In 1959, the design world became briefly obsessed with a living room in a tiny town in Columbus, Indiana. A lavish 20-page feature in the February issue of House & Garden magazine showcased the impeccable home of Xenia and J. Irwin Miller, designed by the great architects Eero Saarinen and Alexander Girard.

At the heart of their modern home was a 2.5-ft-deep “conversation pit”—a sunken 15-foot-square section of their living room, lined on all sides with couches.

Saarinen had began experimenting with pits in the 1940’s as a way to create divisions in open-space floor plans. He later used a version of the conversation pit in the iconic TWA terminal at New York’s Laguardia airport. The polymathic Girard, who had ground-level “built-in banquette pits” in his own home, worked on the house’s interiors.

For the Millers, he chose colored textiles for the throw pillows as a counterpoint to the house’s stark white-on-white modernism. House & Garden described the pit as a “brilliantly cushioned well” that hid the “unsightly tangles of chair and sofa legs, the ubiquitous end tables.”

The Millers were great patrons of modern design, so they were game for the unusual architectural feature. But not everyone was sold on the idea. Building in a conversation pit is no easy feat: More than a sunken living room, it involves excavating a hole deep enough to submerge furniture—akin to digging out a shallow indoor pool.

In 1963, TIME published a strongly-worded call to arms against conversation pits, imagining all the dangers lurking in the craters that had begun appearing in a growing number of bourgeois living rooms:

At cocktail parties, late-staying guests tended to fall in. Those in the pit found themselves bombarded with bits of hors d’oeuvrcs from up above, looked out on a field of trouser cuffs, ankles and shoes. Ladies shied away from the edges, fearing up-skirt exposure. Bars or fencing of sorts had to be constructed to keep dogs and children from daily concussions.

The only solution, TIME suggested, was to remove all trace of these regrettable architectural features. “A few cubic-yards of concrete and a couple of floor boards will do the trick. No one will ever know what once lay beneath.”

Living with a pit

A 1962 book called Design for Modern Living, had chapter on the conversation pit, as designer Timothy deFiebre recalls. Predicting its wide appeal, German authors Gerd and Ursula Hatje wrote:

An idea for a new shape in sitting areas originated in the United States and will certainly be copied abroad for its mixture of romanticism and practicality…The conversation pit is a solution that combines an intimate and impromptu atmosphere with the possibility of seating a lot of people without much furniture in a relatively small area.

True enough, conversation pits popped up in modern homes around the world.

My grandparents’ house in Manila had one. My aunt and uncles remember how the indoor pit’s use evolved through their childhood. My aunt Dreena says that my grandmother, who we called Lola Aning, called the pit the “inside garden.”

“She planted different indoor plants to make it look like a Japanese garden,” Dreena recalls. “Mom hired a flamboyant decorator named Manny,” adds Francis, the youngest in the family. “They put large white stones and plants in there.”

Over time, my grandmother decided that maintaining an indoor garden was too much of hassle. She had granolithic flooring poured in to level the ground and transformed the pit into a music nook for guests and a hangout for her seven children.

Designed by the Filipino architect Marcos de Guzman in 1956, the six-bedroom house’s main flaw was the see-through roof above the conversation pit. No match for the regular onslaught of tropical typhoons in the Philippines, water constantly dripped from the ceiling.

The conversation pit saved the house from being completely flooded, functioning as a reservoir until someone could fetch a pail to catch the dripping or get a repairman to patch the roof.

A visit to the Millers

Since the Miller House was opened to the public in 2011, its meticulously preserved conversation pit has become a pilgrimage site for fans of mid-century modern architecture. Never mind the incredible gardens and landscape design by Dan Kiley. Everyone wants to see the living room.

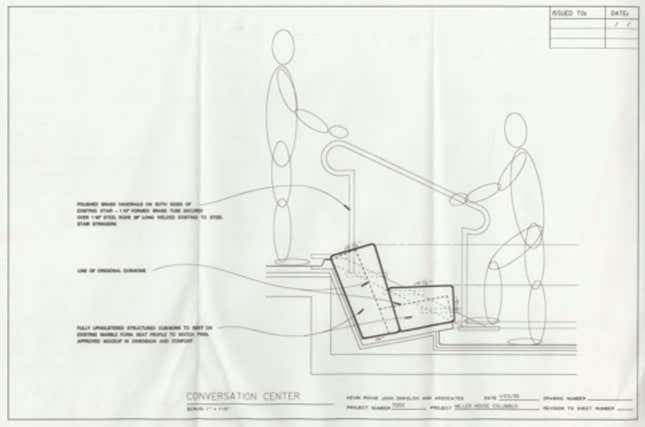

On a day trip to Columbus, Indiana last month, I joined a tour of the Miller House led by the site manager, Ben Wever, who pointed out some fascinating details: The angle of the steps down to the pit was calibrated so sitters couldn’t see up ladies’ skirts. The back cushions were thicker than usual to help sitters get in and out of the couch easier. The underside of the piano nearby was painted a bright red—a la Louboutin heels today—so sitters could have a nice field of vision when they looked up.

In the Millers’ senior years, a brass handrail was added to the floating steps.

Wever’s stories about the lengths Xenia Miller went through for the pit’s upkeep reminded me of my grandmother’s travails with maintaining her modest indoor pit.

Rise, demise, comeback?

By the late 1960s, conversation pits had become ubiquitous to the point where they lost their glamour. Saarinen himself called them “more or less” a cliché in a speech as early as 1960, according to architecture critic Alexandra Lange. In the decades since, they have generally been regarded as curiosities or nostalgic throwbacks.

But the feature is making a comeback, argues Kyle Chayka on Curbed, and with good reason:

Rather than sitting and watching Netflix, the enclosed pit meant that visitors watched each other. The people near and across from you were the entertainment, ringed around the fireplace or capacious table that often provided the pit’s center. Some of the more wholesome images, drawn from ads or interior decorating books, depict entire families lounging around a sunken couch, playing board games and strumming guitars.

Still, Maureen Dietze, a realtor with Alton & Westall Real Estate Agency, tells Quartz that selling a house with a conversation pit today would probably be a challenge.

“I think people would find it odd,” she says. “I think most would find it possibly a tripping hazard.” A house she’s trying to sell in Hancock, Massachusetts has a conversation pit with a safety wall and a hidden entertainment center. She has tweaked the pitch, calling it a “conversation-slash-media pit.”

Of course for lovers of mid-century design, a conversation pit is a selling point. Perhaps it has to do with the obsession with Mad Men-era style. Don Draper had one in his swanky Manhattan pad, which his ex-wife Betty examines with awe in this scene from the show:

Millennials, in particular, are avid about mid-century design, says the design historian Alessandra Wood, director of style at the interior design start-up Modsy. (The site’s online “style quiz” indicated the same.)

“Millennials love experiences, and the conversation pit is the ultimate mid-century modern experience,” explains Wood.

Or perhaps it’s has to do with that deeper yearning to be in a circle with other humans, instead of burying ourselves in the feeds from our devices.

“Historically, the conversation pit was about connecting with people, having personal conversations, and creating a more intimate environment to get to know someone or spend time together,” says Wood. ”While older generations might see the pit as a marker of dated design, younger generations are likely drawn to its novelty and ability to create a safe and intimate space in a world that’s increasingly full of impersonal experiences,”

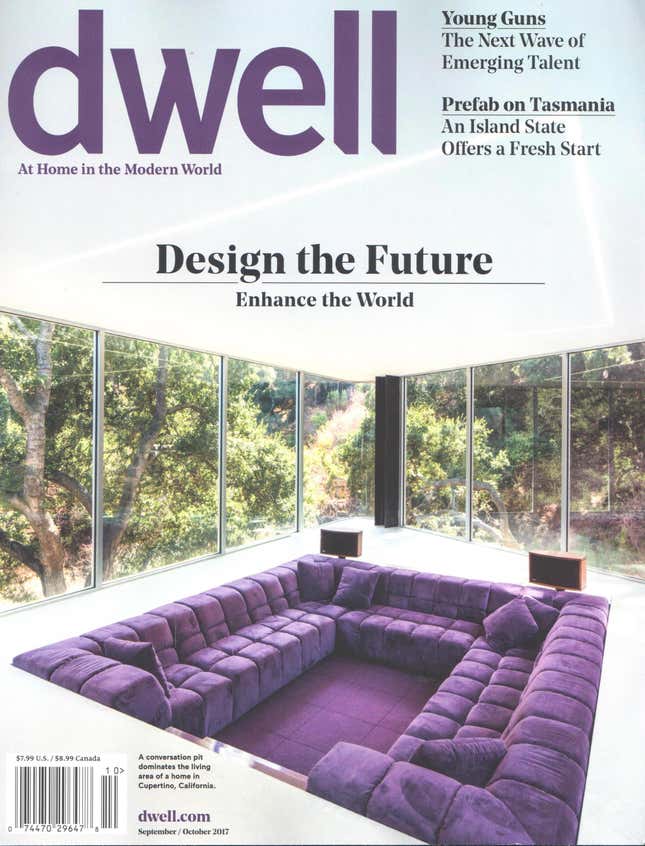

The cover of the latest issue of Dwell magazine features a conversation pit in a glass-enclosed room in the heart of Silicon Valley, complete with a grape-colored Tufty-Too sectional. Captioned with the words “Design the Future: Enhance the World,” the cover might be read as a call for balance amid our overly-wired tech environments.

When so many of us are addicted to our mobile devices and subsist on virtual messaging, perhaps it isn’t so ridiculous to dig a crater in the middle of the living room—if that’s what it takes to remind us to sit down with one another and to converse.