The future of making neighborhoods safer might lie in simply making them look safer. That’s what researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Austrian Institute of Technology concluded from results gathered on this website, which allows visitors to rate pictures of urban areas like they’re Tinder headshots:

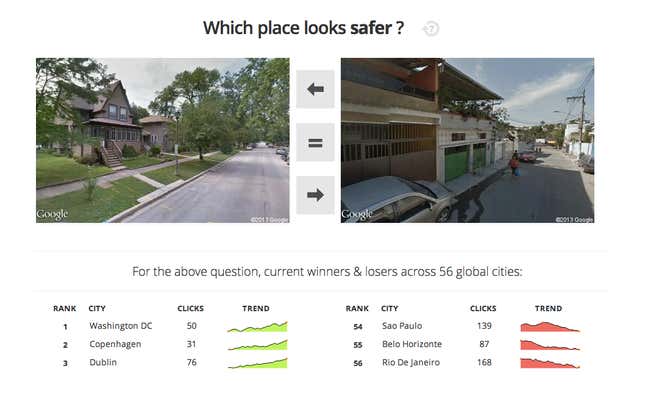

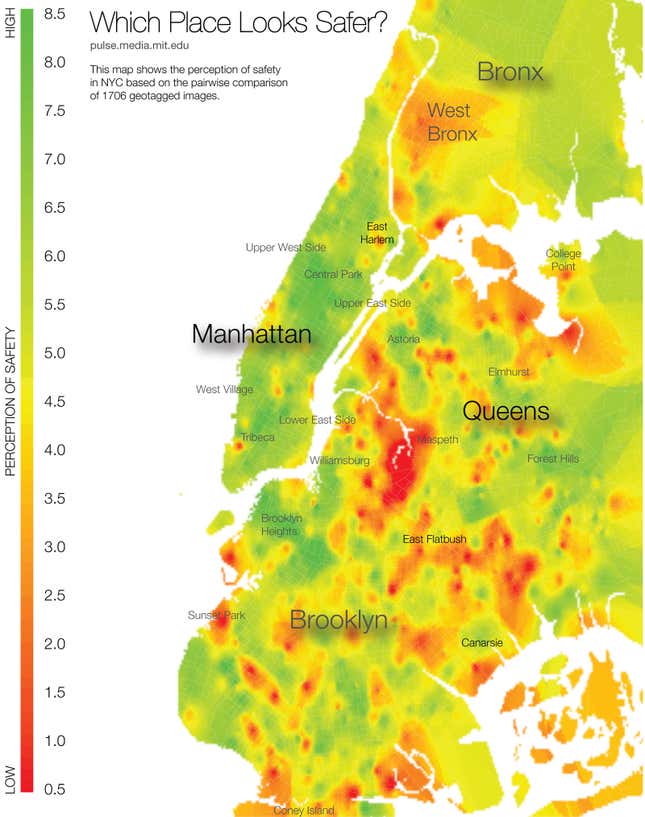

Initially, the tool covered only New York and Boston in the United States, and Linz and Salzburg in Austria. The researchers directed nearly 8,000 online participants from 91 countries to rate pairs of geotagged photos in terms of which looked “safer” and “more upper-class.”

It turned out to be an important distinction. Researchers also found that the difference in the gap between highest perceived neighborhoods and the lowest was much wider in New York and Boston than in Linz and Salzburg.

Most importantly, though, the researchers found that how safe a neighborhood looks correlates with its crime rate, even when researchers adjusted for income. For instance, some “upper-class” neighborhoods were also rated “unsafe”—and they had high crime rates. In other words, a neighborhood that’s perceived as being both wealthy and neglected was even more of a target for crime than a poor one.

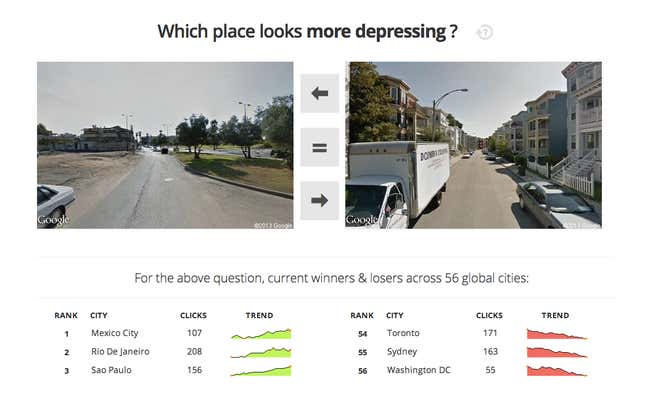

Researchers since expanded the project to cover 56 cities, as well as including additional categories (e.g. “depressing,” “lively,” and “boring”). It turns out that Rio de Janeiro is the “most depressing” city, while Helsinki is everybody’s happy place.

Though the study is the first to quantify it on a large scale, the idea that perceptions of our surroundings influence behavior isn’t new. Commonly known as the Broken Windows Theory, or BWT, the notion was introduced in a 1982 edition of The Atlantic Monthly. If a window stays broken for long enough, goes the argument, people will feel less hesitation about breaking another. Or if too much litter and uncollected garbage accumulates on a street, you’ll reach a point where no one feels bad about throwing their trash onto the heap anymore.

But it’s not just windows and trash; when people observe that no one prevents crime in an area, they’re more likely to break the law. Put another way, the perception of disorder and violence in a neighborhood causes a feedback loop of more disorder and violence. This is the guiding philosophy behind zero-tolerance policing and the implementation of school uniforms: If you discourage the tiny breaks from order, like loitering on stoops and wearing untucked shirts, you might decrease major problems as well.

This theory has been hard to prove, though. After all, the relationship between a street looking dingy and rampant vandalism is kind of a chicken-egg one. It’s also difficult to decide exactly what makes a street, neighborhood, or entire city feel disorderly and unsafe.

The significance of the new tool is that it makes it easier to quantify these perceptions, and to draw correlations from them. Those data should in theory encourage urban planners and city officials to act on the results, which could have a big impact on public works and crime prevention policies. “One of the things that would be the most interesting in the long run,” head researcher César Hidalgo said, “is to overlay these maps with expenditures of government, narrowly defined by the things that affect how places look, such as repaving roads, building parks, or putting cables underground.”

If that exercise showed that public safety is lowest where visible neglect is ranked highest, it would follow that cities should invest in beautifying these neighborhoods as much as they invest in policing them. The theory needs a lot more research before it holds any water, but Hidalgo and his team have created a vital tool for getting there.