As climatologist Katharine Hayhoe points out, seasonal hurricanes are a natural part of the weather system in the Gulf coast, and attributing the cause of a single storm entirely to climate change is currently an impossible task. “Once you get down to a small regional level, hurricanes are so rare and random that you would not be able to detect a robust trend even if there was one,” says John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas’ state climatologist.

But did climate change-driven factors make Hurricane Harvey more destructive?

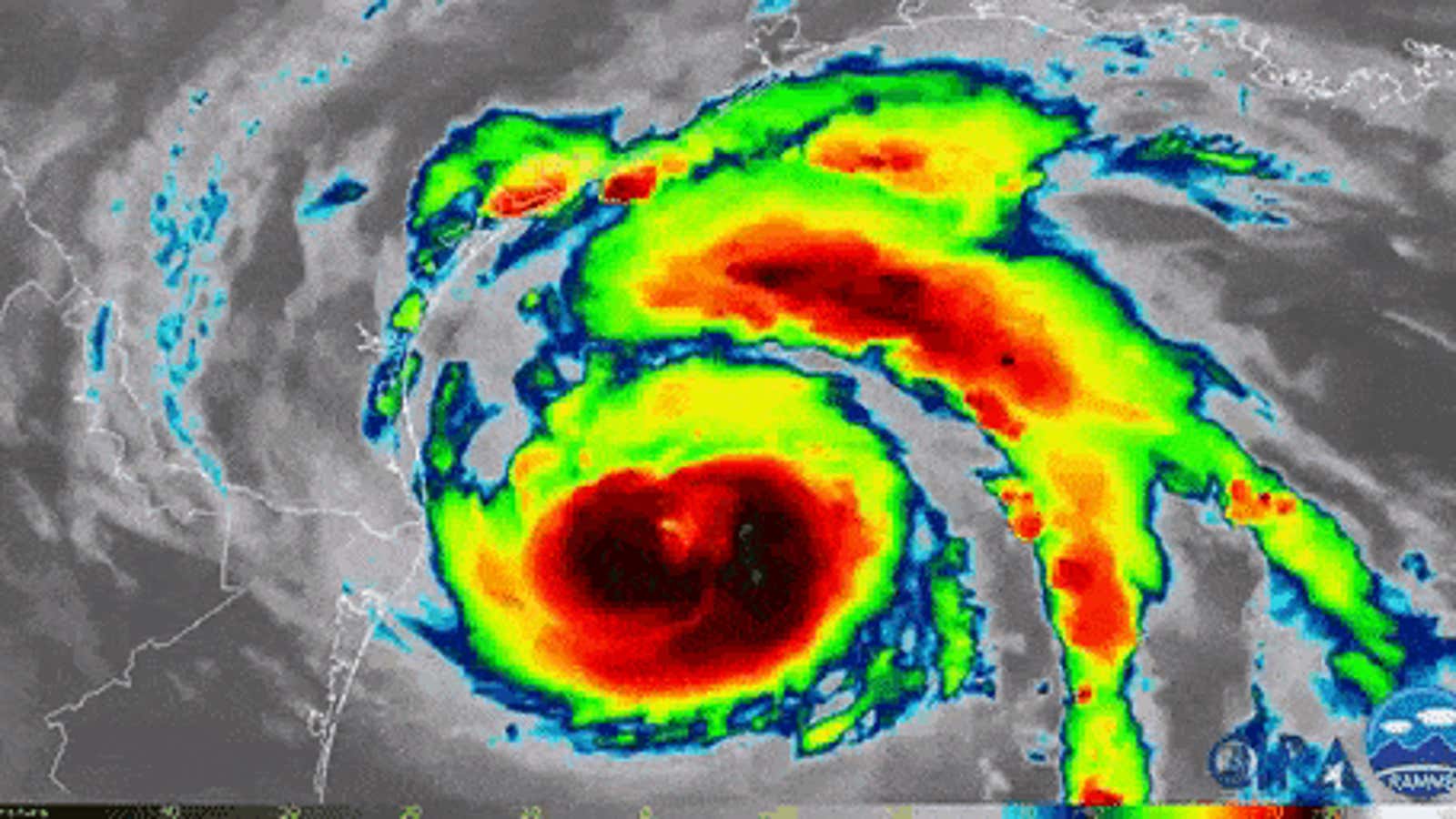

The waters of the Gulf of Mexico have been warmer than average this year, with bathtub-like temperatures breaking heat records all last winter.

Researchers can point to a direct relationship between warmer water temperatures and an increase in tropical cyclone formations, but the link between warm water and hurricanes is less clear, in part because hurricanes require several other ingredients, like specific wind patterns, to form.

Climate change is definitely setting up conditions that are known to make storms more destructive, including heating up the oceans. “The warmer the Gulf water is, the greater the amount of moisture will be available” to fuel rainfall, Nielsen-Gammon says.

Officials at the National Hurricane Center predict Hurricane Harvey will bring torrential rainfall of 15 to 25 inches to Texas—with “isolated maximum amounts of 35 inches over the middle and upper Texas coast,” the Center wrote in its latest warning.

Climate change is also heating South Texas faster than most other regions in the US, and the area has been setting heat records all summer. Warmer air temperatures mean the air has a far greater carrying capacity for moisture—which translates to even more rainfall, and more floods.

“We’ve seen an increase of 30% in very heavy rainfall and intensity across Texas,” Nielsen-Gammon says. The US Environmental Protection Agency’s website notes that rainstorms in Texas are “becoming more intense, and floods are becoming more severe…In the coming decades, storms are likely to become more severe.”

And then there’s sea level rise; global warming is raising sea levels along Texas’ coast by almost two inches per decade, according to the EPA. Sea level rise makes storm surges “that much higher,” Nielsen-Gammon says.

Officials currently warn the storm surge for Harvey is expected to bring “life-threatening” flooding at heights of six to 12 feet above ground level along the coast.

Workers at 39 offshore petroleum production platforms and an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico were evacuated on Thursday in anticipation of Hurricane Harvey, CNN reports. Over the past century, offshore platform heights have risen with sea level and storm intensity, the Atlantic reports; in the 1940s, they were 20 to 40 ft above sea level. In the 1990s, they rose to 70 ft. Now, after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, platforms in the Gulf sit 91 ft above the sea surface.

Later, after the storm is over, scientists who work on “event attribution” may try to assess whether Hurricane Harvey would have been less intense in the absence of human-driven climate change, much like researchers did with Hurricane Katrina; for example, one team found that under the climate conditions of 1900, Katrina’s storm surge would have been anywhere between 15% and 60% lower.

But for now, researchers, including experts at NASA, point out that the already-clear effects of a changing climate—warmer air, warmer water, and sea level rise—could make any storm that develops more intense.