When it comes to investing in China, buying the indexes is a bad idea

China’s Q2 GDP growth came in at 7.5%—which is lousy for China, but really impressive in the context of other countries. But just who is benefiting from China’s outsize GDP growth? Not foreign investors, apparently.

China’s Q2 GDP growth came in at 7.5%—which is lousy for China, but really impressive in the context of other countries. But just who is benefiting from China’s outsize GDP growth? Not foreign investors, apparently.

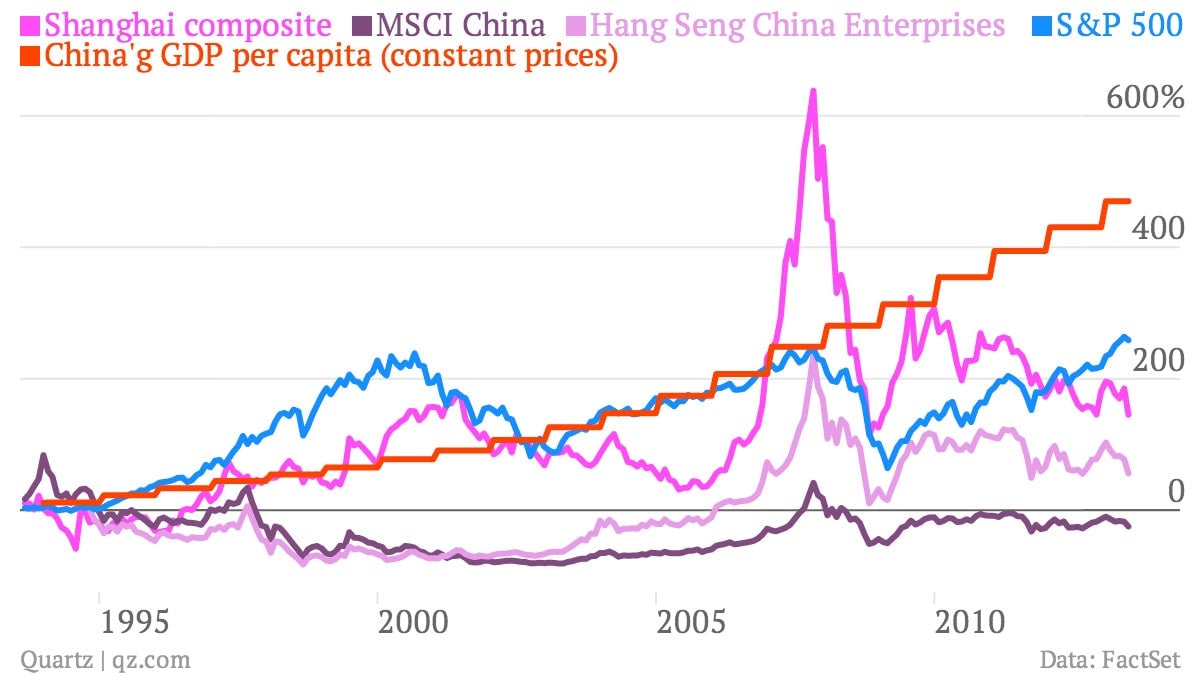

Over the past 20 years, the MSCI China Index—the first index to allow a broad base of foreign investors to buy into the Chinese stock market—has performed dismally compared with the S&P 500 index, as Bloomberg points out. The Hang Seng China Enterprises Index, which tracks Chinese stocks listed on the Hong Kong Exchange and is another avenue for foreigners to invest in China, has also performed poorly.

The discrepancy between China’s GDP and the performance of its stock indexes reflects the imperfection of GDP as a measure of economic prosperity. GDP measures economic activity, but it doesn’t factor in the longer-term value generated by that activity. Accordingly, China’s investment-led economic model has been engineered to create outsize GDP growth, without much concern for value, which explains its ongoing debt crisis.

Stock performance, on the other hand, generally depends in some part on profit potential.

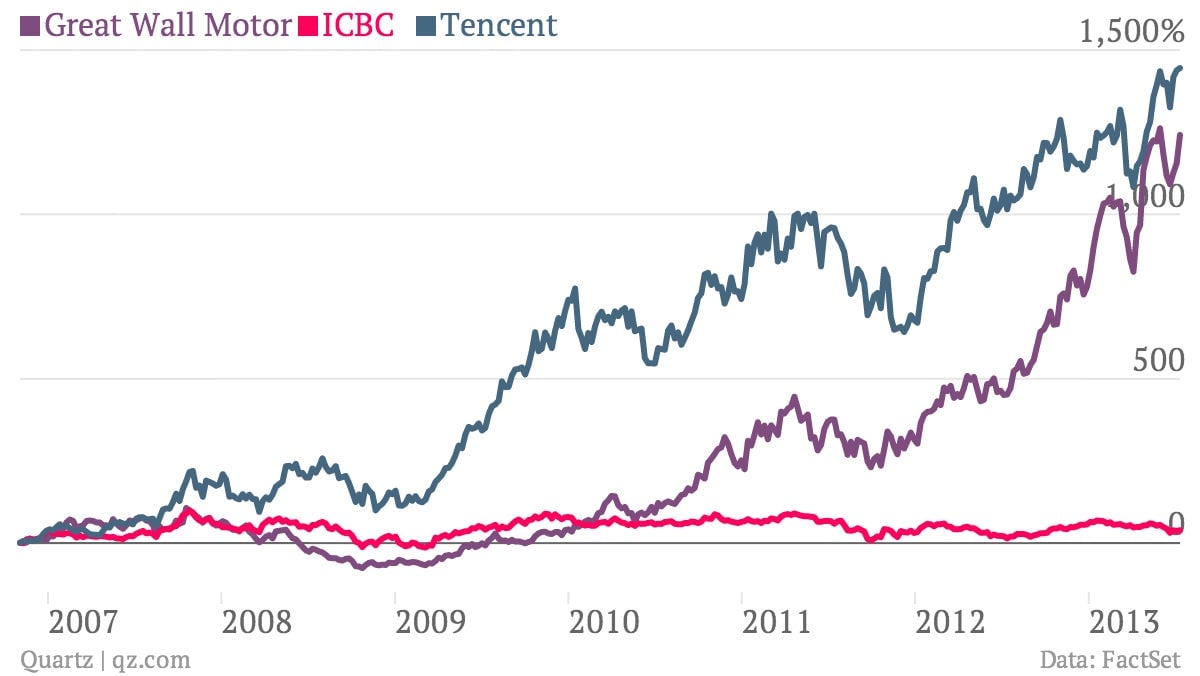

Both the MSCI China Index (pdf) and the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index (pdf) are weighted heavily toward financials, industrials and energy companies—sectors dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs). China launched stock exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen, and later listed SOEs on the Hong Kong exchange, partly to recapitalize them after years of mismanagement.

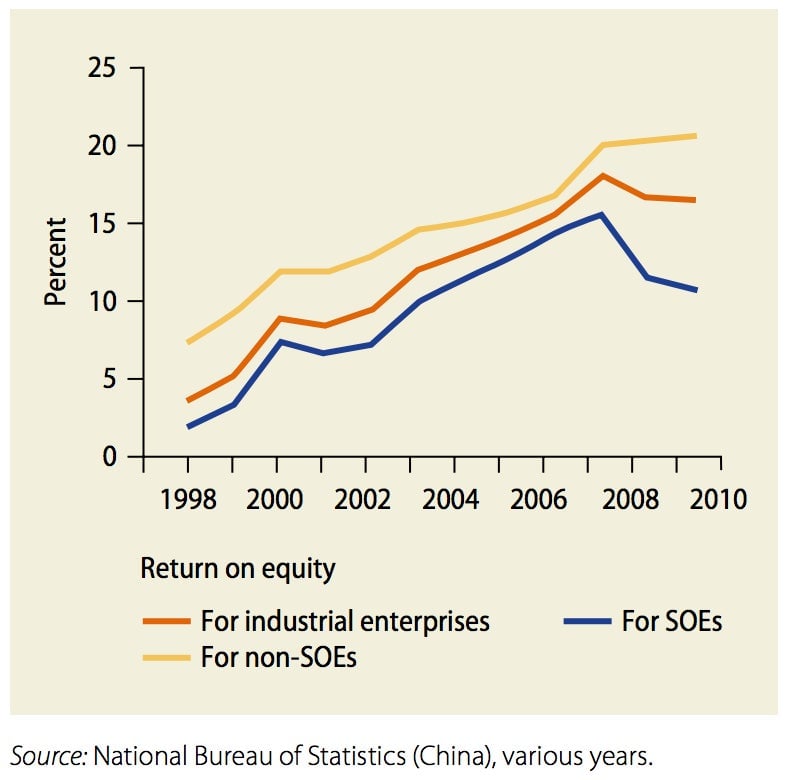

SOEs might seem compelling given that they enjoy state monopolies and oligopolies. But the proceeds of those are also often used to pay back their majority shareholder—i.e. the Chinese government. Also, as instruments of state policy, profitability is at times a secondary concern.

All of these factors contribute to the steady outperformance of private companies versus SOEs. Here’s a look at that, via the World Bank (pdf):

However, companies that cater toward the Chinese consumer, which represent just under 11% of the MSCI and 6% of the HSCE index, tend to be a much more profitable, and they’re better performers than SOEs. Compare, for instance, digital powerhouse Tencent, non-state-owned automaker Great Wall Motor and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, which is two-thirds owned by the Ministry of Finance:

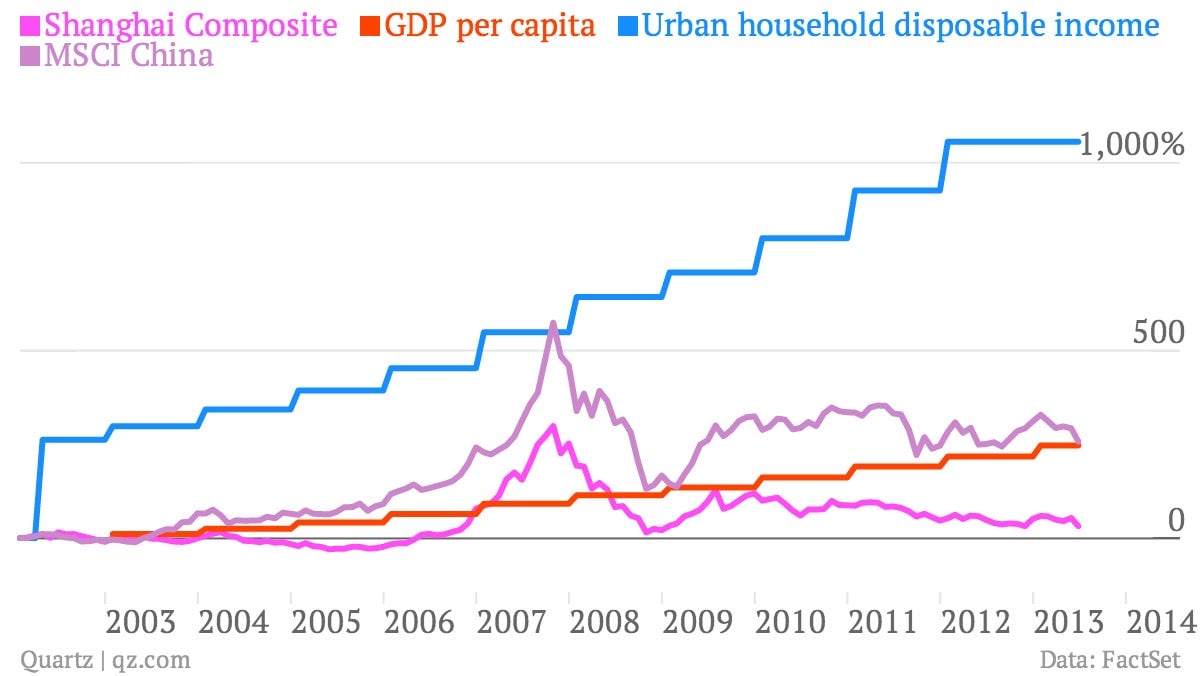

The good news: even if foreign investors in China-focused index funds haven’t benefited from China’s GDP growth, its populace has. Take a look at the growth of urban household disposable income:

Consumption only contributed around 45% of GDP growth in the first half of 2013, compared with the previous year. That means a lot of the growing household income is going toward savings. If the government can successfully shift away from state-led growth and toward an economy powered by consumption—the chief objective of much-discussed “structural reform“—the divergence between dynamic private-sector companies and clunky SOEs will widen further.