the supply chain things went wrong. Instead of being centralized, information is often made available to manufacturers, warehouses, and delivery companies separately.

The life and death of a cow

Blockchain is most frequently associated with bitcoin. To solve one of the fundamental problems of the cryptocurrency—and keep people from “double spending” their digital money—blockchain is used to publicly record every bitcoin transaction. The technology, born in 2008, creates secure copies of a ledger and provides a mechanism for various parties to check and agree on a set of facts, which, after being recorded, can’t be changed. The secure nature of the technology has led to new uses, such as tracking land ownership or tracing the origin of a steak. (The latter use is also being tested, as of early this month, by Golden Gate Meat Company in San Francisco.)

“The information cannot be falsified,” says Josh Gartner, JD’s spokesman. In their partnership, JD will be responsible for the logistics of getting the meat to customers, while Kerchin—which had about $300 million in revenue last year, 10% of it from online sales of beef products—will “ensure the authenticity of all product information,” he adds.

To design and develop its blockchain, JD adapted the architecture from Hyperledger, an open-source project that lets enterprise developers use blockchain technology in various industries.

The process to encode data to blockchain begins with Kerchin scanning barcodes to collect and store data in its own supply chain before providing it to JD, which writes the information to blockchain. After that, any changes require a digital signature, and both parties will immediately be informed of any modifications.

To understand the process, I ordered an eye-round steak, a cut from above the cow’s rear-leg region, from JD on the afternoon of July 14 in Guangzhou. Weighing 200 grams (0.44 lbs), the meat arrived the next day, delivered by a JD courier. Encased in a black box, the front had an opening showing the cut of beef while the back had a QR code and instructions for pulling up information about my food.

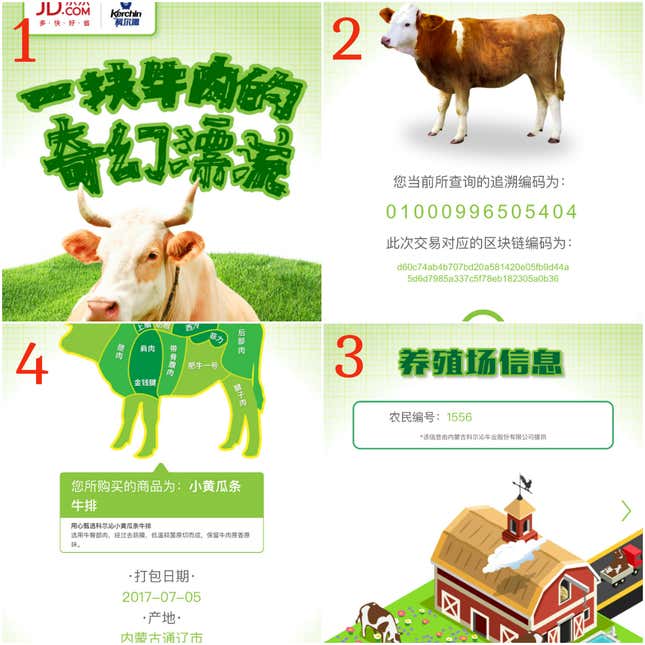

Scanning the code using JD’s app loaded a webpage in the app’s browser titled “The wonderful journey of the beef.” Underneath those words was an image of a cow sitting in a meadow. The next page showed the cow’s serial number and a 64-digit alphanumeric code that refers to the sales transaction.

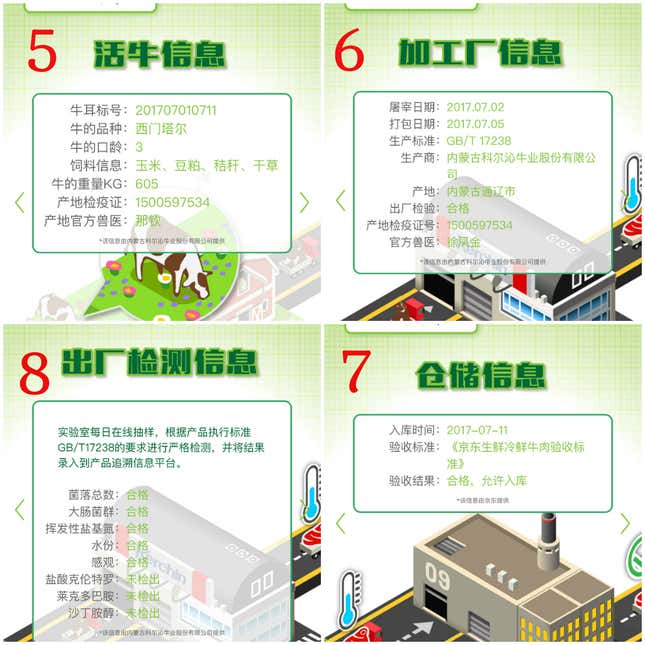

There was plenty to explore. I learned that my cow was three years old, weighed 605 kilograms (1,338 lbs), and was tended to by a local vet named Na Qin before being slaughtered on July 2. A Simmental breed, the cow lived on a farm Kerchin identified as ”1556,” and was fed a diet of corn, wheat, and straw. (The number lets Kerchin track down a farm’s location.)

After the cow was slaughtered, its meat was then subjected to a number of tests to detect bacteria, water content, and animal-growth promoters. At this point, my steak was declared free of ractopamine, a drug banned in China that’s used to bulk up animals (paywall) weeks before they are slaughtered.

While blockchain is hard to tamper with, tracing the origin from calf to chuck steak isn’t foolproof. John Spink, who studies food fraud at Michigan State University, tells Quartz that “fraudsters are very creative and constantly change their methods.” In a 2013 blog post, he wrote that “traceability is not a single magic-bullet to stop fraud, but it is a critical part” to reduce food fraud, adding that bad actors can also operate from within. “In some cases [the] criminals are hiding within the legitimate supply chain so [they] could defeat even a very technologically advanced countermeasure,” Spink says.

JD also admits that there might be lapses in data that’s tracked, depending on “when in the process each party begins to input and share that data,” says Gartner. Because of this, the company will periodically perform spot checks (link in Chinese) at Kerchin’s factories to examine how information is recorded and verify the validity of the data.

In blockchain we trust

Chinese agencies have experimented with other traceability methods in the ongoing fight to restore consumer faith in the food system. The National Platform for Tracking Food Safety, backed by China’s top planning body, has made more than 72.6 million items (link in Chinese) available for supply-chain tracing using barcodes as of Aug. 9. According to a 2015 paper in the peer-review journal BioScience Trends, the implementation of food traceability requires “a substantial amount of valid information.” However, China’s supply chain often involves small factories, and they generally lack dedicated platforms for the exchange of logistics information.

A number of companies besides JD believe blockchain can solve this problem.

Alibaba, China’s largest e-commerce player, announced in March a plan to use blockchain to track beef from Australia, one of China’s key sources of beef, by working with three local companies, including accounting firm PwC Australia.

In October, Walmart also introduced blockchain into its Food Safety Collaboration Center in Beijing. Working with IBM, the retailer recently completed two pilot tests to help move pork from Chinese farms to its stores. The technology has helped reduce the paperwork required to process the containers. Those sorts of transportation documents, such as the bill of lading, can easily be tampered with or copied, making the supply chain vulnerable to criminals who can replace goods with counterfeit products, a type of maritime fraud (paywall) that costs billions of dollars each year.

Starting this September, China will work with the European Union on a project called EU-China-Safe, which will use blockchain and other technologies to regulate food safety. Belfast-based startup Arc-Net, one of the project’s partners, has developed a blockchain platform to support the identification of animal protein from birth, says CEO Kieran Kelly.

It’s possible that scaling up blockchain could allow consumers to track all products back to their source, but that vision is still far away. In the case of Kerchin’s beef, only two parties are involved in gathering and uploading information, but the global supply chain poses more challenges. Cargo often passes rapidly through multiple hands, and parties in supply chains don’t often share data. As the supply chain gets longer, an enormous amount of collaboration and transparency is needed. And of course, not all companies are eager to share their data and business practices.