In bathroom mirrors all over the world, countless little black girls have thrown a T-shirt over their heads to pretend they finally have the long flowing hair of their favorite pop star. What seems like an innocent moment is filled with shame and the internalization of the message that they are not good enough.

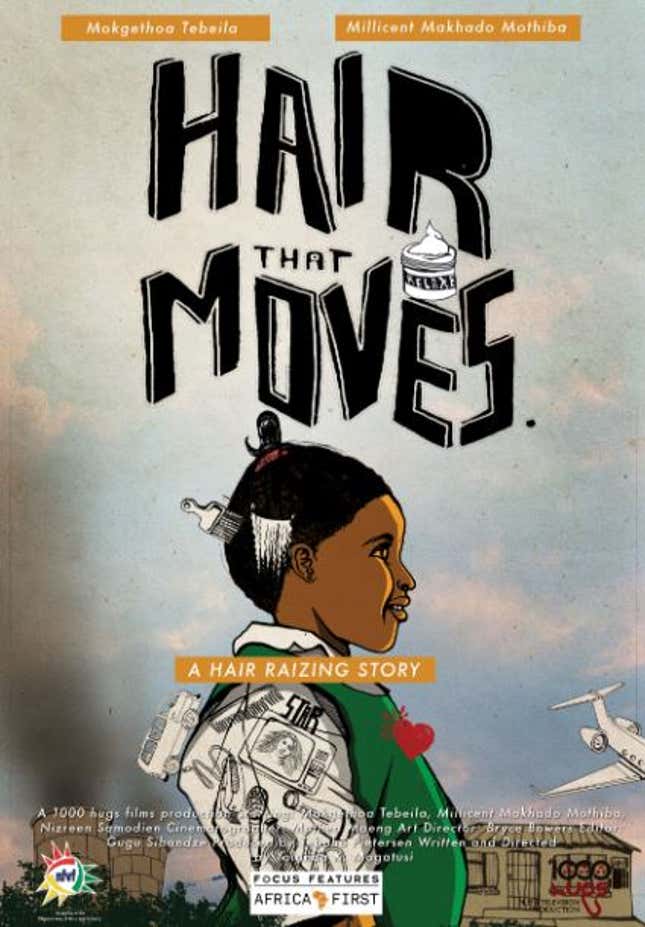

A poignant South African short film has captured that moment and the emotions that swirl around it. Hair That Moves follows the story of Buhle, an 11-year-old girl who is convinced that winning a talent show will change her life. Blessed with a voice beyond her years, Buhle is convinced that what she really needs is flowing hair like her pop idol.

Hair That Moves captures a story that instantly recognizable and yet often overlooked. Filmmaker and screenwriter Yolanda Mogatusi completed the short film in 2015 after winning the Focus Features Africa First short film program. At screenings in the US and South Africa, men and women in the audience have stayed behind to tell her how much of themselves they see in Buhle.

Now, in South Africa, the film finds itself contributing to crucial conversation in the country it was set in. In the last year, South Africa has seen real-world examples of schoolgirls facing rejection over their hair as they try to fit into the country’s elite schools.

“I just wanted to make a film about self-love and self-acceptance,” said Mogatusi.

In doing so, her short film explores topics class, segregation and race. Buhle’s long commute in a cramped taxi from home in Soweto to school Johannesburg’s northern suburbs affects her grades and shows the lingering effects of apartheid’s city planning, for example.

Buhle is a “third culture kid”, navigating between life in a black township and a manly white private school. She also struggles to translate her new ideas to her hard working, tense mother, who also dons a sleek hairpiece to cover her own hair.

Like so many black girls, at one point Buhle turns to hair relaxer. The ensuing disaster is hilarious and reminiscent of a scene in Zadie Smith’s debut novel on race and identity, White Teeth. This scene has reminded other viewers of an anecdote in South African writer Kopano Matlwa’s award winning novel Coconut, says Mogatusi.

“Everyone knows that burn but everyone keeps going back,” says Mogatusi.

This was a story that Mogatusi admits that she herself overlooked. Her first stab at the competition was with the stereotypical Africa story that she thought judges would want to see from the continent, until it was rejected.

Tapping into her own experience led to the kind of success that has brought her short film to Amazon’s streaming platform. If anything, it speaks to the importance of cultural representation on screen and the importance of telling everyone’s story.

“I know what it’s like to be a Buhle,” she says. Many in her audience will know too.