Can you imagine what you would want to see if you were stuck for years in a cell with no windows, a place small enough for you to be able to touch both drab, bare walls if you stretched out your hands? Where you had very limited access to books, magazines, any stimulation from the outside world?

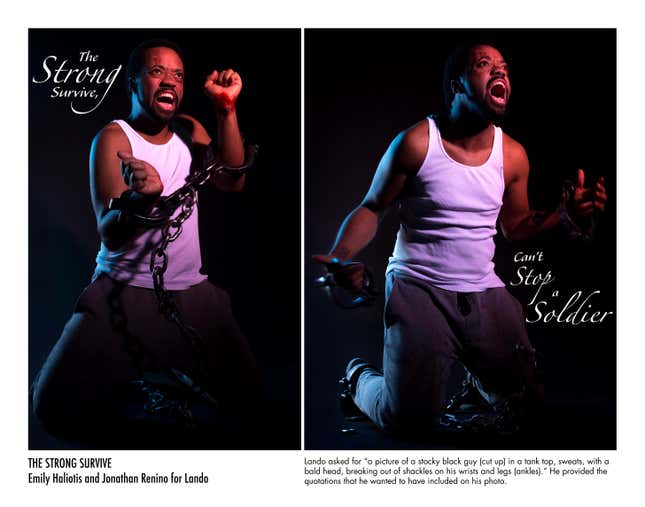

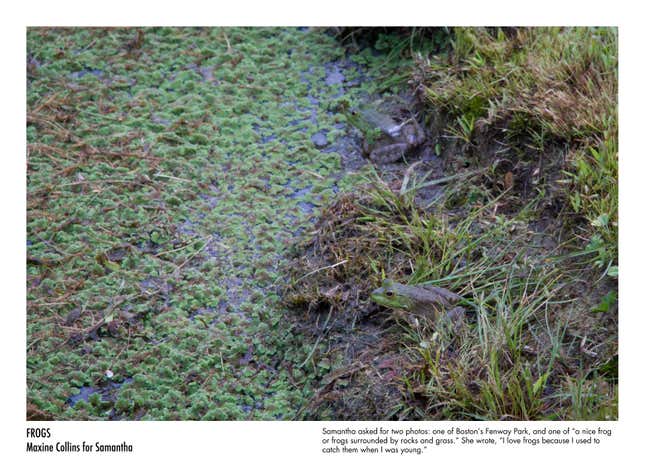

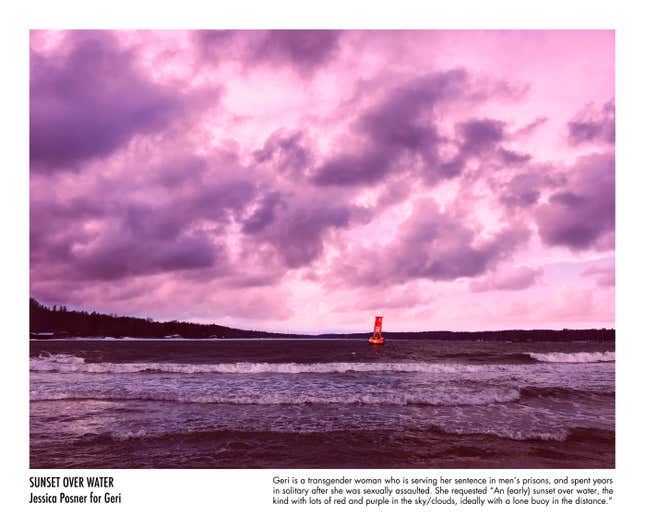

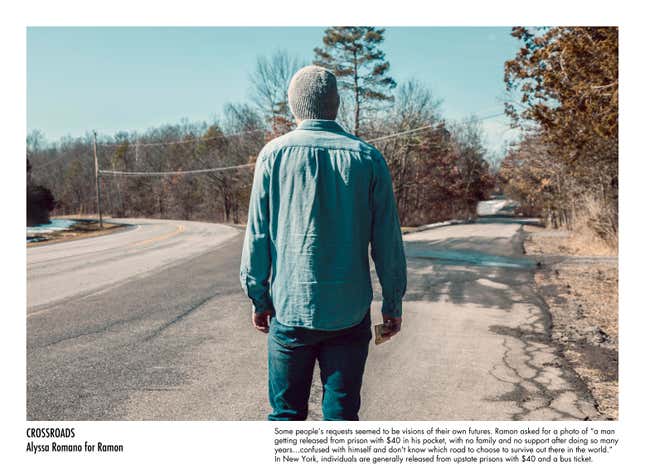

The project “Photo Requests from Solitary” explores this very question, offering inmates held in solitary confinement a chance to ask for any image that they want, and to get their request fulfilled by professional photographers, artists. The inmates’ ideas range from the mundane to the elaborate—from a simple photo of a frog in its natural habitat, to an imaginary scene where a black man dramatically unshackles.

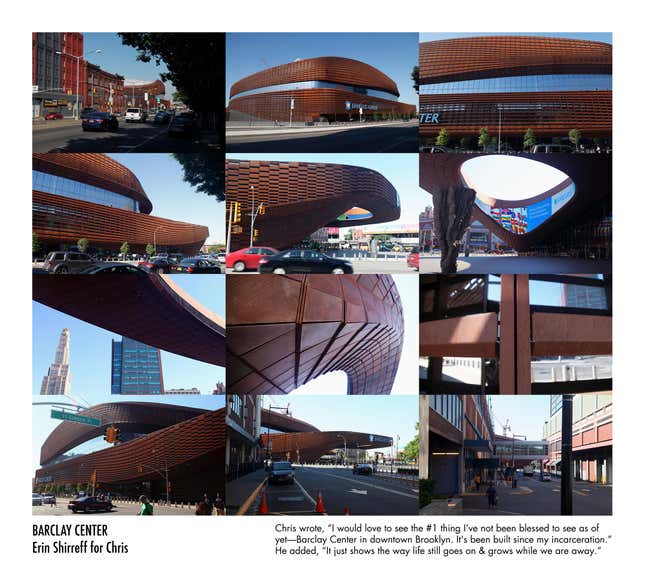

The exhibition opened Sept. 13 as part of Photoville, a photography festival in New York’s Brooklyn Bridge Park. Viewers see the requests and the photos alike. It’s meant to raise awareness about solitary confinement, as a movement to abolish isolation in New York prisons is gaining ground. Meanwhile, the photos, sent to inmates in their cells, provide them some form of relief in conditions of extreme sensory deprivation and isolation proven to be psychologically damaging.

“The idea is that human imagination can survive even this,” Jean Casella co-director of the watchdog group Solitary Watch, and one of the organizers of the exhibit, tells Quartz. “When you ask people what they want to see, there’s never any shortage of images or fantasies…Part of the message of this show is that you can’t take that away, no matter what you do.” The exhibit also shows the inmate’s detailed requests, which the organizers say are just as powerful, if not more moving to the viewer. (see bottom of this article)

The project started in 2009, within a group working to shut down the notorious Tamms Correctional Center, a super-max prison in Illinois. The inmates were strictly isolated from each other and the outside world, says Laurie Jo Reynolds, an artist and activist.

When discussing a poetry exchange with inmates, someone asked if they could send the prisoners photos. But with each photo sent, the inmate would have to give up one of their own. Reynolds asked: “Why not ask them what they want?”

Tamms was shut down in 2013, and the project was expanded to other states. The Brooklyn exhibition shows requests and photos from New York.

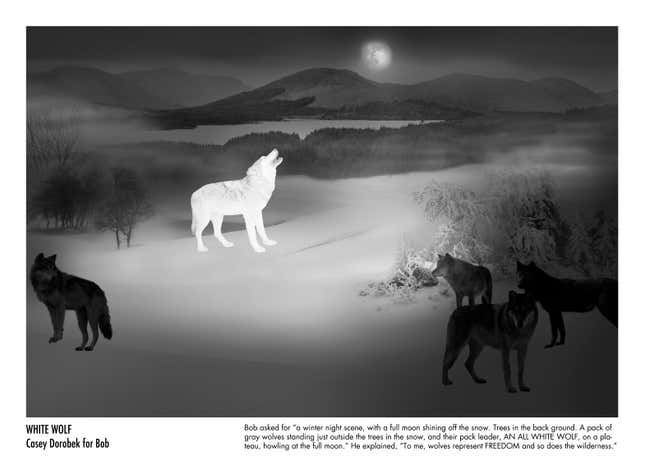

Over the years, certain categories emerged in what the inmates wanted to see in their cells. “I think those categories are useful in thinking about the experience of being in prison,” Reynolds says.

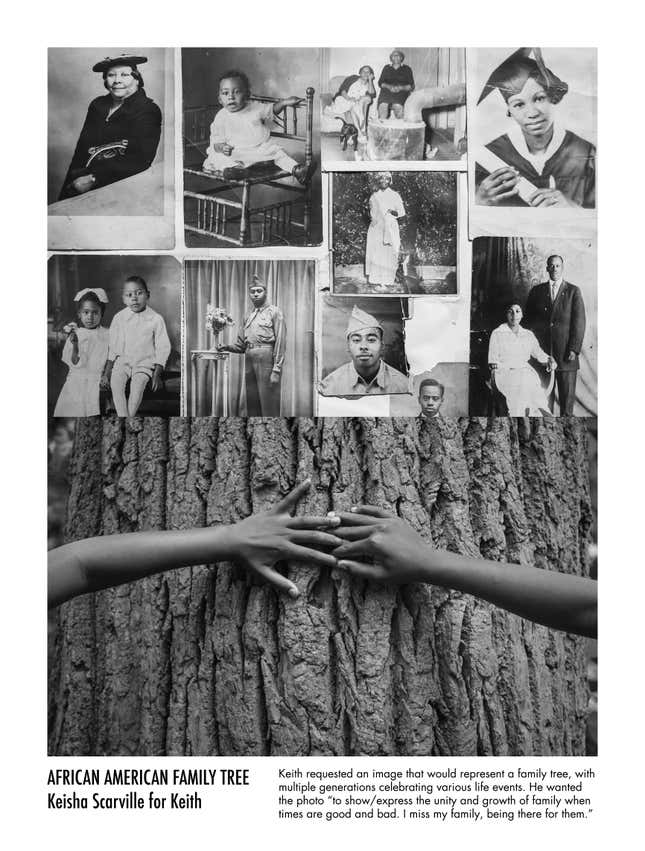

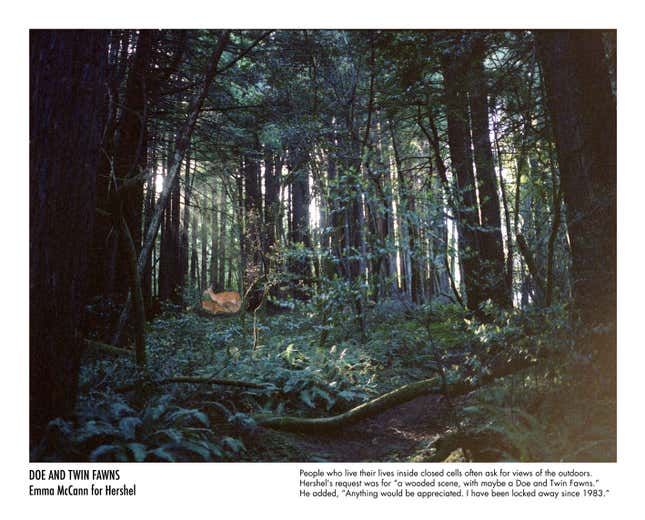

With so little exposure to the outdoors, nature is a common theme. Many inmates want glimpses of their old neighborhoods, either based on memories, or what they heard had changed. Various family pictures and religious scenes are also top on the list. Someone wanted to see Michelle Obama’s White House garden, spurred by a little snippet of what they had heard was happening in the outside world. Others wanted to see fast food.

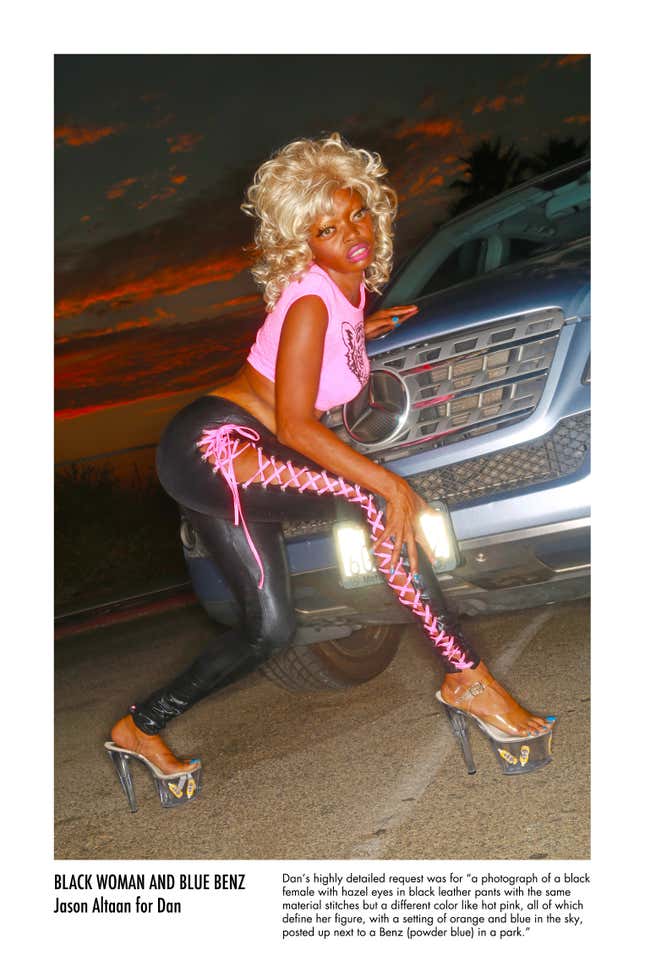

Love and romance are popular topic—as is sex. Casella says that a request to show a man with an erection would’ve been a difficult one to get past prison authorities, so they had to strategically place a pillow in the image. But Reynolds says the nature of the more erotic requests is often very romantic, comparing them to “what’s called women’s porn.”

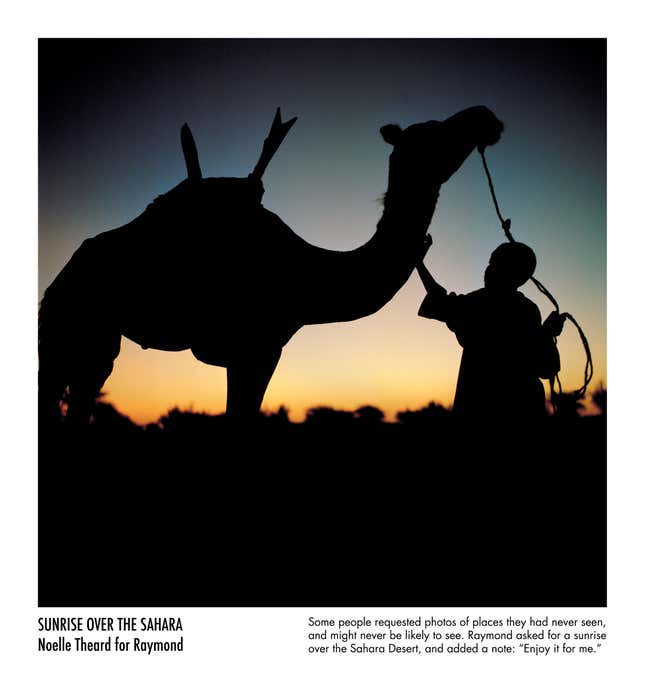

Many of these requests appear to express a longing for what it’s like to be free. At times, it’s about living vicariously, as when one prisoner asked for a photo from the Sahara desert with a note “enjoy it for me.” Sometimes “liberation” is taken very literally. Breaking shackles in one way or another (like dropping them from the Brooklyn Bridge) is a recurring motif.

“When you’re in solitary, you’re constantly trying to find ways to escape,” says Johnny Perez, a reentry advocate at the Urban Justice Center who spent a total of three years in solitary during his 15-year incarceration. “You’ll find a lot of people in solitary sleep for hours and hours, because while we’re sleeping, we’re not in that cell. We’re spiritually and psychologically elsewhere.” Pictures, he says, have a similar effect.

There are two goals for the photographs, Reynolds says. The first was to be as specific as possible when fulfilling the requests. One man, for instance, wanted his mother to be shown leaning against a Hummer in front of a mansion, with cash spread in front on the ground. Casella says that they have no qualms about using photo-editing software.

“In a sense they were giving us something to see, because they were already seeing it. The form of human connection is that we were filling something they had already seen and giving it to back to them,” Reynolds says.

And the other is to really maintain high artistic standards: “We think prisoners should have good art.”

Inmates who have gone through solitary say that any sensory reference point is crucial in a place where there is virtually no stimuli.

“It’s almost like you’re in the Twilight Zone,” says Victor Pate, an organizer for Campaign for Alternatives to Isolated Confinement (CAIC), who spent a total of two years in solitary over 15 years in prison. “It’s like it’s not real, but you know it’s real.” Anything that would connect him with the outside world would keep him from going off the “really deep, deep end.” Suicide rates in solitary confinement are high.

It’s difficult to determine how many prisoners are held in isolation in the United States. In 2015, according to Yale researchers, it was at least 67,000, both men and women. They are often held for years or decades on end, which has devastating psychological effects and has been repeatedly likened to torture by researchers, including those of the UN.

The Brooklyn exhibit comes at a critical time for New York, as a push for ending long-term solitary confinement is gaining support in the state’s legislature. Perez and other former inmates are among those staffing the exhibit, which aims to create a link between the public, and those who are, as Pate put it, “out of sight, out of mind.”

The organizers point to the requests as a particularly powerful form of making that connection.

“When you’re reading a request, you realize you’re learning about something people are already seeing and thinking about,” Reynolds says. “And so you’re drawn to thinking much more about that person, as someone directing the image.”

59 Ramon NY by Hanna Kozlowska on Scribd

[protected-iframe id=”522dc2dae68c31e9788a5f4251f599b2-39587363-75954738″ info=”https://www.scribd.com/embeds/358915081/content?start_page=1&view_mode=scroll&access_key=key-2uvHXlB7PhgKWO2K8nI8&show_recommendations=true” width=”100%” height=”600″ frameborder=”0″ class=”scribd_iframe_embed” scrolling=”no”]

33 Rafael NY by Hanna Kozlowska on Scribd

[protected-iframe id=”c8dfff25b750cd8a009b7eaebb7a5789-39587363-75954738″ info=”https://www.scribd.com/embeds/358913829/content?start_page=1&view_mode=scroll&access_key=key-K05G82NQOvZm89sXktpR&show_recommendations=true” width=”100%” height=”600″ frameborder=”0″ class=”scribd_iframe_embed” scrolling=”no”]