Even when they’re profitable every day, high-frequency traders aren’t making much money

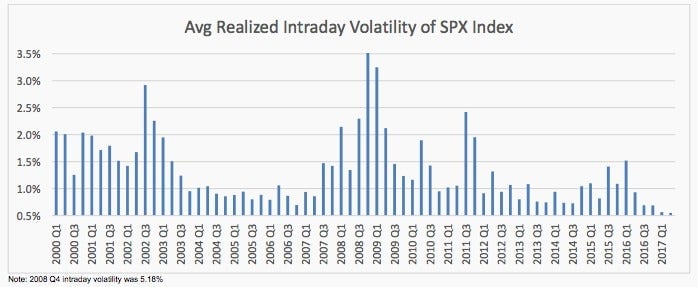

Virtu Financial—one of the world’s largest computerized trading firms—made money every trading day last quarter. The problem is that it made less of it than in the past, as volatility in the financial markets has dried up in recent months. Big price swings are good for high-frequency trading strategies, as machines can swoop in and take advantage of market shifts.

Virtu Financial—one of the world’s largest computerized trading firms—made money every trading day last quarter. The problem is that it made less of it than in the past, as volatility in the financial markets has dried up in recent months. Big price swings are good for high-frequency trading strategies, as machines can swoop in and take advantage of market shifts.

While many high-frequency trading shops are secretive about their results and plans, Virtu is listed in New York, so its required updates provide a view into the state of the industry. The company’s profit from trading fell in just about every category last quarter, with net income from currencies and commodities taking the biggest hit, each declining some 30% versus the same quarter last year. The company’s share price fell by 8% in early trading.

Other big financial firms have also suffered from the drop in volatility, as placid, calm markets often mean fewer opportunities to make money. Goldman Sachs has faced a barrage of scrutiny as its commodities unit sputters.

That’s not the entire story, however, as there are signs that it is becoming harder to make money in computerized buying and selling these days. High-frequency trading has become far more competitive, so there’s less profit to go around. The cost of gaining an advantage—from blazing fast machines to top-tier coders—is also going up, eating into earnings.

An analyst on Virtu’s earnings conference call today asked whether its business model is somehow broken. CEO Doug Cifu said such speculation just shows that many people don’t understand high-frequency trading.

Cifu said Virtu hasn’t traditionally relied on quantitative models to predict market moves, which means it doesn’t have to worry about its mathematical models becoming less effective. He said there will always be a need for market makers—firms that post bids and offers—because buyers and sellers don’t “mystically” meet up to consummate transactions. The market needs an intermediary to make it happen. When volatility declines, the gap between bids and offers also shrinks, making it harder for firms like his to make money.

When an industry becomes more competitive, one strategy to squeeze out more profit is to go for scale. That’s likely why Virtu bought another big trader, KCG, for about $1.4 billion earlier this year. The combined group is so big that if you buy or sell a US stock, there’s about a one-in-five chance (paywall) that Virtu will be on the other side of the transaction.

With profits under pressure, the company is also aggressively cutting costs: KCG’s headcount was 923 full-time employees in March, while in December Virtu had just 148. Since the merger, as one analyst said during the conference call, Virtu already “took out a lot of heads.”