In his speech announcing a new Afghanistan strategy last night, US president Donald Trump said, “nearly 16 years after [the] September 11th attacks, after the extraordinary sacrifice of blood and treasure, the American people are weary of war without victory.” He went on to lay out a plan for an essentially open-ended war, having criticized this very same policy in a 2013 tweet using the same “blood and treasure” phrase:

Trump wasn’t the only one to use the phrase. Writers at Breitbart (“Americans can look forward to yet more blood and treasure being spent abroad”), the Sydney Morning Herald (“Afghanistan has limped along, consuming endless blood and treasure“) and many other publications used it to comment on Trump’s Afghanistan strategy.

In recent days, it’s also been used to decry white-supremacist rallies (“Have we forgotten…how this country paid dearly in blood and treasure to reunite this land?”) and to warn about a showdown with North Korea (“despite the possible shakiness of the intelligence and the immense logistical difficulties involved, to say nothing of the projected costs in blood and treasure“). Type the name of just about any war into Google, along with the phrase “blood and treasure,” and you will get results.

“Blood and treasure” obviously just means “lives and money.” But nobody ever writes about the “blood and treasure” that will be lost to a tsunami, an Ebola outbreak, or the opioid epidemic. It’s specifically a war cliché—a kind of rhetorical cape that writers and politicians throw over their shoulders to lend their opinions a little more gravitas.

So where did it come from and why is it so popular?

According to the blog Grammarphobia, it cropped up first in the 1640s and became popular around a century later, thanks largely to the influence of the essayist and satirist Jonathan Swift, who was fond of employing it in his political writings. Politicians started adopting it to decry wars they didn’t agree with, or to steel their populations for wars they thought inevitable. (John Adams, 1776: “I am well aware of the Toil and Blood and Treasure, that it will cost Us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States.” Abraham Lincoln, 1862: The idea of America “demands union, and abhors separation. In fact, it would, ere long, force reunion, however much of blood and treasure the separation might have cost.”)

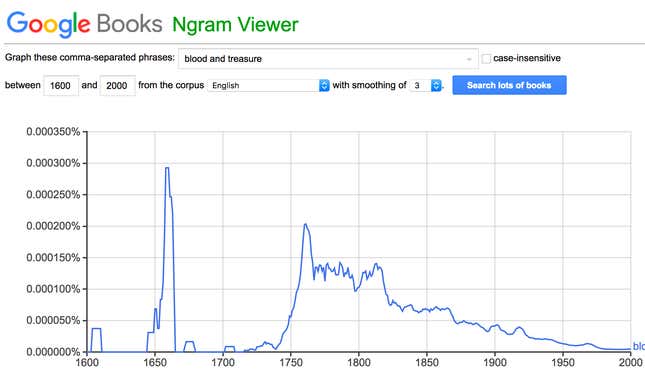

Google’s Ngram viewer, which tracks the frequency of phrases in books, shows “blood and treasure” declining steadily after the early 1800s. But that doesn’t track newspaper articles.

For a proxy of that I searched for the phrase in the New York Times since 1910. The biggest peak in its use was during World War I, and it’s notable that neither World War II nor the Vietnam war produced a similar spike. It has had a big resurgence with the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. That might be at least partly because the Times has simply published more total pieces each year as the internet has taken off. But the fact that the phrase has since declined again shows it is still something people reach for when talking of war.