A logo of a mother cat carrying a kitten by the neck with its mouth is supposed to symbolize the level of customer care and service offered by Yamato, Japan’s largest home-delivery company. According to its founder in 1919, “service first, profit after” was the company’s guiding principle (link in Japanese).

Yamato’s black-and-yellow logo is ubiquitous across Japan, as customers use the company to deliver same-day grocery orders, luggage to the airport ahead of a flight, or equipment to a music festival. The company’s 60,000 workers delivered 1.87 billion packages in the fiscal year ended March; 3.9 billion packages (paywall) were delivered in Japan in total last year. In addition, re-deliveries due to customer absence are free of charge in Japan—some 20% of packages (paywall) in Japan in 2015 were re-deliveries, according to government estimates. (Leaving parcels unattended outside someone’s door is a no-no in Japan.)

But in today’s Japan, faced with a shrinking labor force and an insatiable demand for convenience and ever-faster deliveries, that level of service isn’t possible without something having to give. That’s particularly hard in a culture that prides itself on its level of service, and one where workers don’t usually speak up to managers about hardships, let alone ask for raises—and as a viral video last year of a delivery worker for Yamato’s rival Sagawa Express taking out his anger on a bunch of parcels shows, many employees are already at a breaking point.

Hiring more workers isn’t the immediately obvious solution, as Japan faces its tightest labor market in over four decades (paywall). In any case, delivery companies are hardly the employer of choice for Japanese people at the moment, given the government’s crackdown against companies that violate labor laws—Yamato recently reported a loss for the second-straight quarter because of charges for unpaid overtime.

Nor is raising the cost to consumers an easy task. Price increases aren’t only a potential affront to cultural practices, but a shock to the system (paywall) in a country long accustomed to deflation.

“There is a deep-rooted belief in Japan that when consumers purchase a product, they can expect any associated services to be free,” wrote Ogawa Kosuke, a professor at the Hosei Business School of Innovation Management in Tokyo, in May. “The delivery crisis is sparking a forward-looking discussion in Japan on whether the time has come to curtail excessive service.”

Yamato, and consumers, are changing their practices and expectations. After discussion with the union (paywall) in March, Yamato said it would do away with the noon to 2pm delivery window for its workers to allow them a proper lunch break and bring forward the re-delivery deadline by an hour to 7pm. In April, Yamato said it would stop making same-day deliveries for Amazon. Amazon, which is now using its own logistics network for deliveries, charges an extra fee for same-day grocery deliveries in parts of Tokyo.

“[It] is possible to change the way one works without discarding the customer-first principle, and it can also lead to more polished service,” wrote Yoshie Komuro, CEO of a consultancy called Work-Life Balance, citing an apparel retailer in Japan that recently tried to reform its work culture.

To ease the burden on delivery companies and reduce the waste in manpower and energy from missed deliveries, the government is also subsidizing the installation (paywall) of delivery lockers being installed around Japan, and delivery workers are increasingly partnering with (paywall) Japan’s ubiquitous convenience stores to facilitate pick-ups.

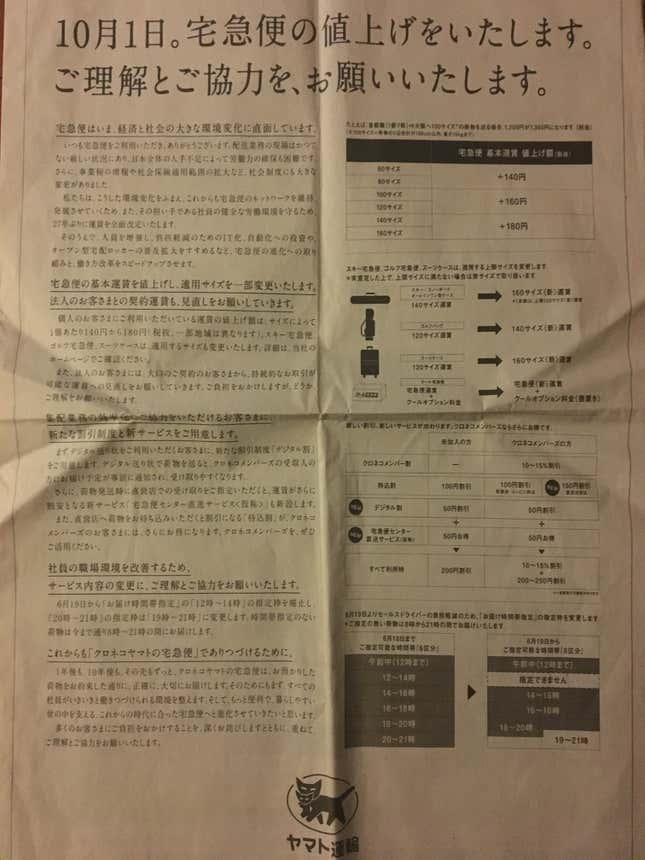

But Yamato finally bit the bullet and announced in April that it would raise its prices starting in October for basic shipping for the first time in 27 years, from ¥140 ($1.30) to ¥180. Sagawa Express will follow suit (paywall) in November. But Yamato didn’t do so without a demonstration of deep contrition—it took out a full-page ad in a Japanese newspaper explaining in detail the reasons behind the price increase, and asked customers for their understanding and cooperation.