Some (including us) would argue it’s just about the best week in television.

On July 23, the Discovery Channel launches its 29th annual Shark Week—a week of prime-time programming devoted entirely to the most badass creatures in the deep blue.

Sharks have been brutally vilified by the media. It started with Jaws. The 1975 film “absolutely changed how the world thinks about sharks,” says David Shiffman, a marine biologist at Simon Fraser University, in Vancouver, Canada. The general public became terrified of sharks, despite the reality that sharks—even great whites—are not serial maneaters.

Sharks are actually kind of amazing. Definitionally, sharks (and their close cousins, rays, whose gills are underneath them instead of on their sides) are any fish that don’t have a skeleton. Instead, their bodies are encased in calcified cartilage, which is similar to the tops of your ears, but a bit stiffer. And they replace their teeth almost infinitely because they fall out so easily.

Most fascinating, though, is their ability to detect electrical activity. “They’ve got the most sensitive electromagnetic detection in the world,” says Gavin Naylor, the Director of the Florida Program for Shark Research in Gainesville. Naylor says that if you had a D battery in the Atlantic ocean off the coast of New York, a shark could conceivably detect it all the way off the coast of England (provided there was no other movement in the water, which is impossible—this is a hypothetical). They do so by picking up disturbances in the magnetic field generated by motion (you yourself generate an electric field every time you move) using jelly-filled sensors called ampullae of Lorenzini. These same sensors allow them to find food and navigate through thousands of miles of water.

Sharks are also extremely diverse. “Everybody thinks that these things…haven’t changed in 400 million years,” says Naylor. “But that’s just not true.” He says each species is as different from one another as whales are from bats. Shark habitats range from the deepest depths of the ocean to the surface; some prefer freshwater rivers to the salty seas. Some eat plants instead of animals; some of them are pink.

Shiffman hopes more people will see sharks for what they actually are: Apex predators dutifully keeping the marine food web in balance. They need to be protected; without them, prey would run rampant throughout the ocean, destabilizing ecosystems.

Although conservation does mean more sharks in ocean waters, that doesn’t mean more humans will be killed by sharks. Although there have been more attacks in recent years, far fewer of them have been fatal (likely thanks to modern medicine). And even with the recent uptick, shark attacks are still so incredibly rare that many of us have probably unknowingly swum with sharks in the past. “If you’ve been in the water in the coastal US, there’s been a shark near you,” Shiffman says. These sharks have almost definitely been aware of you, too, and just decided not to bat a fin at you.

And conservation has its upside. Shiffman hopes more sharks in the waters can mean more opportunities to study them. At the moment, most studies are done by looking at sharks when they come to the surface, or visiting them underwater for brief stints at a time, which would be like studying a bee only when it lands on a specific flower or for a few minutes at a time. Being able to better study sharks isn’t just good for them; it’s potentially beneficial to us humans: Because sharks live in so many different places, Naylor thinks they’re exceptionally good at adapting to their surroundings—which could mean their genomes will bring us advances in modern medicine adaptable.

In order to honor these majestic kings and queens of the sea, we at Quartz decided to profile our favorite sharks, using information available from the Florida Museum of Natural History’s fish and shark species profiles. These are just a select few of the 500 species swimming out there.

We’ll also be tweeting all week at @weratesharks, with a hat tip to Matt Nelson, who runs the We Rate Dogs twitter account.

Great white shark

Carcharodon carcharias

Weighing in at 1,500-2,400 lbs (680-1088 kg), is the champion of sharks: the great white. These apex predators enjoy a spot at the top of the food chain (although killer whales have been known to hunt them on occasion). They live in any temperate waters, which means they can spend time all over the world—except in the Indian ocean and along the coast of Antarctica.

Contrary to the bad press they’ve gotten, great white sharks don’t actually hunt humans; they’d much prefer something fattier, like a seal. But they’re also curious creatures, and tend to take a bite out of anything they see, just to see if it’s tasty. Usually they’ll come at a potential meal from the side, but occasionally do “surface charges” where they sprint to the surface of the water and bite prey with a big swimming jump. They also like to break the surface and splash down, like whales, to send a threatening message to other great whites in the area who may be competing with them.

Tiger shark

Galeocerdo cuvier

These sharks can grow up to 1,600 lbs and enjoy a range in tropical ocean waters (warmer than 18°C, or 64.4°F). Their stripes are actually collections of spots that run together as the shark reaches maturity. Tiger sharks will eat almost anything (one was once found with two burlap sacks in its stomach), and are one of the few shark species that give birth to live young after the eggs hatch inside the mother.

Bull shark

Carcharhinus leucas

Although smaller than other sharks (they max out at around 290 lbs), bulls are considered the most dangerous of species—bull shark attacks on humans swimming on the Jersey Shore were the inspiration for the film Jaws. Unlike most other species, bull sharks can swim in salty, brackish, and even fresh water (one was found over 2,000 miles up the Amazon River)—though they do prefer shallow water, They eat a variety of fish, rays, and turtles, and have even been known to eat other young bull sharks still in nurseries.

Great hammerhead shark

Sphyrna mokarran

There are actually nine different types of hammerhead sharks; great hammerheads are coastal sharks that live in tropical waters, and migrate to colder areas for the winter. Their young have more rounded heads than other hammerheads, which become rectangular and larger as they mature. Great hammerheads have been known to occasionally attack humans, but we tend to kill many more of them than they do us through overfishing for their liver oil used in vitamins and fishmeal; they’re classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Cookiecutter shark

Isistius brasiliensis

These sharks aren’t more than a few feet long, and live deep in the ocean—3,000 ft below the surface, in tiny pockets of tropical waters all around the world (as far as we know). There’s no record of cookiecutter sharks ever hurting a humans, but they do have a particularly grisly way of killing their prey, which include seals, whales, and other fish: they latch onto their dinner, and spin their bodies around to make a perfectly circular bite mark, similar to lampreys.

Whale shark

Rhincodon typus

This big boy wins the award for largest fish, clocking in at more than 40 ft long and weighing up to 50,000 lbs. Whale sharks, though, are fairly docile, and eat mostly plankton and other tiny fish that come into their mouths when they swim by with a big gulp. Whale-shark meat is eaten by humans in parts of Taiwan and the Philippines, and fishermen like to see them because their presence usually indicates lots of plankton and tuna nearby.

Lemon shark

Negaprion brevirostris

Lemon sharks are light brown (sorta edging towards almost a lemony-yellow), grow 8-10 ft long, and live in shallow waters along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the US and South America, and off of western Africa. These sharks are especially social: they tend to live in pods, and have even been shown to learn (paywall) from one another. They give birth to live babies, and eat mostly small fish in coral reefs.

Goblin shark

Mitsukurina owstoni

These may be the strangest sharks to roam the seven seas. They are rare and live anywhere between 300 and 4,000 ft below the ocean surface. Recently, scientists from Japan found that they hunt by throwing out their lower jaws at speeds up to nine feet per second in a move called “slingshot feeding” (paywall). Luckily, they mostly eat octopus and other creatures living at the bottom of the ocean—so no need for surfers and sunbathers to worry.

Tasselled wobbegong

Eucrossorhinus dasypogon

The untrained eye may miss the tasselled wobbegong—and that’s the secret to this shark’s evolutionary success. They live in coral reefs off the northern coast of Australia, grow to be four feet long, and hunt by camouflaging themselves, waiting patiently, and then springing out of the shadows. The only danger the tasselled wobbegong poses to humans is if the shark mistakes dangling feet for its favorite meals: squidfish and soldierfish. Luckily for us people, these sharks tend to eat only at night.

Greenland shark

Somniosus microcephalus

Greenland sharks like only the coldest water. In the winter, they enjoy swimming in the shallows of polar waters (less than 10°C, or 50°F), and in the summer dive down to up to 3,000 feet—presumably to keep cool. These dark-grey or brown sharks can grow up to 24 feet long and eat other deep sea fish, like lumpfish (hungry yet?)—although reportedly have been found with reindeer and horse in their stomachs. Back in 1859, fisherman said they found a human leg in one, although this was never proven. They are the longest-living vertebrates known on Earth; one even celebrated her 400th birthday in Aug. 2016.

Nurse shark

Ginglymostoma cirratum

These coral-reef-dwelling sharks live only off the coasts of Central and South America and east Africa. They’re bottom and nighttime feeders, and typically eat crabs, mollusks, and rays. Sometimes, they’re referred to as “cat sharks” because of the whisker-like nasal barbels (external taste buds used for finding food) on their faces. They’re creatures of habit; they like to frequent the same caves over and over again.

Whitetip reef shark

Triaenodon obesus

These sharks typically spend their time off the coast of east Africa and in the Indian and Pacific oceans. They’re named for their white-tipped dorsal fin. They’re sometimes hunted by humans for food, and are considered to have an “easygoing disposition” by the folks at the Florida Natural History Museum (although reportedly they will bite “if harassed”). They enjoy spending time in caves, and like to eat octopus.

Shortfin mako shark

Isurus oxyrinchus

The shortfin mako can grow up to 12 ft long, and is the fastest-swimming shark in the ocean: The Shark Research Center’s Naylor says that makos have been recorded at 60 kilometers per hour (about 37 mph), others suggest that they can reach 60 miles per hour. And, they also can jump out of the water. They eat just about everything in the ocean—including smaller shortfin makos. They usually swim in tropical or temperate waters all over the world (from Norway to South Africa, according to the Florida Natural History Museum), but can also survive in colder waters typically found around the poles. They are one of five species of sharks that can regulate their own body temperatures (the others are the longfin mako, the white shark, the salmon shark, and the porbeagle).

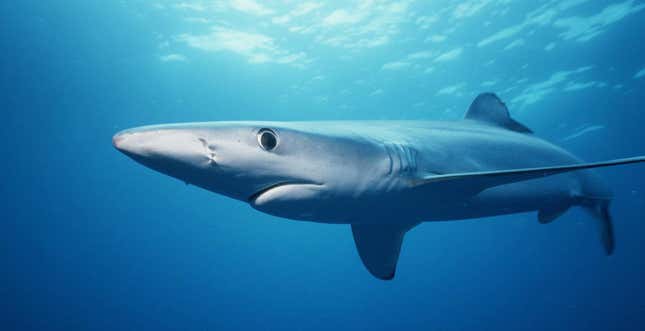

Blue shark

Prionace glauca

Blue sharks are named for their blue-grey skin, and live pretty much all over the ocean except for Arctic waters. They also stick to fairly shallow waters, not going below 1,000 ft or so. They usually eat invertebrates like squid and octopuses, and don’t typically attack humans, but won’t not attack humans if there’s a chance for them to get food. They can be up to 12 feet long, and people accidentally catch them when fishing fairly regularly. Fun fact: blue shark moms can have litters as large as 100 pups, which are some of the largest litters among sharks.

Megalodon

This giant monster died out 2 million years ago. Sad to see it go, but it was also basically a 50-foot-long white shark with seven-inch teeth in a jaw that opened up into a 9 x 11 ft jaw.

Basking shark

Cetorhinus maximus

These are the second-largest fish in the sea, reaching 40 ft in length, and like the biggest—the whale shark—basking sharks are filter feeders. In the summer, they skim the surface waters along temperate (10°C to 18 °C, or 50°F to 64.4°F) coasts with their mouths open to feed on plankton (filtering 2,000 tons of water per hour). They’re no real threat to humans, but we’ve hunted them extensively for their meat, oil, and livers, and the IUCN currently classifies them as “vulnerable.”

Left Shark

This isn’t a shark, but is actually just a human dancer in a shark costume who appeared onstage while Katy Perry performed her song “Teenage Dream” at the 2015 Superbowl. Left Shark became a pretty popular character on the internet after the performance in which he (she?) proved to be much less coordinated than dancing partner Right Shark.

Glass shark

This is also not a real shark. This shark is a figment of your imagination (explained here on an advice show for the modern era) that sometimes seems to appear when you’re in a swimming pool. There are no sharks in swimming pools; they would die in the chlorine.

Make sure to follow @weratesharks all Shark Week for our shark rates. They’re good sharks, Brent!