The man known as Dr. Seuss remains one of our most well-known and celebrated children’s book authors. But Seuss, whose real name was Theodor Geisel, wasn’t always sensitive when it came to social issues. Some of his children’s books contain racist depictions of characters, as did cartoons he drew of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Seuss presents a complicated case. Some of his work contains offensive racial stereotypes, while books like Horton Hears a Who! and The Sneetches reflect strongly anti-racist themes, as Philip Nel, a professor of children’s literature at Kansas State University, told USA Today. Seuss also seems to have understood the importance of breaking away from female stereotyping—at least judging from what may be his most obscure and least successful book, The Seven Lady Godivas.

The 1939 book, Seuss explains in its foreword, is an attempt to set the record straight on the legend of Lady Godiva. “History has treated no name so shabbily” as it has hers, he declares.

According to the legend, Lady Godiva was the wife of a nobleman who rode a horse naked in order to convince her husband to reduce taxation on his tenants. The town’s population was forbidden from looking at her. But a voyeur, or “Peeping Tom,” broke the rule, and was blinded as punishment.

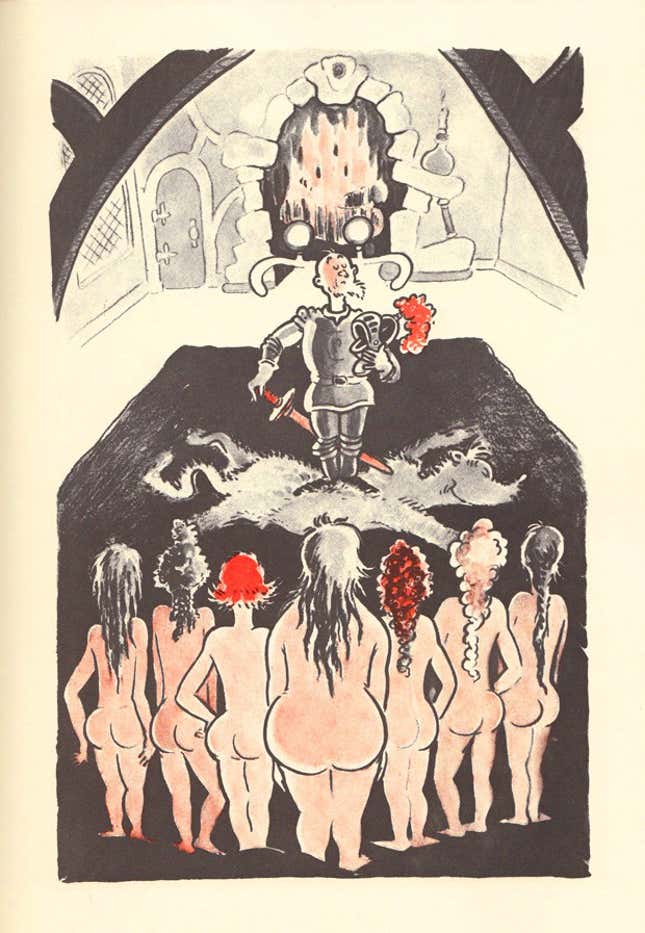

Because of this voyeur, and the implicit suggestion that Godiva’s nudity was sexual in nature, the image of Lady Godiva has long been associated with mockery and innuendo. But Seuss’s story declares that there were not one but seven Lady Godivas, and that “their nakedness actually was not a thing of shame.”

Peeping Tom, too, gets vindicated: He wasn’t a voyeur, but a man whose family name was Peeping—he had six brothers, and all seven siblings were in love with the Ladies.

And how could they not be! The book’s illustrations are a joyful portrait of body positivity. The ladies come in all shapes and sizes, and proudly go about their adventure without so much as a mention of how and why they are naked. They just are—so what.

Perhaps the best part about the book is that it lays out its politics from the get-go. As in many classic tales, it begins with a king summoning his daughters before him. “For a long silent moment he regarded them proudly,” reads the story, “for the seven daughters of Lord Godiva had brains.”

It might not seem much, but how many fables—in 1939, or today—begin with women being first and foremost complimented for their brains? Not only that: The young ladies stand in front of their father naked as they they were born, and that’s not an issue. Their bodies are neither complimented nor criticized. Their nudity is matter of fact, as are the ladies themselves. “Nowhere,” the king thinks, “could there be a group of young ladies that wasted less time upon frivol and froth. No fluffy-duff primping, no feather, no fuss.”

That’s utterly important because, in this book, there are no princes going on an adventure, at the end of which they will marry their princesses. Instead, the ladies vow that they will not marry until they have satisfied their thirst for scientific discovery.

The king dies while riding a horse, a mysterious creature at the time. When they find out, Seuss writes, the seven Godivas “stiffened their shoulder and faced the facts. […] Horses must be studied and charted, made safe for posterity.” They decide to put off marriage until they have “brought to the light of the world some new and worthy Horse Truth, of benefit to man.”

And so they set out seeking Horse Truths—a fact about horses that then becomes a proverb, such as that they should not be looked in the mouth. The women learn about horses through adventures and, most importantly, “research” or—as they themselves define it, “the concentrated examination and correlation of the multitudinous phenomena co-existent in some specific field of activity.”

Meanwhile, their beaus worry about “not getting any younger” and wait for them while making plans for marriage. Eventually, the men’s patience is rewarded, and the heroines make it back home. It’s a happy role-reversal of an ending—a fine twist for this “story of love and scientific achievement.”

![“[…] their nakedness actually was not a thing of shame.”](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fill,h_900,q_60,w_1600/663a936a0fd47a68bef7a2bce1c6f2cc.jpg)