Nairobi

Days before Kenya holds a high-stakes general election, its capital city has become a ghost town as residents head to their ancestral rural areas to vote or to avoid any potential violence. The city’s traditionally clogged streets are quiet. Grocery store aisles sit empty, their stocks cleared out by families stocking up in case instability renders them homebound.

Some foreigners have left the country for a while—the United States has issued travel warnings for Kenya for the election period and other countries have cautioned their citizens to take extra care during the election.

“It is only prudent to get out,” says Asad Hussein, a Somali refugee who was born in Kenya and studies at a local private university in Nairobi. He is going back to stay with his family in the Dadaab refugee camp in northeastern Kenya.

The Aug. 8 polls, the country’s most expensive presidential election in history, comes a decade after disputed results of an election in 2007 pitched the country into chaos. At least 1,100 people were killed and about 600,000 displaced, plunging the East African economic powerhouse into uncertainty. The country’s last election in 2013 was peaceful, but locals and observers worry this time won’t be the same.

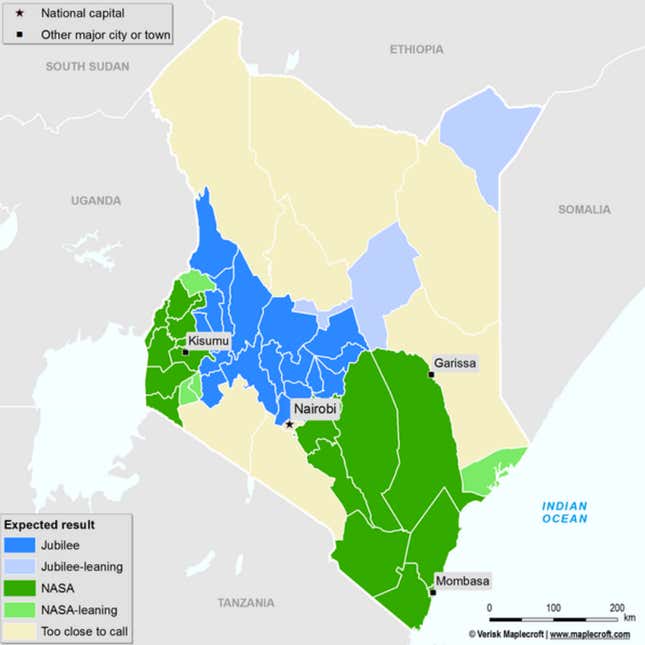

Local media and officials are not as focused as they were in 2013 on promoting peace. Observers also say that public confidence in Kenya’s electoral commission and the judiciary, which would mediate any dispute, are both low. Most significantly, the race is close. As recently as May, incumbent president Uhuru Kenyatta was expected to win a second, five-year term handily. Now different polls show him and his rival, opposition leader Raila Odinga, closing in on each other with the possibility of a run-off.

Almost every step of this campaign season has been fraught. Protests have been volatile and even fatal. On July 31, just eight days before polling starts, Chris Msando, the senior electoral official in charge of managing the IT systems of the voting technology, was found dead in Kikuyu town outside of Nairobi with one of his arms cut off. A man armed with a machete also attacked the home of deputy president William Ruto. Fake news has also become a mainstay of the election, with Facebook and WhatsApp driving the spread of attack ads, propaganda stories, and misinformation.

“The potential for a contested outcome to the presidential election in 2017 resulting in inter-communal conflict or violent street protests remains high,” says Murithi Mutiga, senior Horn of Africa analyst for International Crisis Group.

It’s not just the presidential election that is cause for concern. On Tuesday, Kenya’s 19.6 million registered voters (pdf) will also vote for the over 14,000 aspirants vying for legislative, gubernatorial, and regional county representatives. Kenya adopted a new constitution in 2010, devolving more power to governors and county assemblies, making those elections as hotly contested as the presidential race.

Tough times

President Kenyatta is pinning his re-election hopes on promising to create 1.3 million jobs yearly, rolling out free secondary school education from January 2018, providing free medical care to anyone aged over 70 years, expanding the country’s infrastructure, and enhancing agricultural production.

Despite some successes, his administration has been stained by industrial strikes and widespread corruption. Equally, his government went on a borrowing spree to ramp-up electricity production, build ports, roads, bridges and the new Chinese-built railway from Mombasa to Nairobi. The massive investment in infrastructure has supported an economic growth of over 5% since 2013, but the benefits haven’t trickled down to the ordinary folk.

“The man on the street has found themselves worse off rather than better off. This is a conundrum the incumbent party is rowing against,” says Aly Khan Satchu, a Nairobi-based financial analyst.

Odinga, on the other hand, is promising to fight endemic graft, ensure a food secure nation, uphold the rule of law and press freedom, provide universal healthcare, eradicate poverty, and rein in growing public debt currently at over $41 billion (53% of GDP). In June 2013, the country’s gross public debt stood at $18.9 billion.

In recent months, the country has faced a drought that pushed up food prices and further escalating criticisms against the government. Like elsewhere in Africa, high levels of youth unemployment amid a growing population is a ticking time-bomb in Kenya. Kenyatta’s administration, for instance, promised to create one million jobs annually since 2013, but this hasn’t been the case. This hallmark pledge of job creation got millions of young people streaming into polling stations in March 2013 to vote. But, as it turns out, thousands of employees have lost their jobs at multiple companies, citing a difficult operating environment.

At major bus stations in Nairobi, Quartz spotted throngs of people boarding buses heading to western Kenya. Many of the travelers could not be deterred by the fact that fares had doubled on the routes they were traveling as long as they reached their rural homes safely. Flora Sindoli, a micro-business owner, says she was traveling to her hometown of Vihiga county in western Kenya because that was where she felt safe.

“In case the election is contested or is not free and fair, it could turn out like 2007 and I don’t want to be caught off guard,” she said.

Uncertain outcome

Despite what happens, the government says it has marshaled 180,000 personnel from various security agencies to man the elections and to forestall any related violence. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission has also said it is monitoring hate speech on social media outlets. Kenyan crowd-mapping start-up Ushahidi, which started in the aftermath of the 2007 election, has opened a platform for tracking incidents of violence or electoral violations.

But a seamless enforcement of law and order might be easier said than done. On Thursday (Aug. 3), Odinga told Reuters that the only way the ruling party can win the election was by rigging the results. And it’s rhetoric like Odinga’s that is making many people brace for an uncertain outcome.

“It’s like preparing for the big unknown: you just don’t know what is going to happen,” says Henk Hoff, an information management coordinator with an international NGO in Nairobi. Hoff says that he has planned to be out of the country during the time the results will be announced. “We all hope for peaceful elections.”

*Additional reporting by Lily Kuo