This is why we can’t have autonomous things.

Inga Beale, CEO of Lloyds, says the insurance giant has been ready to insure autonomous vehicles such as self-flying planes for two decades. Regulators have proven unwilling to green-light the technology, while the public remains wary of completely handing over the cockpit to computers.

“We’re all set [to issue] insurance for autonomous planes,” Beale told Quartz. “The regulators just haven’t pressed the button even though the technology has been around for 20 years.”

Civil aviation agencies around the world have done an extraordinary job of keeping people safe. The International Air Transport Association reported no passenger jetliner accident fatalities anywhere in the world, excluding criminal acts, in 2015. But the technology to make the skies even safer by eliminating human error, and handing the keys completely over to computers, has been around for a long, long time. It’s just not being used.

Computers are already behind the stick for most of a commercial flight. During a 2.5 hour domestic trip, 95% of the work is handled by autopilots and flight-management systems, reports The Atlantic (pilots only handle takeoff and landing, although computers can do this job just as well). ”Fly-by-wire” systems, where electronics manage the plane’s controls rather than the pilot’s physical movements, have taken over most functions once performed by humans.

That’s been the case for case for decades. The US Air Force started landing autonomous F-18s on aircraft carriers as early as 1994. “With respect to a commercial airplane, there is no doubt in our minds that we can solve the problem of autonomous flight,” John Tracy, Boeing’s chief technology officer, said in 2015. ”It’s a question of certification procedures, regulatory requirements and, even more significantly, public perception.”

It’s not that there aren’t things that might flummox an autopilot. Humans have pulled off incredible feats such as Captain Chesley Sullenberger’s landing of a crippled Airbus A320 in the Hudson River in 2009, and while it’s possible a remote connection might been able to bring the plane down safely, replicating the “feel” of an aircraft for remote pilots in an emergency has yet to be tested. Hacking airliners’ system also remains a concern.

But most concerns overlook the fact that, overall, autonomy has made vehicles safer. It’s hard to resist the image of terrorists in Die Hard 2 commandeering an airplane’s autopilot to slam it into the ground, despite its implausibility. A 2014 survey (pdf) found that Americans and Indians were extremely uncomfortable with either autonomous or remotely-controlled commercial airlines compared to those with pilots in the cockpit.

Today, the the US Federal Aviation Administration still requires all commercial flights to have certified pilots in the cockpit. The only two unmanned aircraft systems that have been FAA certified, Boeing’s ScanEagle and Aerovironment’s Puma, fly in the Arctic—remote applications with no risk of commercial incident. The FAA has made some moves towards embracing more autonomous planes—the first large, fixed-wing unmanned aircraft to fly at an FAA-approved site was tested in 2015, reports CNN—but no approvals seem imminent.

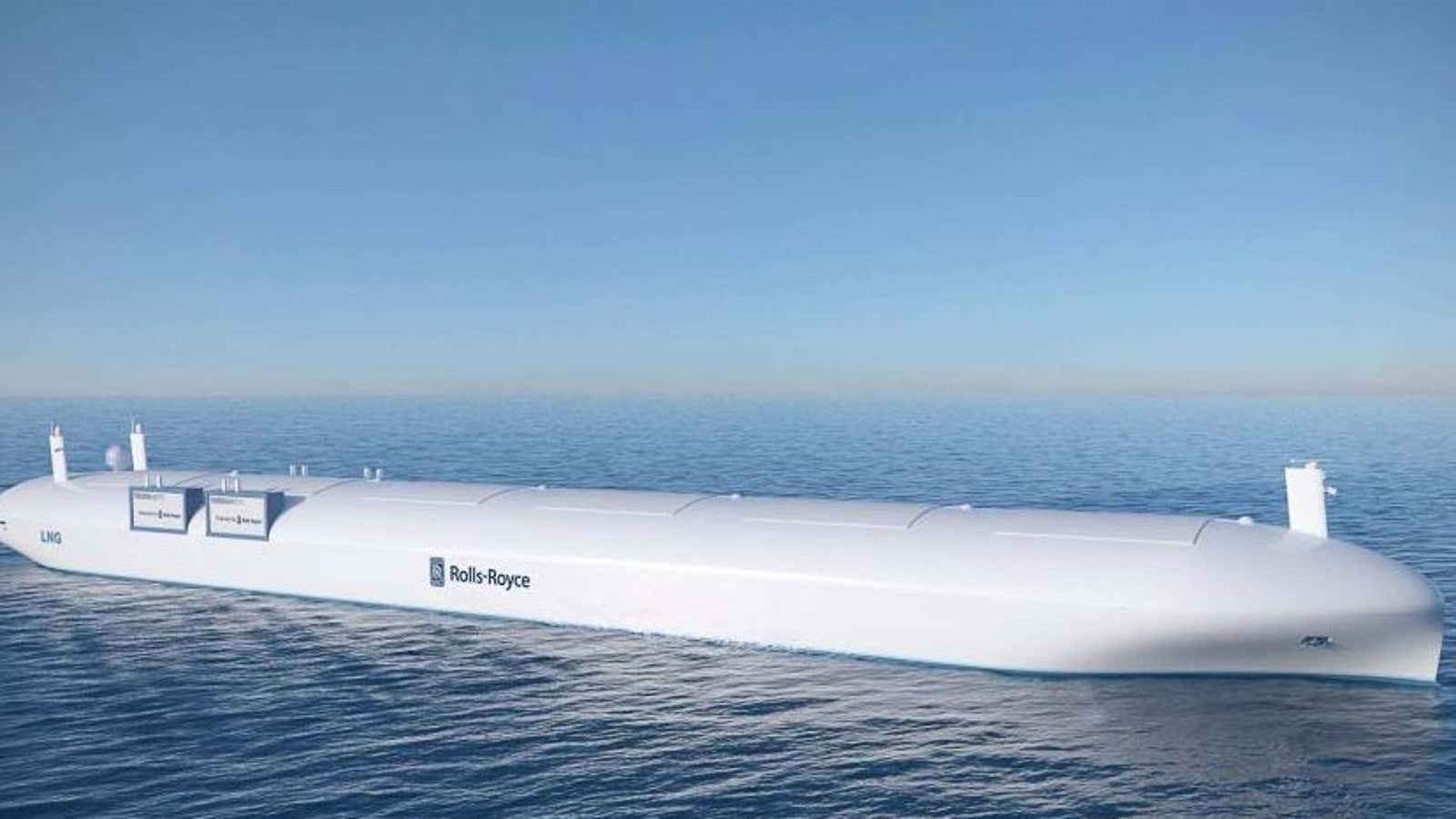

Next up is oceanic shipping. “Drone ships,” or self-driving ocean vessels, are already in use by the military. Rolls Royce among others are planning for self-driving ships to move freight across the oceans. But when it comes to setting sail, it’s not the way that is lacking, it’s the will.

“Autonomous shipping will be here in two years,” said Beale. “But I doubt it will implemented. You won’t have regulation and international law agreeing it will be safe. Often the technology is way ahead of the ability of our society to accept it.”