Is China’s economy actually growing by 7.5%? No, not really.

There’s a fun game that happens at the beginning of each quarter: figuring out what China’s GDP growth really is. Let’s kick off a round of that with what China’s GDP growth rate would look like if it used the international standard for measuring its growth.

There’s a fun game that happens at the beginning of each quarter: figuring out what China’s GDP growth really is. Let’s kick off a round of that with what China’s GDP growth rate would look like if it used the international standard for measuring its growth.

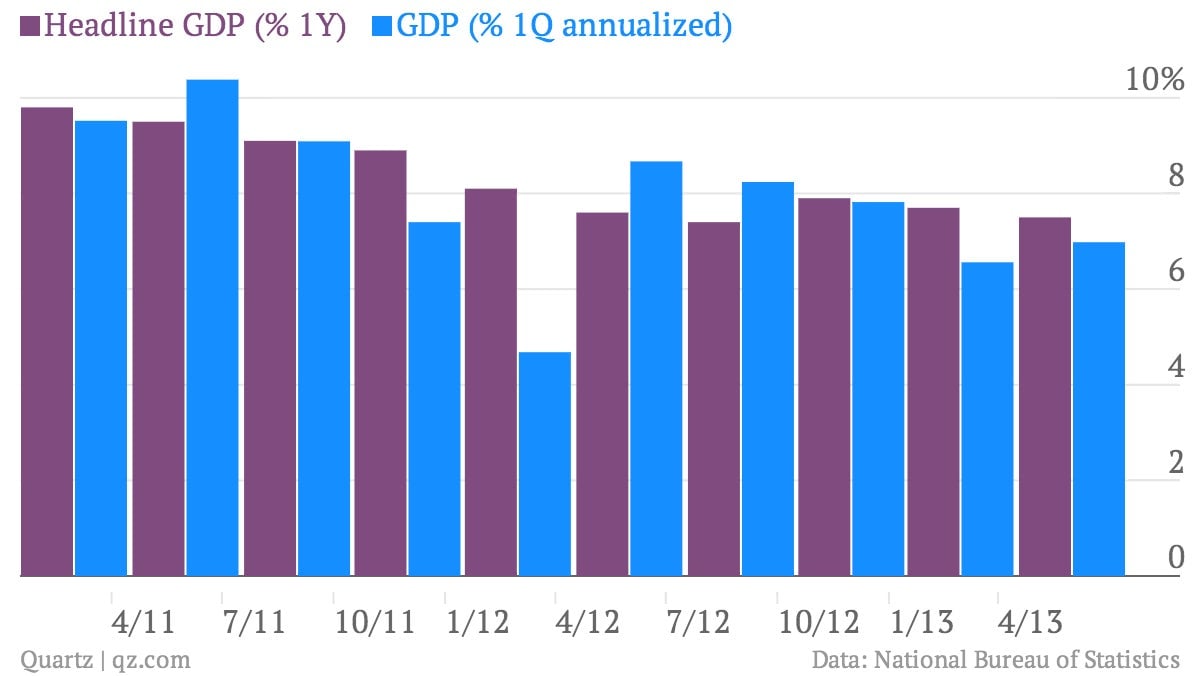

The 7.5% growth China reported on Monday compares output from Q2 2013 with that of Q2 2012. But most major world economies do it differently. The method used for, say, the US’s Q1 GDP of 1.6% measures Q2 output against Q1, adjusting for seasonal factors and annualizing it (meaning, projecting what annual growth would be if the economy kept growing at the Q2 rate). This approach captures momentum more quickly than the year-over-year method China uses.

Measured by international standards, China’s GDP growth rate is actually much lower than 7.5%. It’s just shy of 7%, in fact:

Also of note: growth picked up in Q2, compared with Q1, according to China. But it fell by the year-over-year measures—from 7.7% in Q1 to 7.5% in Q2. What accounts for the discrepancy between China’s quarterly and annual data trends?

Unfortunately, the government doesn’t offer any explanations with its data. It’s possible, though, that the Q2 surge in investments like infrastructure and property boosted economic output compared with Q1’s investments, at the same time as the overall economic slowdown—and possibly a slowdown in consumption—offset that uptick in year-over-year measures.

That interpretation takes government data at face value. But many prefer not to. Société Générale’s Wei Yao is skeptical of the convenient surge in recent investment, as FT Alphaville highlights. That spike offset a fall in net exports (though not in the size of the trade surplus itself).

She also highlighted the fact that the government’s inflation calculations were oddly low. If Yao is right, it means the government recorded gains to the GDP that came simply from rising prices, and not actual increases in output.

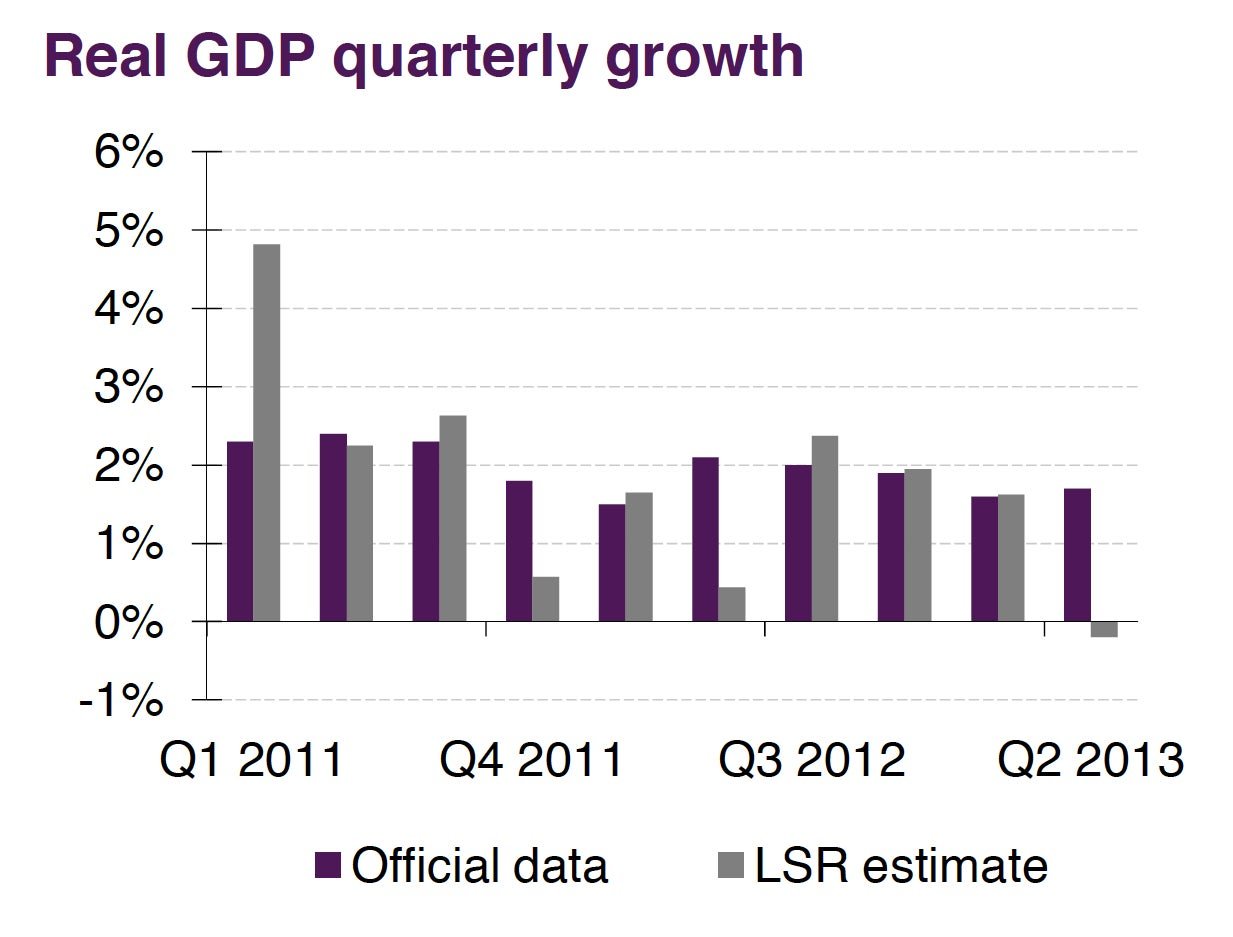

A much darker reading still comes from Lombard Street Research’s Diana Choyleva. Not only does she dismiss the government’s estimates, but her calculations showed China’s GDP actually contracting in Q2, compared with Q1. Here’s a look at LRS’s GDP projections versus the seasonally adjusted data that the Chinese government releases:

Like SocGen’s Yao, LRS also finds the government’s inflation measures to be dubious. As a result, it calculates real GDP based on its own price data.

As for the future: “Weak external demand, an overvalued yuan, decimated corporate profits and high real interest rates could well push the economy into a technical recession in Q3,” writes Choyleva. In other words, the real pain has yet to come.