Chinese money dominates bitcoin, now its companies are gunning for blockchain tech

Beijing, China

Beijing, China

It’s a sweltering summer night when I’m invited to join a bitcoin miner from Shenzhen at a “bitcoin club” somewhere in downtown Beijing. I’ve just returned from visiting one of the world’s largest bitcoin mines and find myself at a gathering of cryptocurrency enthusiasts at a craft beer brewery in the Sanlitun nightlife district.

I excuse myself from the bitcoin meetup and resort to jumping in a pirate taxi because I don’t have a mobile wallet from Alibaba or Tencent—the primary way to hail and pay for taxis in the city. After paying in cash—now a rarity in China’s mobile payment saturated cities—I disembark, then get lost amid Beijing’s ancient hutongs, the narrow alleyways that link China’s traditional courtyard residences.

My host puts me out of my misery by sharing his location on a real-time map over our WeChat direct messages. Now drenched in sweat, I meet Jack Liao, who runs a bitcoin mining firm called Lightning Asic. He leads me through a dark hutong, coming to a set of carved wooden double-doors. Pushing them open, we enter into the courtyard of a palatially renovated villa. This is my first look at the elusive “bitcoin club.”

The club is located in a 2,000-square-foot villa with a staff of 15, including cooks, cleaners, and wait people. It has two guest rooms, a dining room that hosts two dozen people, a professional Texas Hold ‘Em table emblazoned with the legend, “Faith in Bitcoin,” an automated mahjong table; shelves stacked with fine wine and liquor, a room for practicing Chinese caligraphy, and so on. The table stakes are bitcoin, AliPay credits, and sometimes even yuan, the only non-virtual currency accepted. Guests can sleep, eat, drink, and gamble for free if they’re acquainted with the miners who run the place. “People come here just to chat about projects,” Liao says.

The eye-popping villa bankrolled by bitcoin mining is a symbol of just how lucrative the cryptocurrency industry has been for some on the Chinese mainland. China is home to the world’s largest bitcoin mines, thanks to abundant and cheap electricity, and at one time the country accounted for 95% of the volume traded in global markets. Its central bank is experimenting with a blockchain-backed digital currency, and its biggest companies, from tech giants to industrial conglomerates, are racing to bake blockchain tech into major new projects.

All this points to a central question: How did stateless cryptocurrencies get so big in China, a country where the national currency—along with so much else—remains tightly controlled by the government? Why has bitcoin, along with other cryptocurrencies, flourished with so much vigor here in China? A two-week journey through bitcoin trading operations in Shanghai, mining operations in Inner Mongolia, and the club in Beijing hasn’t answered the question definitely—but it’s gotten me much closer.

Bitcoin is a political statement

Bitcoin began as an experiment in economics and politics, as a project to create electronic money that anyone could use but no one controlled, especially a sovereign authority. The code behind the new currency gave life to libertarian ideals like: money free from government controls on spending and taxation; transactions that could ignore a global, sometimes corrupt banking system; and freedom from central bank targeting of interest rates and inflation. It was also rebuke to the very notion of conventional money.

Bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, encoded a headline from the Times of London in the first block of transactions ever created on the bitcoin blockchain. It read: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

Given bitcoin’s political bona fides, it’s a great irony that Chinese companies and individual users are so dominant in its daily activities. The world’s biggest bitcoin miner is a Beijing-based company called Bitmain, which operates two mining pools that control nearly 30% of all the processing power devoted to bitcoin mining. It might seem that Chinese bitcoiners are carrying out some kind of libertarian protest against China’s ruling communist party, subverting the status quo by processing cryptocurrency transactions towards a yet-to-be-revealed political end.

They aren’t.

“In China, bitcoin is one thing and in America and Europe it is another thing,” Liao said as we sipped tea from porcelain cups on the villa’s top floor. Our host, Wu Bi, explains there is no competition between cryptocurrencies and the government-controlled renminbi, at least as the government sees it. “In China our government says bitcoin is not a currency, it is a commodity, so there is no chance it will compete with the renminbi,” Wu told me in Chinese, with Liao translating. “Bitcoin is a great idea, but in China we care more about blockchain.”

Wu and his Chinese compatriots are focused not on the currency, but on the technology behind it. Blockchain is simply a technical way to record encrypted transactions that are distributed across a computer network; once entered they cannot be altered. Instead of using blockchain, or bitcoin, as a permissionless cryptocurrency, banks want to shoe-horn some of bitcoin’s features into current transaction systems to create a low-cost network that, crucially, would require administrators to grant users access. Those administrators, of course, would be banks, or central banks. ”Different countries may have different ideas about what is government, and what is the liberty of individuals,” Wu says.

Bitcoin users I met in Beijing were similarly dismissive of bitcoin’s libertarian politics. They did not want to be named or quoted directly, but their argument was essentially this: People in China simply aren’t interested in bitcoin’s potential for political change. And besides, China’s closely controlled economy has delivered prosperity for now—what benefits does bitcoin bring besides as an investment that might appreciate?

Object of speculation

Ordinary Chinese bitcoin users I spoke to, and those who are served by the exchanges and wallet providers, are far more interested in the ability to speculate on bitcoin’s wild price swings—it’s just another way to make money as China continues to adopt characteristics of a market economy.

As it happens, bitcoin arrived just as a class of retail investors in China is growing in size, and seeking better returns than those offered by a restricted financial products market. Even the market for property in China’s top-tier coastal cities, usually reliable for spectacular returns, has been subjected to ever tightening lending restrictions by a government eager to curb speculation. ”[Chinese consumers] have had such limited channels for so long, and [bitcoin] was finally one that was not tightly controlled by the government,” says Martin Chorzempa, a research fellow specializing in Chinese internet finance at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington DC.

One seasoned observer of the Chinese bitcoin scene concurs. Eric Zhao is an engineer at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai and runs the widely followed Twitter account CN Ledger. Bitcoin became popular almost by default, because of the paucity of products for the Chinese retail investor, he says. “There are not many good investment choices for common people in China. Many people worry about inflation and lots of people feel insecure about their financial status,” he says. “They buy it simply because they believe it will appreciate in value.”

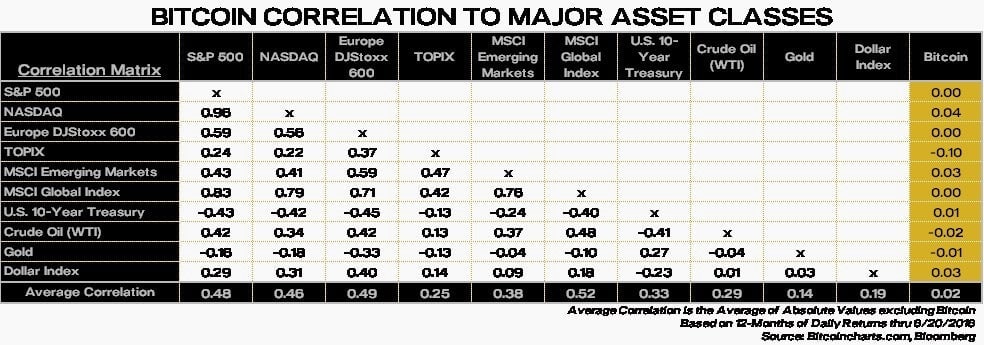

Uncorrelated to major asset classes and generally disconnected from the Chinese economy, bitcoin has been hugely attractive to Chinese investors already overweight domestic stocks and property. Indeed, research from Pantera Capital, a venture fund for blockchain companies, shows that bitcoin is almost completely uncorrelated to major equity, debt, and commodity asset classes. “Because [bitcoin] is globally connected, it’s not easily affected by the Chinese economy,” says Isaac Mao, a longtime entrepreneur and investor in China’s technology scene. “It may be the only economic activity fully connected to the global economy.”

Crackdown

The wild ride on bitcoin in China, however, braked to a stop Sept. 4, when China’s central bank began to take steps to halt domestic bitcoin trading. It started with a ban on “initial coin offerings,” followed by a shutdown of local bitcoin exchanges. China’s authorities have clamped down on bitcoin trading before, most notably in 2014, when the cryptocurrency was on a historic rally driven, in part, by Chinese money.

Now rumors are swirling that a ban on bitcoin mining may be enacted. But if the government has found bitcoin to be a potentially dangerous element in the country’s socio-political mix, why didn’t it crack down before? Instead, it has been relatively tolerant of a technology that was designed to weaken the state’s grip on money.

The rare true believer in bitcoin’s libertarian properties is Bobby Lee, an American who runs the world’s oldest bitcoin exchange, BTCC, in Shanghai. His firm was forced to shut down domestic trading through its BTCChina arm, although it still runs an exchange for non-Chinese traders. When we spoke before the crackdown in August, Lee was enthusiastic about government regulation, saying it would help the market mature. But he also struck a defiant note, saying that bitcoin’s design made it impossible for China’s regulators to shut down. “There is nothing [the Chinese government] can do. That is the beauty of [bitcoin],” he said.

I pointed out that the government could seize exchanges, and even bitcoin mining facilities, and compel their owners to run certain types of code or mess with transactions, thus damaging the cryptocurrency. Lee was sanguine. “They’ll want to control it, but bitcoin was not meant to be controlled,” he said. “You can make all the rules you want, and the question is, can they be enforced? With guns you can say, let’s make guns illegal. But with bitcoin, there’s nothing physical. It’s information, and there’s plausible deniability.”

The reality may be more prosaic. Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies are simply too small to bother the Chinese government much, says Isaac Mao, the investor and entrepreneur and one of China’s earliest bloggers. ”The [Chinese Communist Party] doesn’t recognize it as a threat, so bitcoin actually grows very quickly in China,” he told me at a cafe in Hong Kong, where he is now based. “But it’s too small. There is no scale. The market capitalization of bitcoin is about the same as PayPal,” or about $70 billion.

I spoke to Mao in August, but the crackdown doesn’t signal any political threat, writes Chorzempa of the Peterson Institute. It’s more likely that bitcoin trading is just collateral damage from a wider set of restrictions on alternative financial products that have caused billions in consumer losses. Regulators have reigned in not just crypto trading but peer-to-peer loans, trusts, and lending to non-bank institutions this year, Chorzempa writes: “The clampdown thus fits into a broader set of efforts to lessen financial market risks perceived by Chinese policymakers.”

Everyone hates inflation

To the extent that bitcoin trading and mining is a political statement, it’s a demonstration against inflation. Prices in China grew rapidly in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2008, hitting their highest level in decades in 2007. Inflation has moderated since then, but ordinary Chinese say they still feel the pinch.

Bitmain’s Micree Zhang, who developed its proprietary mining chips, says worry about inflation chewing up his earnings was one reason why he first became interested in bitcoin. ”Before I knew about bitcoin I disliked, and was very worried about, inflation. Especially in China in the last 10 years,” he said when I visited with him at Bitmain’s main facility in Inner Mongolia. “When I discovered bitcoin, I knew it was a good idea, very quickly.”

One bitcoin user I met in Beijing told me he was attracted to the cryptocurrency because the government couldn’t devalue it by printing more money, unlike the yuan. The Chinese government controls its currency far more tightly than other major economies.

This level of control can lead to panics. In 2015, the Chinese government devalued the yuan in an attempt to boost economic growth, sending shockwaves through global markets. While today the central bank’s move is seen as astute, at the time Chinese consumers were hit hard, worrying about paying more for everything from Australian beef to New Zealand milk.

Digging for digital gold

China has been the world’s largest electricity producer since it surpassed the United States in 2011. Cheap electricity is the crucial ingredient for a profitable bitcoin mining operation—and China has it in spades. So it’s no surprise that China has become a world center for the activity.

Take Beijing-based Bitmain, for instance. It’s the world’s biggest bitcoin miner, but the company doesn’t divulge its financial data, and there’s no easy way to find out because its beneficial owner is a trust in the Cayman Islands. But one longtime commentator in the bitcoin space, Jimmy Song, has performed an analysis of the firm’s likely profitability. His estimate: $77 million in mining profits for the firm this year, of which electricity and other operational costs come up to about $23 million.

It’s estimated that two-thirds of the world’s processing power devoted to mining bitcoin resides in China. These bitcoin mines take the form of giant warehouses filled with thousands of custom-designed machines and chips, all whirring away to check bitcoin transactions and compete for a slice of the 12.5 bitcoins awarded to a miner every 10 minutes. Collectively, bitcoin miners have collected more than $2 billion in revenue over the cryptocurrency’s nine-year lifespan.

Bitmain leads the pack as both a creator of bitcoin mining rigs and chips, and an operator of vast server farms. It’s now raised $50 million from marquee Silicon Valley investors including Sequoia Capital to expand to the US—perhaps reducing its exposure to Chinese regulations—and to develop a new set of chips for artificial intelligence.

Sheer scale

Bitmain’s position as the world’s largest miner is only the tip of Chinese industrial interest on blockchain technology. Last May, a Chinese company called Wanxiang Group, one of the world largest automotive parts makers, sponsored a blockchain hackathon at the Deloitte offices in Rockefeller Center in New York. Wanxiang plans to embed blockchain technology into a new “smart city“—a nine square kilometer plot of land with a planned population of 90,000 people and $30 billion in investment—that it is building from scratch near Hangzhou in eastern China. It was looking for the world’s brightest blockchain developers.

Wanxiang was offering $15,000 to teams who came up with an enticing blockchain project for the smart city, with an additional $1 million in funding. As Wanxiang executive Peter Liang clicked through his slides detailing how blockchains would power everything from the city’s electricity grid to its traffic control system and be embedded in Wanxiang’s factories, the handful of programmers in the room grew both skeptical and awed. “It’s so huge, it’s hard to even believe,” one developer told him.

Wanxiang isn’t the only Chinese conglomerate with blockchain dreams. Beyond cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, some of China’s biggest firms are betting on the technical ideas behind it to revolutionize their businesses. They’re placing much bigger bets than their counterparts elsewhere in the world, who are mired in small-scale trials, proofs of concepts, or slow moving consortia. Chinese companies “are not only moving faster, but the scale of their blockchain ambitions dwarf what we’re seeing elsewhere,” says Garrick Hileman, of the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

The Chinese e-commerce giant JD has already launched a food supply tracking system using a blockchain in Beijing supermarkets and online stores. The tech giant Tencent has partnered with Intel to develop a blockchain architecture. And the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, has said it’s researching blockchain technology as a way to potentially digitize the yuan.

Blockchains for industry

Unlike firms elsewhere in the world, Chinese companies sense an opportunity to unify the fragmented data flows flowing through their stupendously large and complicated factory floors and supply chains by marrying a blockchain data layer with Internet of Things devices. Conveniently, these applications are also free of the regulation and scrutiny that can slow down financial applications. “I personally believe that non-financial [applications] will go commercial sooner,” says Vincent Wang, Wanxiang’s chief innovation officer.

Taiwan’s Foxconn, one of the world’s largest contract manufacturers of electronics and best known for manufacturing Apple’s iPhone, sees blockchain as way for its suppliers to get easy financing. ”In China, 85% of SMEs can’t get financing,” Foxconn executive Jack Lee told a conference in New York in May. “They have to go to shadow banking … so it’s very inefficient and costly.” If Foxconn can leverage its current data on small businesses through blockchain, it could create a highly efficient supply chain that could also track delivered goods.

Just as mobile phones allowed China and emerging economies to leapfrog the rich world’s telephone landlines, blockchain technologies could help its industries skip the development of antiquated financial services models. After all, Chinese tech firms Alibaba and Tencent are already processing trillions of dollars through their mobile payments businesses. ”We are more interested in getting to a next-generation financial services business,” Foxconn’s Lee says. “That’s the key. As a side benefit for Foxconn, it will streamline the supply chain.”

Those kinds of observations make less worrisome the recent drop in China’s share of bitcoin trading volume as well as rumors on Telegram chat groups about an imminent crackdown on even China’s powerful bitcoin miners. Because Chinese money’s waning influence over the bitcoin markets may be replaced by control over an even greater prize.

As it continues to move from a rural to an industrial economy, China needs to leapfrog the incumbents and assert itself as a technology leader. Bitcoin and the ideas behind its blockchain may be one way to do that—and it may be why China has been a leader of a stateless cryptocurrency for so long.