As the US confronts the question of what to do with the statues of Confederate generals like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, Australia is contending with its own contentious memorials.

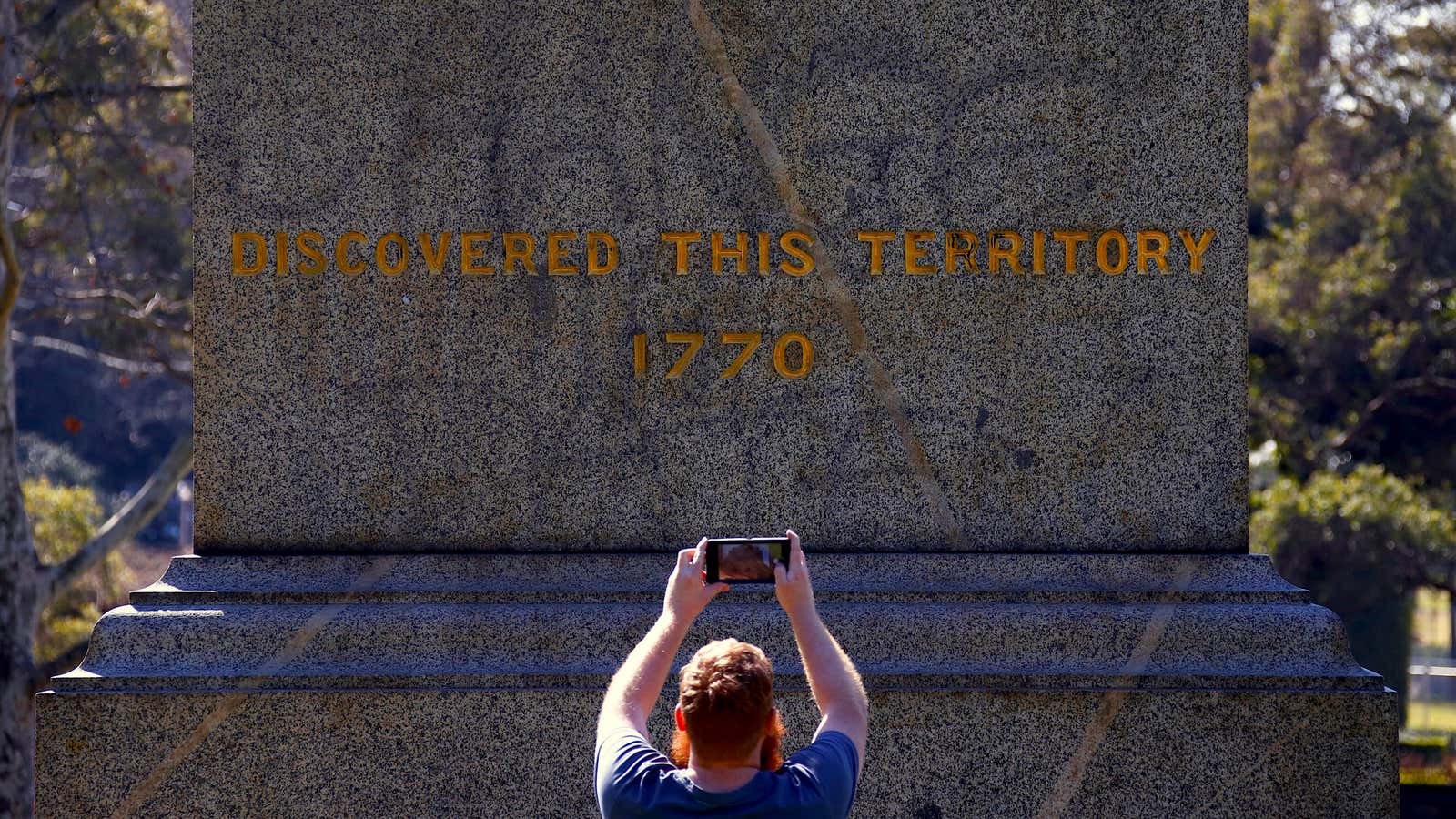

“Australia is awash in memorials glorifying settlers and colonists, some of whom did quite heinous acts,” wrote Freya Higgins-Desbiolles, a senior lecturer in tourism at the University of South Australia. These men include explorer James Cook who “discovered” Australia in 1770, and Lachlan Macquarie (pdf), a former governor of the state of New South Wales, whose statues were vandalized over the weekend in Sydney’s Hyde Park.

Cook and Macquarie’s names are memorialized across Australia in everything from public spaces to schools, but many contend that it’s a version of Australia history that excludes its aboriginal population. Aboriginals had of course been living in Australia for thousands of years before Cook’s arrival; and while Macquarie’s tenure as governor of New South Wales is generally seen as a relatively progressive one, he nevertheless presided over schools that forcibly took “unenlightened” aboriginal children (pdf) from their homes to be forcibly re-educated, and authorized troops to kill aboriginals in 1816.

The vandalization of the statues is the latest incident in an ongoing debate in Australia over its history, which many contend excludes aboriginal perspectives. One of the slogans spray-painted on the statues read “change the date,” a reference to a campaign supported by some Australians to shift the Australia Day celebrations from Jan. 26, as the date commemorates the day that 11 convict ships from Britain arrived on the island and raised the Union Jack in 1788, which subsequently led to white settlement and the decimation of aboriginal culture. Some want to rename statues and other places named after these men. Stan Grant, a journalist and vocal advocate of indigenous rights in Australia, wants to change the descriptions on statues that say Cook “discovered” Australia. Sydney’s Lord Mayor Clover Moore said she supported having a discussion about changing the inscription on the Cook statue.

Like the debate in the US, many in Australia think that removing or renaming these public memorials is akin to destroying the country’s history. Prime minister Malcolm Turnbull said he disagreed with Grant’s proposal to edit the statues, and called the such moves a “Stalinist exercise of trying to wipe out or obliterate or blank out parts of our history.” Turnbull has also said that he didn’t support changing the date of Australia Day, and stripped Yarra city council in Melbourne of its right to hold citizenship ceremonies after the council decided to stop celebrating Australia on Jan. 26.

Aboriginal leader Warren Mundine echoed the “Stalinist” criticism, and said “if you start mucking around with statues then you might as well start tearing down the pyramids.” He said the answer was to have more memorials to indigenous Australians. Opposition leader Bill Shorten said that putting an “additional plaque” at the Cook statue in Sydney was one way to better reflect Australian history and the way that ”First Australians haven’t shared the success that many other Australians have enjoyed.”

One example where this has been successful, according to Bruce Charles Scate, a historian at Australian National University, is in the city of Fremantle in Western Australia, where ”a monument that celebrated the racism that mars Australia’s past has today become a symbol of dialogue and reconciliation.” A monument built in 1913 to commemorate three white explorers that painted aboriginals as “savages” stood unchallenged until the 1980s (pdf, p8), when aboriginal elders unveiled their own plaque with their own version of what happened when an expedition led by settlers resulted in a massacre of indigenous Australians. The indigenous answer reads, ”No mention is made of the right of aboriginal people to defend their land or of the history of provocation which led to the explorers’ death… This plaque is in memory of the aboriginal people killed… It also commemorates all other aboriginal people who died during the invasion of their country.”

In this way, said Scates, “one view of the past takes issue with another and history is seen, not as some final statement, but a contingent and contested narrative.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Jan. 26 as the day that James Cook landed in Australia.