As a media reporter, I find myself struggling with what to call TV and film today. In the 1990s, it was easy. Things on TV were TV shows. Things in the cinema were movies. Now, more people than ever are making what we continue to call “TV shows,” but no one is watching them on television screens.

In August, before the usual fall US TV season kick off, Facebook launched its own lineup of original video series rivaling those from traditional TV channels. Snapchat released a similar stock of shows earlier this year, including a handful of offshoots of existing TV series, but all of which are only available via its mobile app. Netflix and Hulu—that latter of which just snagged the first best-series Emmy for a streaming service—have proved they can make dramas and comedies as good as any TV network out there.

Meanwhile, movies in cinemas, like the Fast and Furious franchise, are being told over five, six, 10 installments—like stories are told in TV. Episodes of shows like Game of Thrones are regularly the length of feature films. Darren Aronofsky designs his films to look good on an iPhone.

Had Netflix’s Stranger Things, which returns for its second season this month, been made in another era, it probably would have been a movie. That’s how the Duffer brothers envisioned it. But “nobody wanted to hear movie ideas,” said Matt Duffer recently. ”They wanted to hear television ideas.” So, he and his brother, Ross, turned their homage to Eighties pop culture into a movie for the small screen—told in eight parts.

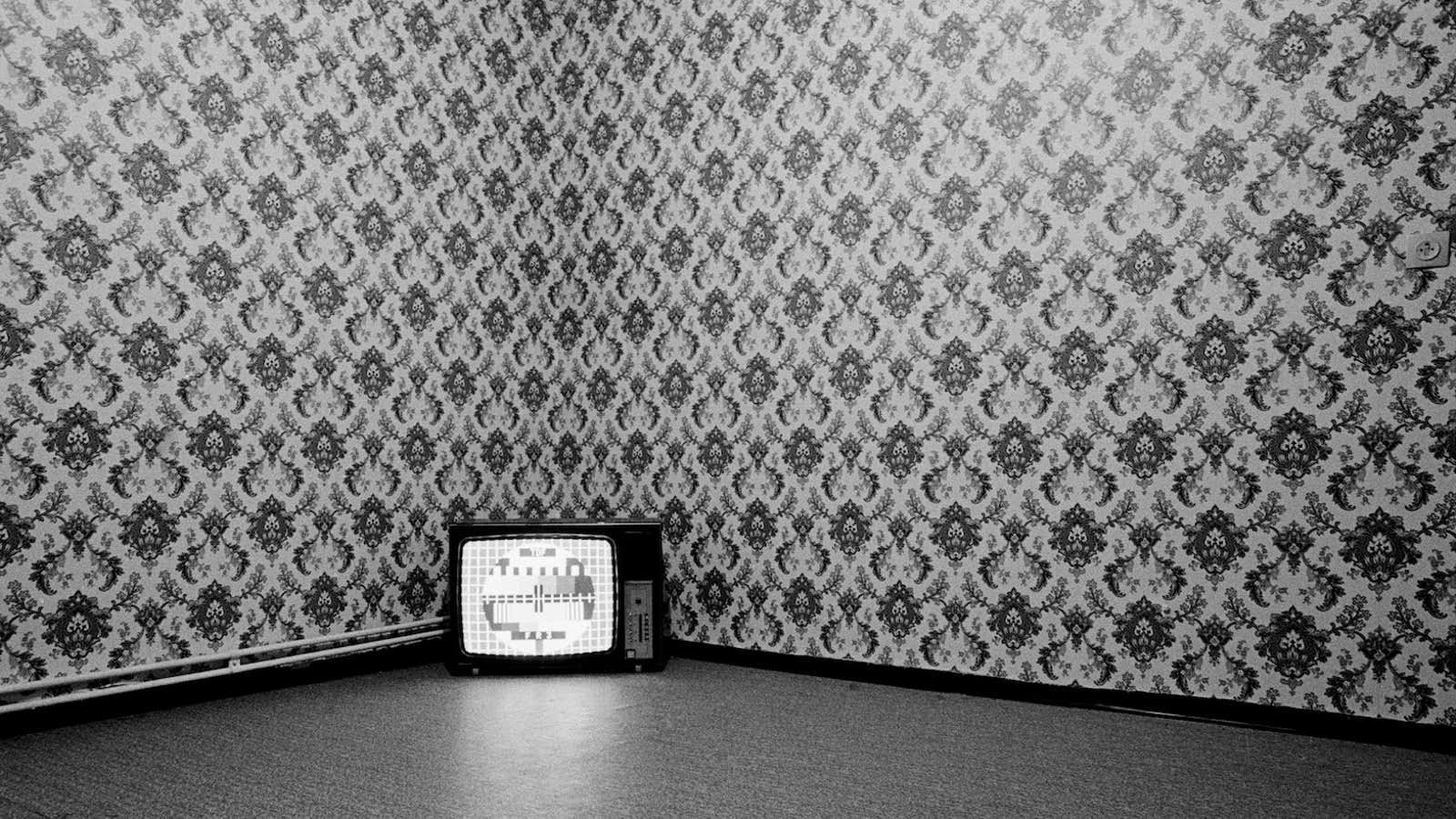

None of this is TV in the standard sense. It comes as TV sets are disappearing from American homes, and more media is being consumed (pdf) through a combination of other devices including smartphones, tablets, desktop computers, game consoles, and multimedia devices like Rokus, radio, and DVD and Blu-ray players. Almost everything can be watched through one glass screen or another.

But if it looks like TV and sounds like TV, why isn’t it? It’s a question I ask myself daily. It’s my job to describe TV, streaming, and other programming to readers. If I don’t know what to call this stuff, does anybody?

From video to video

This isn’t the first time this issue has come up. The language around video storytelling has always been steeped in format and distribution.

In the late 1800s, when we learned how to record and show still images so that the objects in the images appeared to be moving, we called the byproducts “motion pictures” or “moving pictures,” and later, “movies,” according to the Online Etymology Dictionary. The images were recorded on “film,” which became another moniker. And the films were shown in “cinemas,” stemming from the French word for ”motion-picture projector and camera.”

The word “television” was coined in the early 1900s in reference to a theory that moving pictures could be transmitted over distances, which is what the technology became known as when it was developed in the 1920s and 1930s—as did the medium. And the term “video” was first used in back the 1930s to mean “that which is displayed on a screen,” especially a TV screen. It calls back to the Latin video, meaning “I see.”

Nearly 100 years later, we’re still using the same words. But what do we call TV and film when it’s no longer watched on TV sets or shot on film, respectively? How do we refer to a story that’s made like a movie, structured like a TV show, but released online? Do creators see a difference?

“TV, for the audience, is when you watch it on your TV [set],” said YouTube creator Andy Signore, who recently adapted his online series Man at Arms for the TV network El Rey. “A TV show is a larger-scale production distributed to a pre-existing audience,” said another YouTuber, Hannah Hart, when comparing her YouTube series to her The Food Network TV show I Hart Food.

Digital is “short-form stuff,” while TV is longer-form, said Bill Rouhana, CEO of Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment, which produces programming for TV networks like A&E and CBS, as well as online outlets like its subsidiary, APlus.com, founded by actor Ashton Kutcher.

When Hart, one the YouTubers, posted her first video on the platform back in 2011, strangers who watched wrote in the comments that it was their favorite new “show.” She had no idea there were shows on YouTube. Now, “I don’t know anyone of my peers who says, ‘I’m looking for new digital series to watch,'” said Signore, the other YouTuber. “The term is just show. It’s a show. It’s a movie.”

Some linguists believe that, with lack of better words, the terms “TV” and “film” will become relics that take on new meanings. We still refer to the moving pictures we record on our phones as “video,” for example, even though they are no longer shot on videotape.

“People are still referring to them in the same sort of monikers,” said David Zucker, head of TV at Ridley Scott’s production company Scott Free, which also makes movies like Alien: Covenant and Blade Runner 2049. ”But everyone seems to have different ideas about what they mean.”

Netflix calls itself “internet TV.” YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki says YouTube “is not TV. And we never will be.” The Internet Movie Database doesn’t even have a classification for web series, so all those on the platform are listed as “TV series.”

“I’m terribly dissatisfied with the language that’s now associated with these changes,” said Rouhana. “‘Digital’ and ‘TV’ are sort of misnomers now.”

New TV?

Dissatisfaction drives change. New words arise when “we’re using our language and bump into an idea that isn’t expressed well,” David Barnhart, a long-time dictionary editor who specializes in new words, told Quartz.

“Podcast,” for example, was coined in 2004 to describe audio shows that weren’t too different from radio broadcasts, but could be downloaded to devices through the internet. It’s “pod,” as in the Apple iPod, and “cast,” as in broadcast. Apple no longer really makes iPods but the term remains easy to grasp and widely used, two of the factors that linguist Alan Metcafe said make new words stick.

DreamWorks co-founder Jeffrey Katzenberg is peddling the term “new TV”for his latest venture—creating short 6-10-minute series that are meant to be watched during down time on mobile devices. It’s similar to the way “new media” was used to described digital publishers. As of now, however, Katzenberg appears to be one of the only ones using “new TV,” which doesn’t bode well for the word’s longevity.

The term “TV” may very well stick around for awhile yet.

Grant Barrett, linguist, lexicographer, and host of the public radio show A Way with Words, thinks “TV” could become a skeuomorph, an architectural term borrowed into linguistics that refers to words and phrases that are rooted in fossilized meanings. “Dialing a phone” is one such phrase. It harkens back to rotary phones equipped with dials, or disks, that were used to make calls. Today, we simply tap the numbers or press the buttons on our phones, but the phrase is still popular.

“There is this natural conservative force to retain what’s already working that makes terms like ‘tape’ persist,” he says. ”It’s an artifact.”

Sometimes, an old word re-emerges and takes on a new meaning. Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan, for example, likes “motion pictures.” “I still use that old-fashioned term, because it covers both movies and television nicely,” he said in a Reddit AMA. I asked Michael Green, the screenwriter for Blade Runner 2049 and Logan, for his thoughts and he gave another suggestion via Twitter:

That accords with what others think. “I don’t know anyone of my peers who says, ‘I’m looking for a new digital series,'” said Signore, one of the YouTubers. “The term is just ‘show.'”

Incidentally, using the word “shows” for entertainment programs stems from a term from the 1300s use of the word as “exhibiting to view.” And “series,” or a set of programs with the same characters or themes” was adapted in 1949 for radio and TV. These older terms are versatile enough to span content that is no longer bound by its platform. After all, no matter what the method of consumption, stories are just stories.