“Life is too short to be living somebody else’s dream.” That quote from Hugh Hefner—along with a golden-hued image of the man in his prime, chomping on a pipe—was splashed upon the homepage of Playboy’s website last evening in the wake of the news that Hefner, the magazine’s founder, died at age 91. The slogan sums up not only Hefner’s legacy, but the distinctly American myth he embodied—for better and for worse.

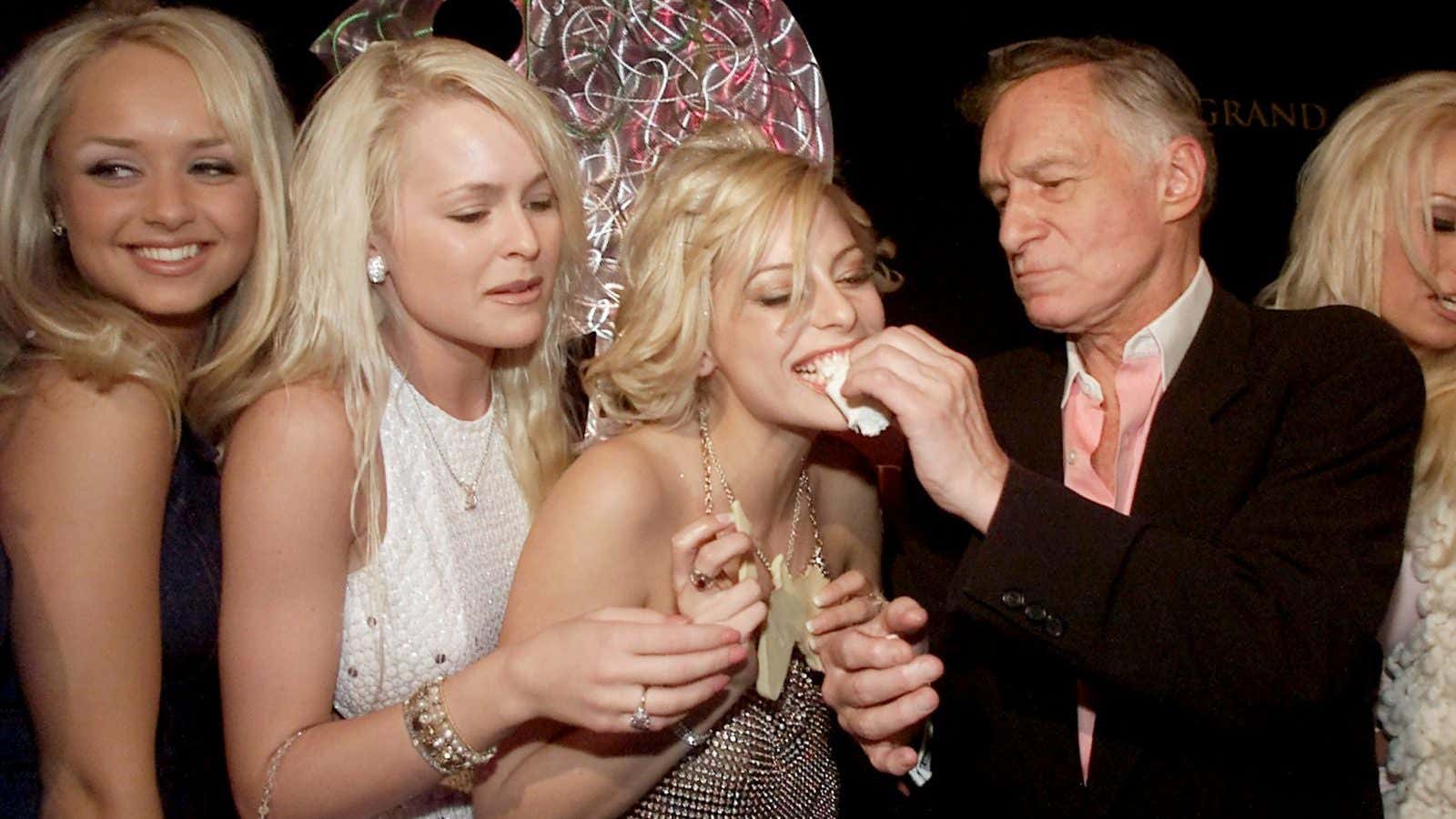

The place Hefner holds in the public consciousness is inextricably linked with the commercialization of sex and the sexual revolution. Playboy’s nude centerfolds and attractive young women in tight bunny costumes were a defining feature of the post-World War II era, and Hefner famously dated a string of young blonde women into his octogenarian years.

But sex, for all it prominence, was never exactly the core of Playboy—a publication for which, full disclosure, I am a freelance writer. Rather, Hefner was selling a particular vision of America in the latter half of the 20th century. The child of middle-class teachers, Hefner transformed himself, through hard work, vision, and careful, conspicuous consumption, into a wealthy man and a cultural icon. Playboy’s premise was that Hefner had remade himself, and you could too—presuming that “you” were a man.

The opportunity for reinvention had to do with wealth and sex, but it was also about cultural sophistication. Hefner’s image was a combination of Horatio Alger and Lord Byron—a self-made workaholic decadent aesthete. Playboy wasn’t just for ogling women; it was a guidebook to social climbing as an act of sensuality. Hefner was in the business of teaching readers to better themselves. People joke about reading Playboy for the articles, but the articles—an iconic interview by Alex Haley with Miles Davis in 1962, the serialization of Fahrenheit 451 in 1953—were central to its mission. The Playboy gentleman reader appreciated the finest things in life, and as a result the finest things in life (in theory) came to them.

At its best, Playboy, and Hefner, showed how the American pursuit of happiness and the American commitment to equality could coexist with one another. Hefner’s bootstrap hedonism was consciously democratic. In the old mouldering capitals of Europe, you had to be born rich to be a playboy. But in Hefner’s bustling new America, anyone could be a suave dilettante.

Hefner’s idealistic cosmopolitanism led him, inevitably, to champion broad free speech rights. But it also put him on the side of the Civil Rights movement. The television jazz and variety show Playboy Penthouse, which ran from 1959-1961 and was hosted by Hefner, featured numerous black performers. As a result, it had trouble breaking into Southern markets. When club franchise owners in the South refused to let black people into Playboy clubs, Hefner purchased the licenses from them at considerable cost, and integrated the clubs himself. Hefner also promoted the careers of important black comedians like Dick Gregory, who praised Hefner’s “life long battle for racial equality.” And he was committed to gay rights; Playboy published a pro-gay science-fiction piece in 1955, at a time when the United States was virulently homophobic.

The Playboy man was forward-looking and daring. He was committed to the inherently contradictory American notion that every man, whatever their race or sexuality, should have the opportunity to be elite. Women, for their part, were an aspect of the good life. But the good life—and the magazine—wasn’t designed for them.

Women in the pages of Playboy were sex objects, obviously. But more than that, they were status objects. Hefner’s dream of success involved reading the best literature, drinking the best wine, listening to the best music, and sleeping with the best—read, most conventionally attractive—women. As Helen Rosner wrote on Twitter, “surrounding mind-blowingly excellent articles with pictures of nude women is a good way to make it clear that you don’t expect women to read the articles.” The path to success and status and sophistication depended in part on appreciating and obtaining women, which meant that women were excluded from the vision of attaining those things for themselves.

Hefner also supported birth control and abortion rights, and greater sexual openness has had benefits for women as well as men. Dianna E. Anderson, a writer who grew up in Evangelical purity culture, for example, told me in an interview for the website that Playboy is “a symbol of the sexual revolution and of sexualization.” That symbol can be meaningful for women who are too often told by conservatives that they aren’t allowed to be sexual beings.

That said, Playboy’s imagery of women as always sexually willing can be stifling and dangerous in its own way. Women from Gloria Steinem to Holly Madison have testified that the environment in the Playboy clubs and Playboy mansion could be hostile and abusive. An ethos that says successful men are entitled to beautiful women will necessarily encourage some men to ignore women’s consent. Bill Cosby, Hefner’s close friend for years, has been accused of assaulting Playboy bunnies and women in the Playboy mansion.

The American dream of remaking oneself happier, sexier, more cultured and more successful can appeal to both women and men. Hefner was at his best when he championed the pursuit of happiness for the stigmatized and marginalized, as well as for the powerful. But as Playboy showed, when you define success as social climbing, you are bound to climb over someone. Hefner believed that the good life should be open to all. But he defined the good life for his readers, in no small part, as the ability to use women for one’s own pleasure. There is no more American contradiction.