When Lenora Chu, a Chinese-American, enrolled her son in an elite public school in Shanghai, she was in for a few surprises. Her son was force-fed eggs, a food he hated. When Chu questioned the teacher about her methods, she was roundly reprimanded for questioning a teacher’s authority. Her child was taught that there was a “right” way to draw rain. And the school refused to administer his asthma medicine because his condition did not warrant such individual attention. In Chinese schools, it is the group, not the child, which is paramount.

And yet, Chu did not respond with condemnation, but instead praise.

She went on to write a book about the experience, Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to Achieve, dissecting the secret to China’s superior academic results. She argues that China’s success derives mainly from two things. First, teachers have authority, parents respect it, and this enables superior learning. Also, kids learn early that it is hard work and not innate ability that will shape their success.

“The Chinese parent knows that her kid deserves whatever the teacher metes out, no questions asked. In other words, let the teacher do his or her job,” she wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

Not so long ago, Amy Chua wrote the Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother arguing that Chinese parents don’t coddle their kids (paywall), thus producing stronger, more resilient (and high-achieving) human beings (you may, for instance, recall she did not let her daughter go to sleepovers for fear it would interfere with her work). Chu argues teachers don’t coddle either, and as a result, kids develop skills and resilience American children couldn’t even begin to imagine. High expectations are set and kids learn to meet them. Ability is what breeds confidence, not praise over mere participation.

By contrast, American parents, as Chu describes them, tend to think cultivating children’s confidence is paramount, even when it leads to A grades for mediocre math work. Chu seeks to understand which system better prepares kids for the future, and the right roles for parents and teachers. Academic achievement or social and emotional well-being? The right to challenge authority or the respect to defer to it?

Teachers deserve more authority than parents

To Chu, and many others, there’s a certain brand of over-achieving, privileged American parents, who in their quest to make sure their kids succeed, neuter teachers, thus rendering them less able to teach our kids. Parents undermine these teachers by believing they know best (and let’s be honest—the only thing they know about teaching most of the time is what they have experienced personally, in classrooms that existed before the internet). She writes:

Educational progress in the US is hobbled by parental entitlement and by attitudes that detract from learning: We demand privileges for our children that have little to do with education and ask for report-card mercy when they can’t make the grade. As a society, we’re expecting more from our teachers while shouldering less responsibility at home.

Americans in the American system have made a similar case. Jessica Lahey, a middle school teacher and author of The Gift of Failure, argues that kids are being rendered helpless by (loving) parents who want to protect their children. If we resolve their fights on the playground, or extract the grades we want from their teachers, we are precluding them from learning these skills and thus failing to help them build autonomy (and thus we end up with things like “Adulting School”).

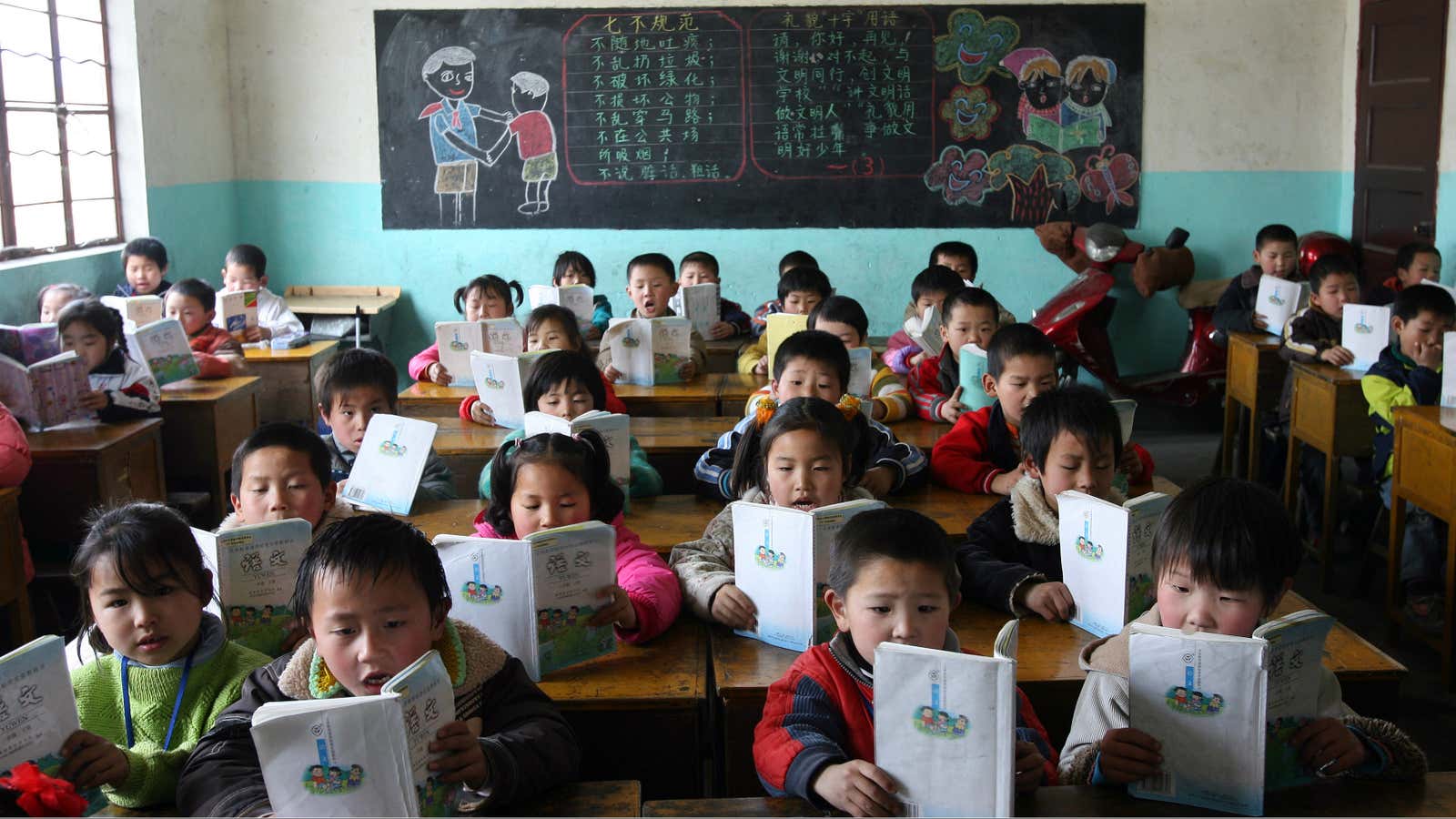

Andreas Schleicher, head of the education directorate at the OECD, argues that good teachers are a critical piece of the academic success of Shanghai schools. He says teachers he has observed in China do not view their role as teaching a child a subject, but instead shaping a child’s values and character. Kids play a role in cleaning classrooms; teachers collaborate with parents. Teachers demand high performance, but they also help kids achieve it, he says. In PISA, a test administered to 15-year olds around the world, Shanghai has won many top rankings, compared to a middling performance from the US. Of course, Shanghai is a megacity and the US a gigantic, diverse country, making the comparison tricky. Massachusetts, for example, would have ranked 9th in math and 4th in reading in 2012, far better than the whole US.

Mina Choi, a journalist who educated her kids in Shanghai primary schools, has written extensively about the pros and cons of Shanghai’s system. Her six-year-old had three hours of homework, and no friends (everyone was too busy doing homework). Much of the learning was rote, including when it came to writing essays (her son was encouraged to copy other essays to learn the art). She sometimes wondered how many kids understood the math versus knowing the answer from memorizing it.

But at least for primary school, she said she would do it all again. ”It’s rigorous, it’s demanding and it stresses hard work,”she said.

She hasn’t read Chu’s book, but agrees that lack of respect for teachers in the US is a problem. An experienced teacher knows more about what a 7-year-old needs to know, how he learns, and how to teach him than a parent, she said. “In America, a parent’s opinion is as valid as the teacher’s. It shouldn’t be.” That lack of respect carries over to US teachers’ pay, and the fact that state and local governments invest woefully little in their professional development. American parents’ complaints often stem from a lack of faith in the system.

Kids can handle tough love in the classroom, just like in sports

Both Chu and Schleicher, from the OECD, suggest there is another critical difference between the US and China. Teachers in China believe every child can succeed, regardless of income or background. They believe—and teach—that achievement requires hard work, and is not predicated on innate ability.

PISA scores only tell us so much about the quality of education, but they show that the 10% most disadvantaged 15-year-olds in Shanghai have better maths skills than the 10% most privileged students in the US and several European countries.

Chu points out the irony that Americans are not afraid to demand hard work and achievement from their kids in sports. If a child comes in last, it’s because he needs to work harder, not because he’s incapable of kicking a ball. “A ninth-place finish in the 100-meter dash suggests to us that a plodding Johnny needs to train harder. It doesn’t mean that he’s inferior, nor do we worry much about his self-esteem.”

Research from Carol Dweck, a Stanford psychologist, shows that kids who believe it is effort and not ability that matters, do better. Chu writes: “Chinese kids are used to struggling through difficult content, and they believe that success is within reach of anyone willing to work for it.” As a result, the government can set high expectations and kids can be taught to meet them. In the US, she notes, “parents have often revolted as policy makers try to push through similar measures,” such as the Common Core. Chu cites research showing that ethnic Asian kids outperform whites because of effort, not ability, and their belief that the effort matters.

Should we prioritize the individual child, or the collective?

A child’s life can feel a bit zero sum. Three hours of homework is three hours that child is not playing with others, exploring a playground or playroom, and setting his imagination free. Childhood is short, and many think it should be protected from high-stakes testing, rankings, and stress.

The question, then, is whether all the rigor of the Chinese system is worth the cost.

Yong Zhao, a professor at the University of Kansas’s school of education, shows that the better countries do on PISA, the worse they tend to score on being entrepreneurial (he uses the Global Entrepreneurship Model (GEM), the world’s largest study of entrepreneurship). Research consultancy ATKearney took that work further, showing that top PISA-scoring countries had an average perceived entrepreneurial capability which was less than half of that of mid- and low-scoring countries. So the kids may do well at math and science, but they’re not budding Mark Zuckerbergs.

Choi, the journalist, argues that the East Asian approach has other fatal flaws. Many kids are only children, and the devotion to them is absolute. Parents are willing to do anything for their children’s education, and children, in response to the pressure, often feel the need to cheat. Having left Shanghai four years ago, Choi says the system there is “not sustainable because of the corruption, the grade-peddling, the mystery about why grades were given.”

What’s more, giving teachers total authority doesn’t necessarily lead to better learning. Chu cites one 2004 study defending direct instruction, where teachers show children how to solve problems, a method more prevalent in China. While direct instruction is key to learning some things, context matters, there are plenty of other studies that show that when kids figure things out on their own, it activates deeper learning, and potentially sparks more of a desire to learn.

The reality is there are some benefits to both individuality and community, academic results and personal development. Zhoa says the US and UK are trying to emulate Asia’s testing prowess, while China is trying to make its system more Western, less monotonous, and more focused on problem solving and creativity. ”East Asians have witnessed first-hand the horrendous damage of their education on children: high anxiety, excessive stress, poor eyesight, lack of confidence, low self-esteem, and lacking life skills,” he writes. In the less extreme approach of Finland, for example, kids who have little homework or high-stakes testing report higher satisfaction levels and great PISA results.

When offered only extreme options, either path can feel like a gamble. “I would rather err on the side of over-education, not under-education,” Choi said (and wrote in this essay), referring to China’s more rigorous curriculum.

Chu says her kids got the best of both. “My son is imaginative when he draws, and has a great sense of humor and a mean forehand in tennis. None of these qualities has slipped away, and I now share the Chinese belief that even very young kids are capable of developing a range of demanding talents.”