The San Francisco Bay Area, one of the United States’s steadfast liberal bastions, recently saw its BART train system, the 5th busiest in America and vital connection across the bay, go on strike for a week. In the same week, the news broke that CEOs in the United States now make 273 times the average salary, by the far the highest ratio in the developed world.

Paradoxically, it was the BART workers, averaging $72,000 a year in base salary, and not millionaire CEOs, who were most vilified, even in San Francisco. Poll after poll showed area residents firmly on the side of BART management, while online message boards and Twitter were flooded with comments calling union members “greedy” for expecting a pay raise—4% a year for the next four years, after getting nothing the past five years—and for having the nerve to expect their generous—health care and pension benefits to be maintained.

https://twitter.com/LilacSundayBlog/status/351668412101042176

When the general public is firmly against a union, even in the liberal Bay area, which hasn’t seen a pay raise in five years, and a strike isn’t a rallying call for a larger economic battle, it is clear that the relationship between workers and the general public is broken.

The race to the bottom

Not surprisingly, the US economic recovery shows the same disconnect. While the stock market hits record levels, average worker wages remain flat. While CEO salaries rise, the full-time workforce rate drops. Union jobs stand out for being the last bastion of well-paying, full benefits jobs. And they are in decline.

Across America, workers are struggling with rising costs and wages that just won’t keep up, and the Bay Area, one of the most expensive regions in the country, is no exception. The front lines are set, though. BART workers don’t deserve higher wages because so many others don’t get those benefits. If we can’t have them, no one can. The lowest-common denominator has become, amazingly, the best that BART workers can expect.

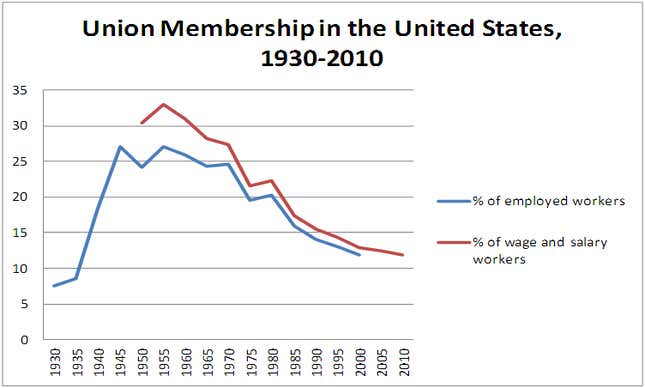

The balance of power has shifted since 1965, when CEOs only made twenty times the average salary and when union membership was 27% of the salaried workforce. It has been dropping steadily—to 11.3% today—while corporate power has grown. Today, rulings like Citizens United—that created Super PACs that raise unlimited, undisclosed funding from corporations and individuals—and the increased the access that business leaders and lobbyists have in government, have only strengthened their hand. Unlike 40 years ago, the stalwarts of the American economy—Google, Facebook, Wal-Mart, Exxon-Mobil, Apple—are all non-union. Three of those companies are based in the Bay Area, and are responsible for increased rent costs, tied to growing numbers of highly paid staff coming in and sucking up the most desirable housing.

Those rising costs are hitting BART workers, who, adjusting for inflation, took a near 12% pay cut since the economic crisis in 2008. While Mark Zuckerberg and Larry Page get increasingly massive compensation packages, BART management’s offer to the union would negate any pay increase with increased pension and health care contributions. It would mean a decade of, essentially, stagnant wages while the Bay Area’s cost of living grows faster than the national average. That, in today’s economic landscape, is greedy. It is also, sadly, the norm.

The flip side

While the US has yet to recover the jobs lost during the 2008 recession, CEO salaries, which took a major dip, have risen by an astounding 54% over the past three years, while average wages have remained stagnant. The glut of workers is allowing those in most industries to keep wages low, aided by government inaction and a minimum wage that peaked in value in 1968, with a purchasing power of $10.70 (pdf).

This is the battle we saw when union supporters protested outside the Wisconsin State Capital in 2011, and in the one-day, nationwide strike held in various big cities throughout this year. One side wants to weaken union power, while the other side is fighting for quality jobs and for better, living wages. The lines are drawn.

The trains are running again in San Francisco, but that’s doesn’t mean the battle is over. The two sides only agreed on a 30 day respite, and negotiations are ongoing to reach a new deal. The public relations battle is heating up too. Recently, BART General Manager Grace Crunican has been going around station handing out free Clipper cards, while union members posted fliers on all the trains with their own message of “Building a Better BART.” This, more so than the eventual contract details, is what will really matter, because as long as the public distrusts unions and ignores rising income disparity, reality will follow a new version of the age-old saying. The rich will get richer, and the poor will be seen as the greedy ones.