China is stumbling hard at acquiring the high-tech chip companies it wants so badly

US president Donald Trump yesterday (Sept. 13) vetoed a Chinese private-equity firm’s proposed $1.3 billion purchase of Lattice Semiconductor, an Oregon-based chip manufacturer.

US president Donald Trump yesterday (Sept. 13) vetoed a Chinese private-equity firm’s proposed $1.3 billion purchase of Lattice Semiconductor, an Oregon-based chip manufacturer.

The deal’s failure marks the latest instance where foreign governments have pushed back against China’s efforts to acquire technology assets in their country, as China invests heavily in hardware and software companies at home and abroad.

The semiconductor industry in particular has been a focus of China’s ambitions, as chips are the brains of nearly every electronic device. But as of 2014, China still imported 90% of its semiconductors. As a result, the country has gone on a spending spree, buying up semiconductor companies all over the world.

Many of these deals have fallen through, however, due to pressure from the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), an inter-agency branch of the Treasury that examines foreign purchases of domestic companies and assesses their potential impact on national security. While CFIUS does not “block” deals outright, it can make “recommendations” to both parties involved that the deal ought to be terminated. If necessary, CFIUS will refer cases to the president, who then holds the power to veto the deals—which is what happened with Lattice.

Lattice marks the seventh such major deal that has collapsed since mid-2015, and it’s the second to be vetoed by the US president within that period. This list shows just how badly China is failing at acquiring foreign semiconductor technology.

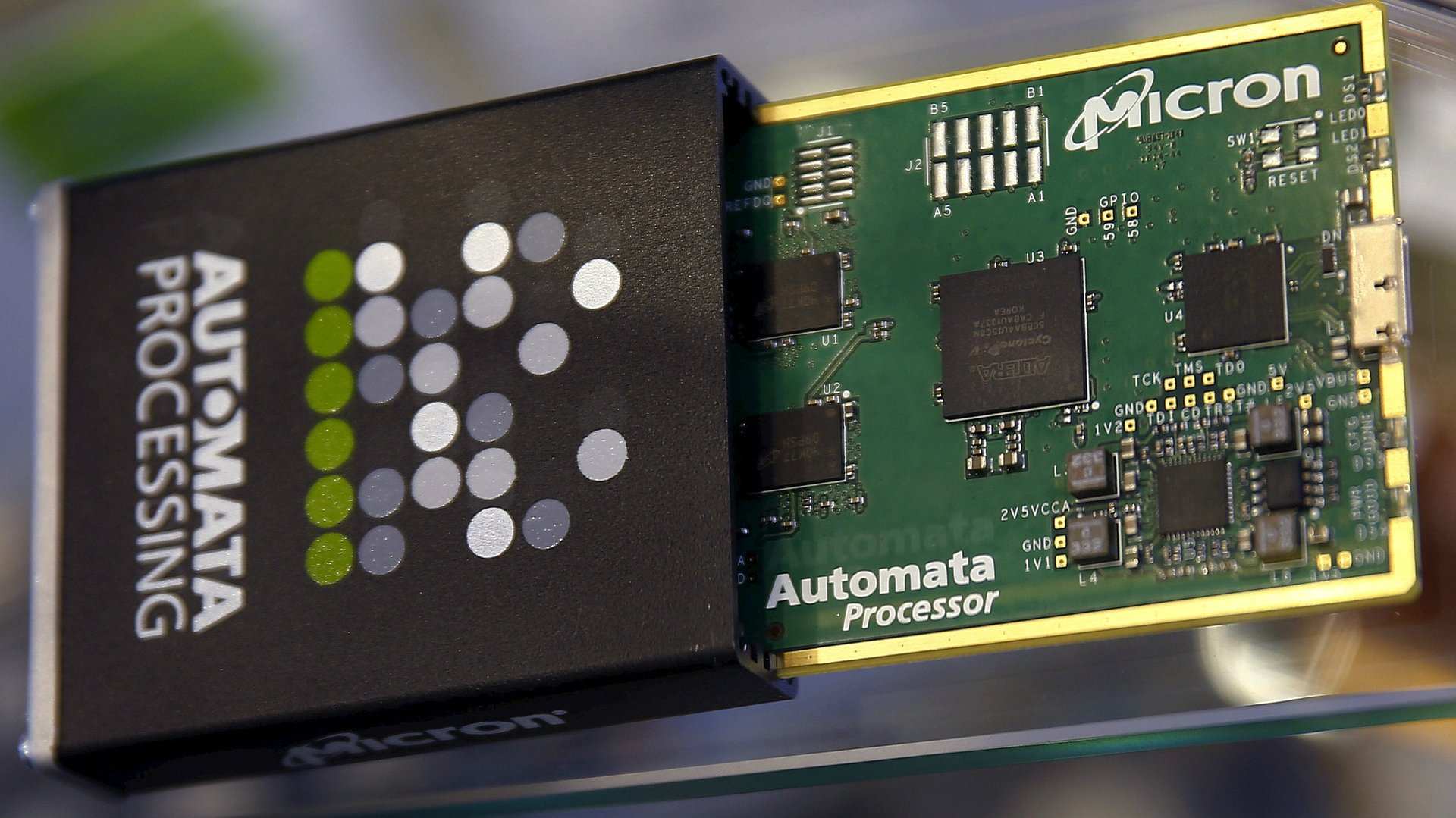

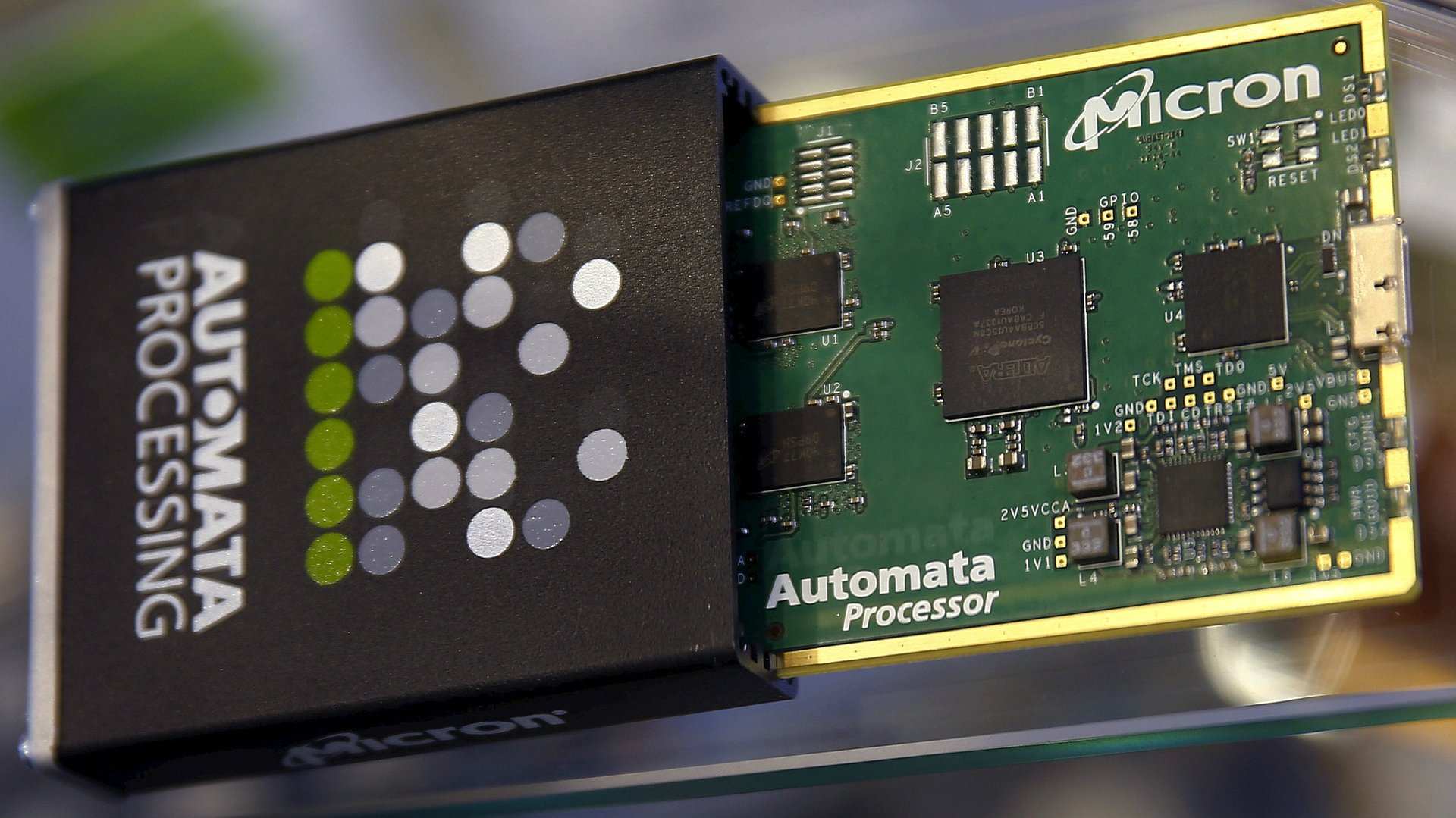

Micron

The largest attempted Chinese takeover of a US semiconductor maker began in July 2015, when media revealed that Tsinghua Unigroup, a state-affiliated Chinese chipmaker with ties to with Tsinghua University in Beijing, wanted to buy Idaho-based Micron. Tsinghua Unigroup reportedly had put up $23 billion (paywall) to purchase the company.

Micron made it clear it was cold on the deal from the get-go. Just days after Tsinghua Unigroup’s bid hit news outlets, a source at Micron told Reuters the deal was likely not possible as CFIUS would probably recommend against it. In August that year, senator Chuck Schumer, a frequent critic of China, directly called on CFIUS to formally investigate the potential acquisition.

But the deal didn’t even get that far. Despite reports that Tsinghua’s chairman travelled to the US to talk to Micron, no further details about a deal emerged until November 2016, when Tsinghua confirmed it was not in any talks with the Idaho company.

Had both sides reached an agreement, the deal would have carried historic implications for the US tech industry. Micron to this day remains the last major US-based manufacturer of DRAM flash memory, a critical component in nearly all consumer electronic devices. Its American rivals all ceded ground to competitors in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

Fairchild Semiconductor

In December 2015, state-affiliated conglomerate China Resources Holdings made an unsolicited offer to purchase Fairchild Semiconductor, one of the oldest companies in Silicon Valley. The Chinese investors proposed paying $2.5 billion for the company, equivalent to $21.70 per share, a premium over what rival bidder, US-based On Semiconductor, had offered earlier. The Chinese suitors also offered a $108 million reverse termination fee in the event that CFIUS recommended against the purchase.

Despite the markup and the guarantee, Fairchild refused the offer in February 2016, stating that the deal presented an “unacceptable level of risk” of failing should it ever reach CFIUS. It ended up being sold to On Semiconductor in September 2016.

Lumiled

In March 2015, Dutch electronics giant Philips, which is also listed in the US, announced it intended to sell an 80% stake in Lumiled, a subsidiary that manufactures LEDs (light-emitting diodes), a semiconductor, to a Chinese consortium known as GO Scale Capital for $3.3 billion. In October, however, the company stated in its latest earnings report that CFIUS had “expressed certain unforeseen concerns” towards the deal, which could ultimately kill it.

The bid was dead by January 2016. “I am very disappointed about this outcome as this was a very good deal for both Lumileds and the GO Scale Capital-led consortium,” said Philips CEO Frans van Houten. While LEDs are generally associated with lighting, according to the New York Times, CFIUS held concerns that the gallium nitride used to make the components could also be used by China’s military (paywall). Philips eventually agreed to sell Lumiled to US-based private-equity firm Apollo Global Management in December 2016, at a discounted price of $2 billion.

Western Digital

In September 2015 Tsinghua Unisplendour, owned by the same parent as Tsinghua Unigroup, announced it intended to pay $3.78 billion for a 15% stake in Western Digital, the semiconductor maker best known for its hard-disk drive business. The company told investors it did not expect the deal to be subject to a CFIUS review because the stake was non-controlling. But in February 2016 Tsinghua backed out of the deal (paywall) once it became clear that a probe was indeed forthcoming. The two companies’ relationship didn’t end there, however. In September 2016 Western Digital and Tsinghua Unisplendour announced they had formed a China-based joint venture with Tsinghua as the majority shareholder.

GCS

In March 2016, California-based, Taiwan-listed semiconductor maker GCS announced it was in talks to be purchased by Sanan Optoelectronics, a Chinese maker of LED wafers and solar cells, for $226 million. In August, GCS confirmed that the deal had fallen through due to pressure from CFIUS. The body did not state its specific objections, but they likely stemmed from GCS’s contracts with the US military. Like Western Digital, GCS opted to form a joint venture with its Chinese suitor as an alternative.

Aixtron

In May 2016 China’s Fujian Grand Chip announced it had agreed to buy Germany’s Aixtron, a maker of semiconductor manufacturing equipment, for $752 million. In November, Aixtron announced that CFIUS told both parties there were “unresolved U.S. national security concerns regarding the proposed transaction.” Rather than kill the deal, Aixtron and Fujian Grand Chip said they would appeal the recommendation directly to president Barack Obama—who sided with CFIUS. The White House said that there was “credible evidence” that Fujian Grand Chip “might take action that threatens to impair the national security of the United States.” The process—a CFIUS warning, an appeal to the president, and then a veto–was the same process that led to the collapse of the Lattice deal.